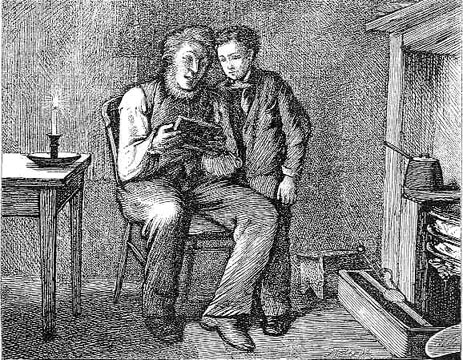

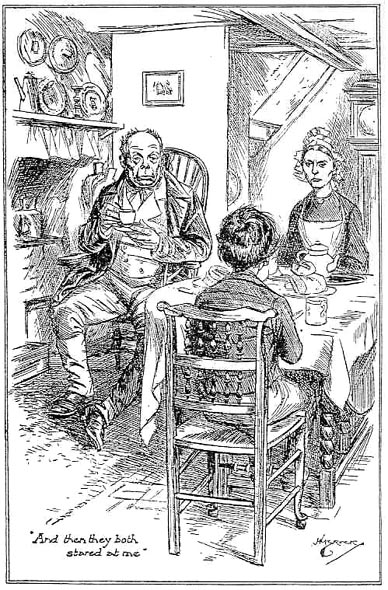

"Why, here's a J," said Joe, "and a O equal to anythink!" by F. A. Fraser (1876), in Charles Dickens's Great Expectations, Chapman & Hall. British Household Edition, for Chapter VII. 10.8 x 13.7 cm (4 ¼ by 5 ⅜ inches), framed. Running head: "Touching Joe's Education" (21). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Pip Teaching Joe to Read by the Fireside

One night I was sitting in the chimney corner with my slate, expending great efforts on the production of a letter to Joe. I think it must have been a full year after our hunt upon the marshes, for it was a long time after, and it was winter and a hard frost. With an alphabet on the hearth at my feet for reference, I contrived in an hour or two to print and smear this epistle: —

“MI DEER JO i OPE U R KRWITE WELL i OPE i SHAL SON B HABELL 4 2 TEEDGE U JO AN THEN WE SHORL B SO GLODD AN WEN i M PRENGTD 2 U JO WOT LARX AN BLEVE ME INF XN PIP.”

There was no indispensable necessity for my communicating with Joe by letter, inasmuch as he sat beside me and we were alone. But I delivered this written communication (slate and all) with my own hand, and Joe received it as a miracle of erudition.

“I say, Pip, old chap!” cried Joe, opening his blue eyes wide, “what a scholar you are! An’t you?”

“I should like to be,” said I, glancing at the slate as he held it; with a misgiving that the writing was rather hilly.

“Why, here’s a J,” said Joe, “and a O equal to anythink! Here’s a J and a O, Pip, and a J-O, Joe.” [Chapter VII, 20]

Commentary: Pip's Nascent Literacy and the Narrative Voice

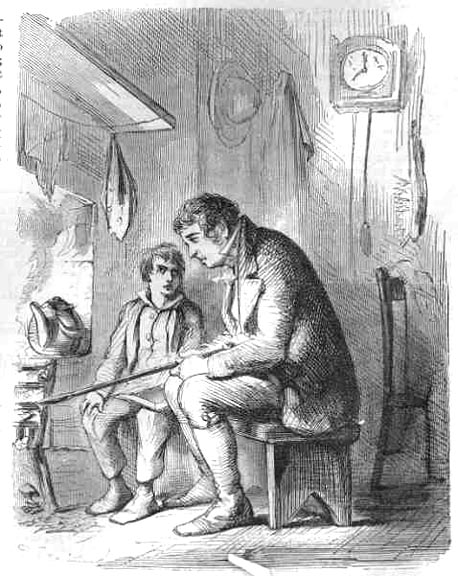

Then Joe began to hammer and clink, hammer and clink by John Mclenan in the Haper's Weekly edition (8 December 1860) depicts Joe as a respectable, middle-class artisan.

F. A. Fraser draws the reader's attention in this illustration for Chapter 7 to the gap between the sophisticated narrative voice (the mature Pip as he reflects upon crucial events from his childhood on the Kent marshes) and the child from a barely literate, lower-middle-class home. As the tet suggests, neither Joe Gargery nor his termagant wife, Mrs. Joe could possibly have served as models for the sophisticated usage and reflective observations that one finds everywhere in these opening chapters. The reader wonders as he or she peruses the plate and the accompanying letterpress how an artisan's adopted son, the product of the village dame school, could possibly construct so complex and subtle a narrative.

Fraser emphasizes the respectable, middle-class nature of the village blacksmith and his tidily dressed brother-in-law looking over his shoulder in this almost sacred moment in which adult and child reverently study a text. The scene is evening, as the candle on the table suggests, and the pair are attempting to advance their literacy by the light of the taper and the firelight in this charming scene domestic of domestic intimacy.

Relevant Early Scenes from Other Editions (1860-1910)

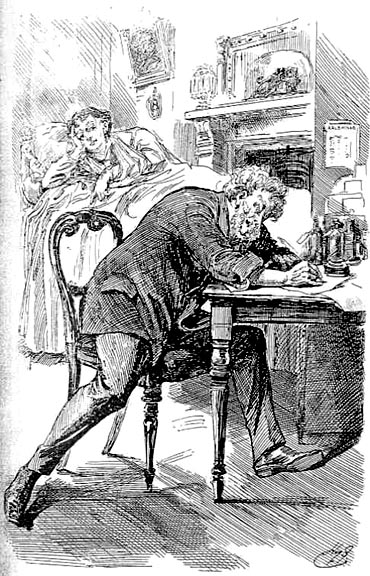

Left: Joe and Mrs. Gargery (1867), from the Diamond Edition by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Centre: In the first American serialisation, periodical illustrator John McLenan emphasizes the close relationship of the child-like Joe and his brother-in-law, fellow sufferers of Mrs. Joe's domestic tyranny in "At such times as your sister is on the ram-page, Pip." (15 December 1860). Right: Harry Furniss's 1910 lithographic depiction of Joe's writing his own note home in Ch. 57 as a result of Pip's earlier sharing his dame school education: Joe indites a note to Biddy, in the Charles Dickens Library Edition, Vol. 14.

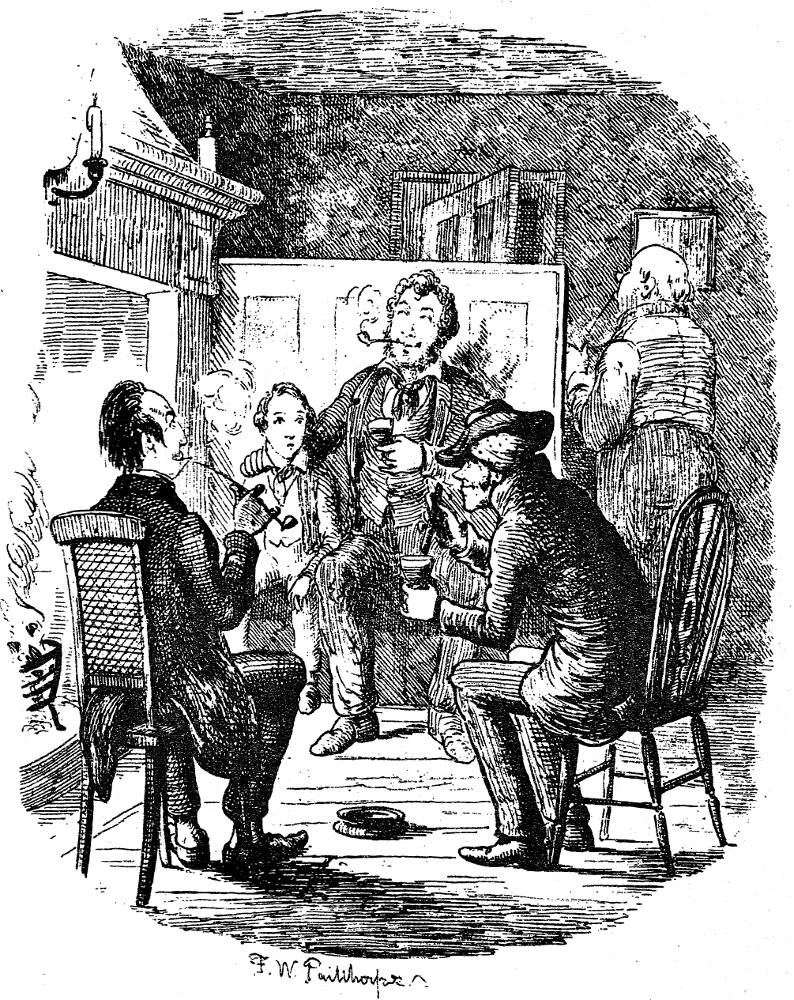

Left: F. W. Pailthorpe sets the working-class scene at the local public house that implies Pip's common origins and tastes: A Stranger at the Three Jolly Bargemen (1900). Right: H. M. Brock establishes the domestic circumstances of Pip's childhood: "And they both stared at me." (1901).

Other Artists’ Illustrations for Dickens's Great Expectations

- Edward Ardizzone (2 plates selected)

- H. M. Brock (8 lithographs)

- J. Clayton Clarke ("Kyd") (2 lithographs from watercolours)

- Felix O. C. Darley (2 plates)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (8 wood engravings)

- Marcus Stone (8 wood engravings)

- John McLenan (40 wood engravings)

- Harry Furniss (28 plates)

- Charles Green (10 lithographs)

- Frederic W. Pailthorpe (12 lithographs)

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. "The Illustrations for Great Expectations in Harper's Weekly (1860-61) and in the Illustrated Library Edition (1862) — 'Reading by the Light of Illustration'." Dickens Studies Annual, Vol. 40 (2009): 113-169.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Illustrated by John McLenan. [The First American Edition]. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, Vols. IV: 740 through V: 495 (24 November 1860-3 August 1861).

______. ("Boz."). Great Expectations. With thirty-four illustrations from original designs by John McLenan. Philadelphia: T. B. Peterson (by agreement with Harper & Bros., New York), 1861.

______. Great Expectations. Illustrated by Marcus Stone. The Illustrated Library Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1862. Rpt. in The Nonesuch Dickens, Great Expectations and Hard Times. London: Nonesuch, 1937; Overlook and Worth Presses, 2005.

______. A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

______. Great Expectations. Volume 6 of the Household Edition. Illustrated by F. A. Fraser. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876.

______. Great Expectations. The Gadshill Edition. Illustrated by Charles Green. London: Chapman and Hall, 1898.

______. Great Expectations. The Grande Luxe Edition, ed. Richard Garnett. Illustrated by Clayton J. Clarke ('Kyd'). London: Merrill and Baker, 1900.

______. Great Expectations. "With 28 Original Plates by Harry Furniss." Volume 14 of the Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Created 28 December 2004 Last modified 17 August 2021