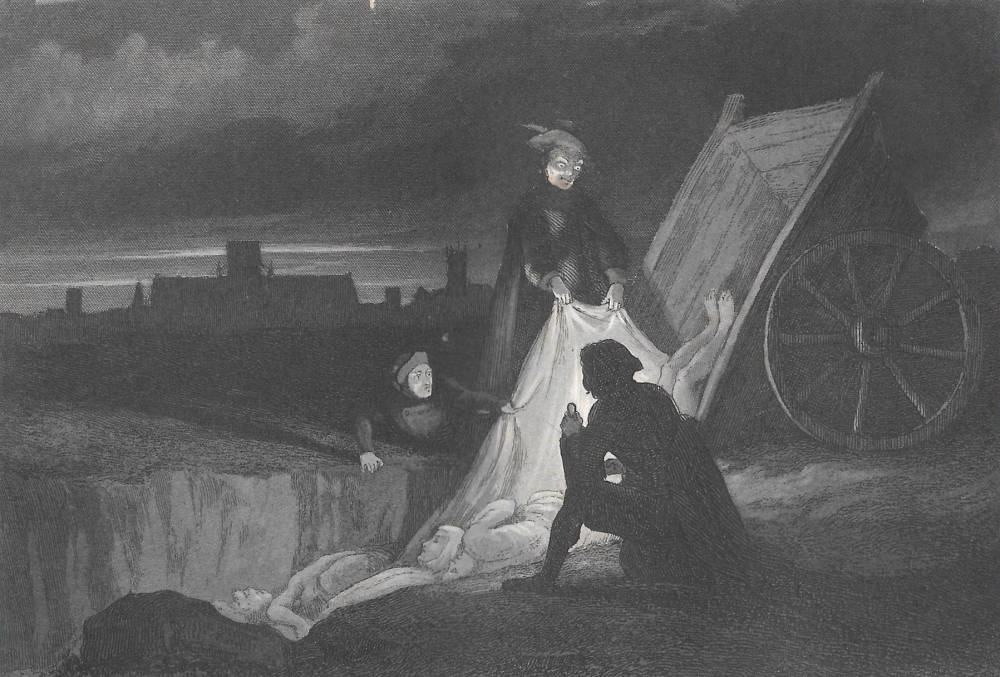

The Plague Pit. Artist: John Franklin. Drawn and engraved by Franklin, 1841, reprinted 1847. Steel-plate etching, 3 ¾ x 5 ½ inches. An illustration for W. H. Ainsworth’s historical romance, Old St. Paul's: A Tale of the Plague and the Fire (London: Parry, Blenkharn & Co., 1847): facing p. 207 in Book the Third, "June 1665," Chapter IV, "The Plague-Pit."

Scanned image and caption by Simon Cooke. You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.it

Passage Illustrated

Long after the sun had set, the sky was stained with crimson, and the grey walls of the city were tinged with rosy radiance. The heat was intense, and Leonard, to cool himself, sat down in the thick grass—for, though the crops were ready for the scythe, no mowers could be found—and, gazing upwards, strove to mount in spirit from the tainted earth towards heaven. After a while he arose, and proceeded towards the plague-pit. The grass was trampled down near it, and there were marks of frequent cart-wheels upon the sod. Great heaps of soil, thrown out of the excavation, lay on either side. Holding a handkerchief steeped in vinegar to his face, Leonard ventured to the brink of the pit. But even this precaution could not counteract the horrible effluvia arising from it. It was more than half filled with dead bodies; and through the putrid and heaving mass many disjointed limbs and ghastly faces could be discerned, the long hair of women and the tiny arms of children appearing on the surface. It was a horrible sight — so horrible, that it possessed a fascination peculiar to itself, and, in spite of his loathing, Leonard lingered to gaze at it. Strange and fantastic thoughts possessed him. He fancied that the legs and arms moved—that the eyes of some of the corpses opened and glared at him — and that the whole rotting mass was endowed with animation. So appalled was he by this idea that he turned away, and at that moment beheld a vehicle approaching. It was the dead-cart, charged with a heavy load to increase the already redundant heap.

The same inexplicable and irresistible feelings of curiosity that induced Leonard to continue gazing upon the loathly objects in the pit, now prompted him to stay and see what would ensue. Two persons were with the cart, and one of them, to Leonard's infinite surprise and disgust, proved to be Chowles. He had no time, however, for the expression of any sentiment, for the cart halted at a little distance from him, when its conductors, turning it round, backed it towards the edge of the pit. The horse was then taken out, and Chowles calling to Leonard, the latter involuntarily knelt down to guide its descent, while the other assistant, who had proceeded to the further side of the chasm, threw the light of a lantern full upon the grisly load, which was thus shot into the gulf below. [Book the Third, "June 1665," Chapter IV, "The Plague-Pit," pp. 200-201.

Commentary

Franklin’s design is a powerful (and accurate) representation of the primary Plague Pit in which thousands of victims were buried without ceremony. The artist stresses the horror of a moment when the dead are tipped into the ground. The central figure standing over the bodies is picked out in grotesque chiaroscuro, his face mask-like in the manner of Goya while also eerily prefiguring the expressionistic distortions of Modernist artists such as James Ensor and Emile Noldë.

The sense of strangeness and aberration is also inscribed in the vertiginous and unstable composition – with the cart tipping a diagonal from right to left – and even in the flattened shape of the cart-wheel. In the Plague, Franklin shows, nothing is ‘normal’; in Hamlet’s strange terms, it is quite literally ‘out of joint’.

The illustration, a steel-plate engraving, is a fine example of etching in the manner of a mezzotint, and may have been an influence on Phiz’s later designs for Dickens. Franklin drew and ‘bit’ his own plates, a talent he failed to develop in his later commissions.

Related Material: Phiz's Frontispiece and Title-page Vignette (1842)

- Drink the Plague! Drink the Plague: frontispiece

- The Dead Cart: title-page & vignette

Reference

Ainsworth, William Harrison. Old Saint Paul's: A Tale of the Plague and the Fire. London: Parry, Blenkharn & Co., 1847. This was a one-volume reprint of the three-decker published by Hugh Cunningham in 1841. Routledge re-issued the single volume with the Franklin illustrations prefaced by two additional engravings by Hablot Knight Brown.

Last modified 9 August 2018