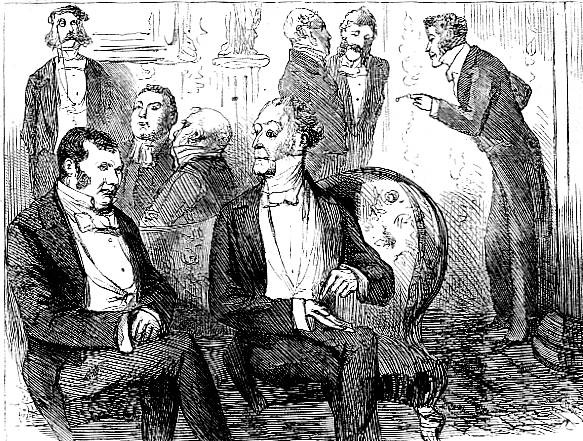

"The Merdle Party," the twelfth full-page illustration for the volume by Sol Eytinge, Jr. 1871. 7.4 cm high by 9.9 cm wide. The Diamond Edition of Dickens's Little Dorrit (Boston: James R. Osgood, 1871), facing page 323. Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

In the twelfth character study to complement Dickens's narrative, Eytinge's "The Merdle Party," Eytinge does not realise the sophisticated but supercilious Mrs. Merdle, but rather focuses on the figure and political relationships of her husband, the financier. According to biographer Peter Ackroyd and The Dickens Index, Dickens had modelled the character of Merdle (undoubtedly a pun on the French "merde" ["excrement"] and "hurdle") on two notable mid-century financial frauds: John Sadleir and George Hudson. Dickens, a self-made man whose greatest secret and shame was his months spent as a bottle-labeller in Warren's Blacking at Hungerford Stairs, perhaps identified himself with the early spectacular successes of Sadleir (born in Ireland in 1813, and therefore very much Dickens's contemporary), who committed suicide near that familiar Dickensian haunt, Jack Straw's Castle, a quaint tavern on London's Hampstead Heath, by drinking prussic acid, after the insolvency of the Tipperary Bank in 1856 caused by Sadleir's £288,000 overdraft resulting from bad investments and massive overspeculation, and to a certain extent with the entrepreneurial Hudson (1800-1871), "The Railway King," whom the writer had met the year before Sadleir arrived in London through a mutual acquaintance, Joseph Paxton (1813-1865, the architect of the Great Exhibition's Crystal Palace), when founding The Daily News in the autumn of 1845, some four years prior to the collapse of George Hudson's empire with the exposure of massive fraud in his Eastern Railway. Much of the capital behind the newspaper came from railway speculation, strengthening Dickens's identifying his own fortunes with those of Hudson. Like Dickens, although some dozen years older, Hudson had comparatively modest origins (he was the fifth son of a Yorkshire farmer) and little formal education. Unlike Sadleir, Hudson did not commit suicide, choosing instead to flee to the Continent after his failure to be elected to the House of Commons in 1859. The connection between the character of Merdle and these celebrated masters of fiscal mismanagement must have been readily in apparent when Little Dorrit was first published in 1855-57, but by the time of the publication of the Diamond Edition in 1871 the specific connection — particularly with Sadleir — was probably lost on American readers.

Eytinge assumed in illustrating Merdle's party (facing page 323 in Chapter 12, "In which a Great Patriotic Conference is Holden") that the reader would already be acquainted with Merdle from this passage in the first book, set in the Merdle "establishment" in Harley Street, Cavendish Square:

Mr. Merdle was immensely rich; a man of prodigious enterprise; a Midas without the ears, who turned all he touched to gold. He was in everything good, from banking to building. He was in Parliament, of course. He was in the City, necessarily. He was Chairman of this, Trustee of that, President of the other. The weightiest of men had said to projectors, "Now, what name have you got? Have you got Merdle?" And, the reply being in the negative, had said, "Then I won't look at you."

This great and fortunate man had provided that extensive bosom which required so much room to be unfeeling enough in, with a nest of crimson and gold some fifteen years before. It was not a bosom to repose upon, but it was a capital bosom to hang jewels upon. Mr. Merdle wanted something to hang jewels upon, and he bought it for the purpose. Storr and Mortimer [goldsmiths and jewellers to Queen Victoria since her girlhood until 1839] might have married on the same speculation.

Like all his other speculations, it was sound and successful. The jewels showed to the richest advantage. The bosom [of Mrs. Merdle] moving in Society with the jewels displayed upon it, attracted general admiration. Society approving, Mr. Merdle was satisfied. He was the most disinterested of men, — did everything for Society, and got as little for himself out of all his gain and care, as a man might.

That is to say, it may be supposed that he got all he wanted, otherwise with unlimited wealth he would have got it. But his desire was to the utmost to satisfy Society (whatever that was), and take up all its drafts upon him for tribute. He did not shine in company; he had not very much to say for himself; he was a reserved man, with a broad, overhanging, watchful head, that particular kind of dull red colour in his cheeks which is rather stale than fresh, and a somewhat uneasy expression about his coat-cuffs, as if they were in his confidence, and had reasons for being anxious to hide his hands. In the little he said, he was a pleasant man enough; plain, emphatic about public and private confidence, and tenacious of the utmost deference being shown by every one, in all things, to Society. In this same Society (if that were it which came to his dinners, and to Mrs. Merdle's receptions and concerts), he hardly seemed to enjoy himself much, and was mostly to be found against walls and behind doors. Also when he went out to it, instead of its coming home to him, he seemed a little fatigued, and upon the whole rather more disposed for bed; but he was always cultivating it nevertheless, and always moving in it — and always laying out money on it with the greatest liberality. [Book One, Chapter 21, "Mr. Merdle's Complaint," p. 143]

The Dorrits, making an upper middle class version of the Grand Tour, cross paths with Mrs. Merdle and her son by a previous marriage, Edmund Sparkler, at Martigny. Meanwhile, back in Cavendish Square, her banker-husband entertains the politically influential Barnacles to promote Edmund's interests in Book 2, Chapter 12, ""In Which a Great Patriotic Conference is Holden." The foregrounded juxtaposition of the fashionably dressed, older man with extensive shirt cuffs — undoubtedly, Mr. Merdle — seated beside a younger man in formal dress suggests that Eytinge has realised the following passage:

Mr. Tite Barnacle, who, like Dr. Johnson's celebrated acquaintance, had only one idea in his head and that was a wrong one, had appeared by this time. This eminent gentleman and Mr. Merdle, seated diverse ways and with ruminating aspects on a yellow ottoman in the light of the fire, holding no verbal communication with each other, bore a strong general resemblance to the two cows in the Cuyp picture over against them. [325]

The remaining six figures in the illustration are the assorted younger members of the Barnacle clan and lords of the Circumlocution Office, since the supreme Barnacle, Lord Decimus, has yet to arrive. Behind Merdle's companion is the attorney "Bar," clearly identifiable by virtue of his monocle (first introduced in Book One, Chapter 21, "Mr. Merdle's Complaint"). Whereas Dickens focuses on Merdle's inner discomfort, his feeling of being a rank stranger and utter interloper in his own drawing room, Eytinge gives us merely the placid and elegant exterior. In the absence of specific description of the financier, the American illustrator has had to improvise, giving him lean features, swept back blond hair, a double chin, and rigid posture. This pillar-like figure does not immediately suggest ineptitude or uneasiness, nor do his hands imply anxiety, but he does seem "reserved," and his head is indeed "broad, overhanging, watchful." Perhaps his skeletal thinness is intended to suggest his lack of enjoyment of expensive foodstuffs and rich meals. The emphasis on the rounded end of the ottoman in the illustration suggests that Merdle is not just seated, but enthroned, but Eytinge has created that degree of isolation between the host and his guests which prepares the reader for Merdle's eventual suicide.

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U P, 1990.

Davis, Paul. Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit, il. Sol Eytinge, Junior. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1871.

Ranlett, John. "Railways." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia. Ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Pp. 663-665.

Last modified 15 May 2011