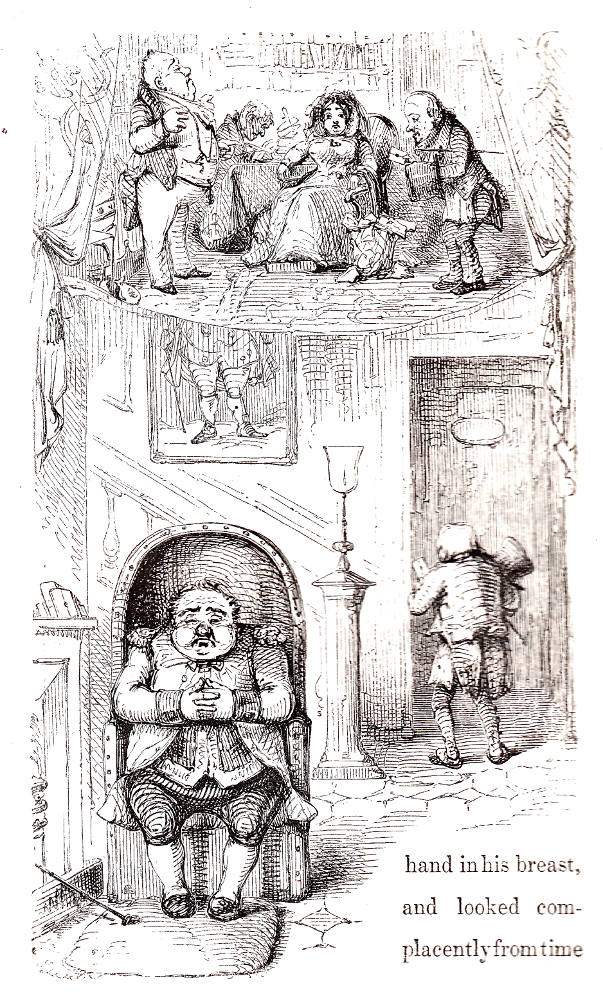

"You're in spirits, Tugby, my dear."

A. A. Dixon

1906

Lithographic reproduction of watercolour

12.2 cm high x 8.1 cm wide

Second illustration for The Christmas Books, Collins' Pocket Edition (1906), facing page 160.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

The good-natured groceress who "carries" Trotty in his dream-vision marries the venial Tugby, Sir Joseph Bowley's porter, and changes the name of her "firm" accordingly. She and her husband enjoy their creature comforts (epitomised by muffins and Sally Lunns), and forget about their neighbors' suffering. [Commentary continued below.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated from The Fourth Quarter

Fat company, rosy-cheeked company, comfortable company. They were but two, but they were red enough for ten. They sat before a bright fire, with a small low table between them; and unless the fragrance of hot tea and muffins lingered longer in that room than in most others, the table had seen service very lately. But all the cups and saucers being clean, and in their proper places in the corner-cupboard; and the brass toasting-fork hanging in its usual nook and spreading its four idle fingers out as if it wanted to be measured for a glove; there remained no other visible tokens of the meal just finished, than such as purred and washed their whiskers in the person of the basking cat, and glistened in the gracious, not to say the greasy, faces of her patrons.

This cosy couple (married, evidently) had made a fair division of the fire between them, and sat looking at the glowing sparks that dropped into the grate; now nodding off into a doze; now waking up again when some hot fragment, larger than the rest, came rattling down, as if the fire were coming with it.

It was in no danger of sudden extinction, however; for it gleamed not only in the little room, and on the panes of window-glass in the door, and on the curtain half drawn across them, but in the little shop beyond. A little shop, quite crammed and choked with the abundance of its stock; a perfectly voracious little shop, with a maw as accommodating and full as any shark's. Cheese, butter, firewood, soap, pickles, matches, bacon, table-beer, peg-tops, sweetmeats, boys' kites, bird-seed, cold ham, birch brooms, hearth-stones, salt, vinegar, blacking, red-herrings, stationery, lard, mushroom-ketchup, staylaces, loaves of bread, shuttlecocks, eggs, and slate pencil; everything was fish that came to the net of this greedy little shop, and all articles were in its net. How many other kinds of petty merchandise were there, it would be difficult to say; but balls of packthread, ropes of onions, pounds of candles, cabbage-nets, and brushes, hung in bunches from the ceiling, like extraordinary fruit; while various odd canisters emitting aromatic smells, established the veracity of the inscription over the outer door, which informed the public that the keeper of this little shop was a licensed dealer in tea, coffee, tobacco, pepper, and snuff.

Glancing at such of these articles as were visible in the shining of the blaze, and the less cheerful radiance of two smoky lamps which burnt but dimly in the shop itself, as though its plethora sat heavy on their lungs; and glancing, then, at one of the two faces by the parlour-fire; Trotty had small difficulty in recognising in the stout old lady, Mrs. Chickenstalker: always inclined to corpulency, even in the days when he had known her as established in the general line, and having a small balance against him in her books.

The features of her companion were less easy to him. The great broad chin, with creases in it large enough to hide a finger in; the astonished eyes, that seemed to expostulate with themselves for sinking deeper and deeper into the yielding fat of the soft face; the nose afflicted with that disordered action of its functions which is generally termed The Snuffles; the short thick throat and labouring chest, with other beauties of the like description; though calculated to impress the memory, Trotty could at first allot to nobody he had ever known: and yet he had some recollection of them too. At length, in Mrs. Chickenstalker's partner in the general line, and in the crooked and eccentric line of life, he recognised the former porter of Sir Joseph Bowley; an apoplectic innocent, who had connected himself in Trotty's mind with Mrs. Chickenstalker years ago, by giving him admission to the mansion where he had confessed his obligations to that lady, and drawn on his unlucky head such grave reproach.

Trotty had little interest in a change like this, after the changes he had seen; but association is very strong sometimes; and he looked involuntarily behind the parlour-door, where the accounts of credit customers were usually kept in chalk. There was no record of his name. Some names were there, but they were strange to him, and infinitely fewer than of old; from which he argued that the porter was an advocate of ready-money transactions, and on coming into the business had looked pretty sharp after the Chickenstalker defaulters.

So desolate was Trotty, and so mournful for the youth and promise of his blighted child, that it was a sorrow to him, even to have no place in Mrs. Chickenstalker's ledger.

"What sort of a night is it, Anne?" inquired the former porter of Sir Joseph Bowley, stretching out his legs before the fire, and rubbing as much of them as his short arms could reach; with an air that added, "Here I am if it's bad, and I don't want to go out if it's good."

"Blowing and sleeting hard," returned his wife; "and threatening snow. Dark. And very cold."

"I'm glad to think we had muffins," said the former porter, in the tone of one who had set his conscience at rest. "It's a sort of night that's meant for muffins. Likewise crumpets. Also Sally Lunns."

The former porter mentioned each successive kind of eatable, as if he were musingly summing up his good actions. After which he rubbed his fat legs as before, and jerking them at the knees to get the fire upon the yet unroasted parts, laughed as if somebody had tickled him.

"You're in spirits, Tugby, my dear," observed his wife. [The Fourth Quarter, pp. 169-172]

Commentary

One may well wonder, examining the cosy parlour scene, where the shop, described in such minute detail in the text, has gone, for Dixon offers the reader not even a suggestion of mercantile activity in this pleasant domestic scene. And, more to the point, where have the Hungry Forties gone in Dixon's turn-of-the-century illustrations for The Christmas Books. Poverty, starvation, mass unemployment, unjust incarceration, and working class rebellion — so obvious in the original novellas and in The Illustrated London News in the 1840s are nowhere to be found in the Collins' Pocket Edition illustrations.

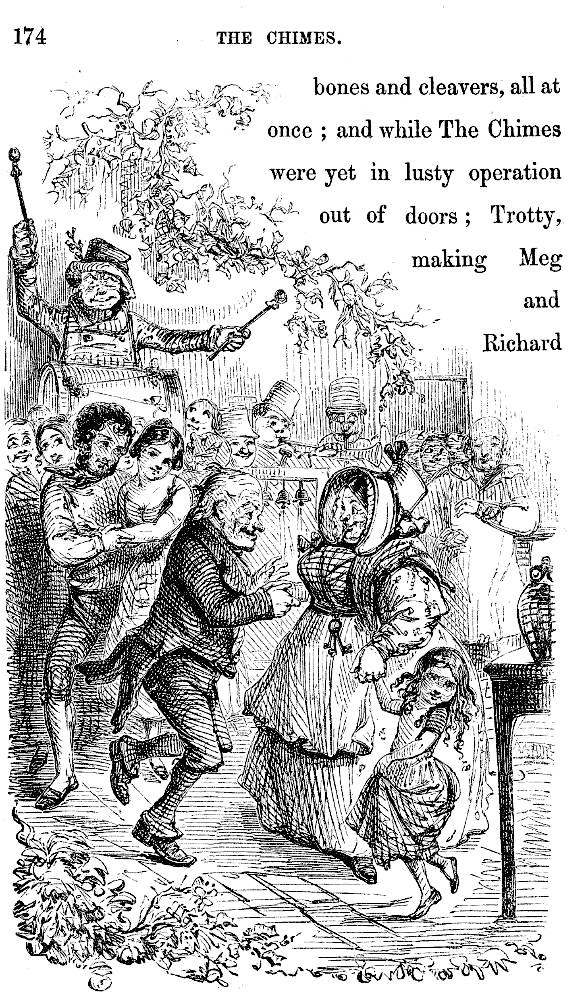

Since Mrs. Chickenstalker and Tugby are relatively minor characters in the The Chimes, the petite bourgeois couple do not appear together in most of the nineteenth-century illustrations for the novella. This cautionary tale for the Hungry Forties focuses on the dire fates of a number of more significant characters in Trotty's dream, with the wood-engravings of John Leech and his colleagues featuring Richard's alcoholism, Meggy's poverty and suicide, Lilian's prostitution, and Will Fern's imprisonment for rick-burning. The scene in the original thirteen-illustration sequence that most closely conveys an uncharacteristically jolly moment in an otherwise Chartist text is John Leech's The New Year's Dance, which occurs after Trotty awakens. As a member of the insensitive group of exploiters in the novella, Tugby does not appear in the concluding dance celebrating not only the marriage of Richard and Meg but also social concord, or at least working-class solidarity. Rather, he appears in several plates preceding the dream, but (unlike Dixon's figure) is physically repulsive, obese, and complacent. In other words, the original illustrators do not alleviate the sense of social catastrophe in the scenes of Trotty's dream by showing this well-fed couple by their well provisioned fireside.

Whereas Punch cartoonist and political satirist John Leech in the original scarlet volume published in December 1844 did not spare Dickens's readers knowledge of the sufferings of the principal characters, E. A. Abbey in the in the American Household Edition does not dwell on these tribulations, offering only two illustrations for the story, but British Household Edition illustrator Fred Barnard chose to contrast Will Fern's indignation at the complacency of the governing classes in "Whither thou goest, I can Not go. . ." and the fireside ease of the corpulent Mr. and Mrs. Tugby in "You're in spirits, Tugby, my dear." These images of Sir Joseph Bowley's porter are intended to arouse the viewer's antipathy, whereas Dixon presents him as a kind-faced, comfortable middle-class burgher in his well-furnished parlour, basking in the glow of the fire and chatting affably with his wife. Contributing to this sense of material comfort are Tugby's wing chair, Mrs. Tugby's footrest, the sleeping cat, and sideboard filled with china in the background. The happy, middle-aged couple are notable by their absence in the sequence of illustrations that Harry Furniss produced four years after Dixon's, as he chooses instead to focus on the "dream-vision" plights of Trotty's daughter and fiancé in Margaret and Richard.

Related Illustrations from Other Editions, 1843-1910

Left, John's Leech's "New Year's Dance" and, right, "Sir Joseph Bowley's" (1844). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Left: Fred Barnard's "You're in spirits, Tugby, my dear" (1878); centre: Fred Barnard's ""Whither thou goest, I can Not go; where thou lodgest, I do Not lodge; thy people are Not my people; Nor thy God my God!" (1878); and right: Harry Furniss's "Margaret and Richard"(1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

References

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Canton, Ohio: Ohio U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge. New Haven: Yale U. P., 1990.

Dickens, Charles. The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells That Rang an Old Year Out and a New Year In. Il. John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1844 [dated 1845].

Dickens, Charles. The Christmas Books. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

Dickens, Charles. The Christmas Books. Il. Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 8.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Il. E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-118.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Welsh, Alexander. "Time and the City in The Chimes." Dickensian 73, 1 (January 1977): 8-17.

Victorian

Web

Illus-

tration

A. A.

Dixon

Next

Great

Expectations

Next

Last modified 29 March 2014