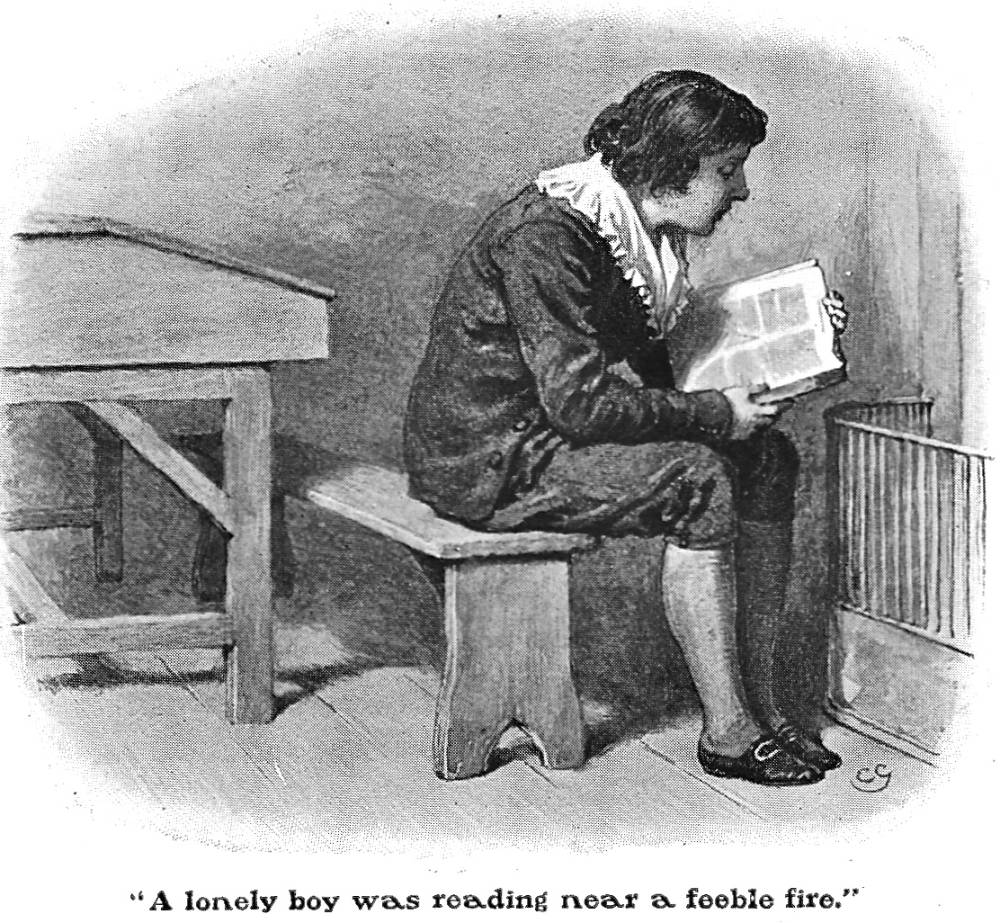

"A lonely boy was reading" (1905), the headpiece for Stave Two, "The First of the Three Spirits," 9.1 cm by 10 cm, vignetted (26). [Image showing both the caption and the illustration’s location as a headpiece.]

Passage Illustrated: Young Master Scrooge

They went, the Ghost and Scrooge, across the hall, to a door at the back of the house. It opened before them, and disclosed a long, bare, melancholy room, made barer still by lines of plain deal forms and desks. At one of these a lonely boy was reading near a feeble fire; and Scrooge sat down upon a form, and wept to see his poor forgotten self as he used to be.

Not a latent echo in the house, not a squeak and scuffle from the mice behind the paneling, not a drip from the half-thawed water-spout in the dull yard behind, not a sigh among the leafless boughs of one despondent poplar, not the idle swinging of an empty store-house door, no, not a clicking in the fire, but fell upon the heart of Scrooge with a softening influence, and gave a freer passage to his tears.

The Spirit touched him on the arm, and pointed to his younger self, intent upon his reading. Suddenly a man, in foreign garments: wonderfully real and distinct to look at: stood outside the window, with an ax stuck in his belt, and leading by the bridle an ass laden with wood.

"Why, it's Ali Baba!" Scrooge exclaimed in ecstasy. "It's dear old honest Ali Baba. Yes, yes, I know. One Christmas time, when yonder solitary child was left here all alone, he did come, for the first time, just like that. Poor boy. And Valentine," said Scrooge, "and his wild brother, Orson; there they go. And what's his name, who was put down in his drawers, asleep, at the Gate of Damascus; don't you see him? And the Sultan's Groom turned upside down by the Genii; there he is upon his head. Serve him right. I'm glad of it. What business had he to be married to the Princess?" [Stave Two, "The First of the Three Spirits," 32]

Commentary

In this plate Brock provides a flashback to Scrooge's time as a schoolboy, when all his classmates had left for the Christmas holidays. The boy's family have not called for him, and had to remain at the school, a cold, deserted building where the characters in the books he reads are his only companions. Brock does not make the young Scrooge, who is absorbed in his reading and envisioning the characters from The Arabian Nights, Robinson Crusoe, and Valentine and Orson, seem especially lonely or dejected, and his reading spot beside the fireplace should be comfortable, despite the absence of either a cushion or any actual fire. Unlike American illustrator Sol Eytinge, Junior, who has provided a similar realisation in the 1868 Ticknor-Fields single volume edition of the Carol, Brock shows neither the Spirit of Christmas Past nor the mature Scrooge in his night-cap and night-gown as observers of or reflectors on the scene. Rather, Brock focuses upon the young reader and the crowding creatures of his imagination: (left to right) Man Friday, Robinson Crusoe in goatskins, Valentine the knight and his twin, Orson the wild man, and Ali Baba with his donkey, all sketched in lightly and seeming to emanate from the fireplace. In company with these literary companions, young Scrooge here (dressed in Regency fashion) seems neither disconsolate nor lonely, although silent reading is indeed a solitary activity.

Brock makes clear that as a boy Scrooge, like young Dickens, was thoroughly attuned to the power of the invisible world of "Fancy," that is, the realm of literature and the imagination. Brock includes five characters, but not the groom at the Damascus Gate or Robinson Crusoe's green parrot. Previous illustrators after John Leech have generally not had space in their programs to reflect upon Scrooge's emotionally challenged school days, even though his father's rejection led to the mature businessman's asserting an uncharitable, anti-Christmas sentiment. Charles Green's approach (1912) is far more low-key and far less imaginative than Brock's here. Compare, too, Brock's treatment of the literary characters who, like the Spirits on Christmas Eve, "visited" Scrooge, with Eytinge's depiction of just the Arabian Nights figure in The Vision of Ali Baba, vignette for "Stave 2. The First of the Three Spirits" (see below). As a realist with a psychological bent, Green (working in the twentieth century and responding to the new medium of film in these illustrations) focuses on the boy who is reading by the cold fireplace, and does not show the other characters from Dickens's childhood reading in The Spirit of Scrooge's Former Self, or, A lonely boy who was reading near a feeble fire (see below).

More novel than Brock's approach here is that of impressionistic illustrator Harry Furniss (1910), who, just five years after Brock's edition, created a composite image to give readers an impression of the school and the Spirit of Christmas Present, as well as a representation of young Scrooge as a solitary reader, The First of the Three Spirits (see below) in the The Christmas Books. Neither Fred Barnard in the 1878 Chapman and Hall Household Edition illustrations nor E. A. Abbey in the 1876 Harper and Brothers volume of Christmas Stories had space to admit a study of the child Scrooge as a social isolate, vivifying the Wordsworthian maxim "The Child is Father of the Man" from the lyric "My Heart Leaps Up" (1802).

Relevant Illustrations from various editions, 1868-1915

Left: Harry Furniss's innovative interpretation of Scrooge's seeing his former self, abandoned at the holidays, in The First of the Three Spirits (1910). Right: Green depicts Scrooge as a solitary reader in The Spirit of Scrooge's Former Self, or, A lonely boy who was reading near a feeble fire, in the 1912 Pears volume.

Above: Eytinge's headpiece for the second stave conveying Scrooge's joy at reconnecting with the characters from his childhood reading, The Vision of Ali Baba, vignette for "Stave 2. The First of the Three Spirits" (1868).

Above: Arthur Rackham's more prosaic view of Scrooge as a schoolboy, He produced a decanter of curiously light wine and a block of curiously heavy cake (1915).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867. X.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

_____. A Christmas Carol and The Cricket on the Hearth. Illustrated by C. E. [Charles Edmund] Brock. London: J. M. Dent, 1905; New York: Dutton, rpt., 1963.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A. & F. Pears, 1912.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. 1.

Hearn, Michael Patrick, ed. The Annotated Christmas Carol. New York: Avenel, 1976.

Created 20 September 2015

Last modified 28 May 2020