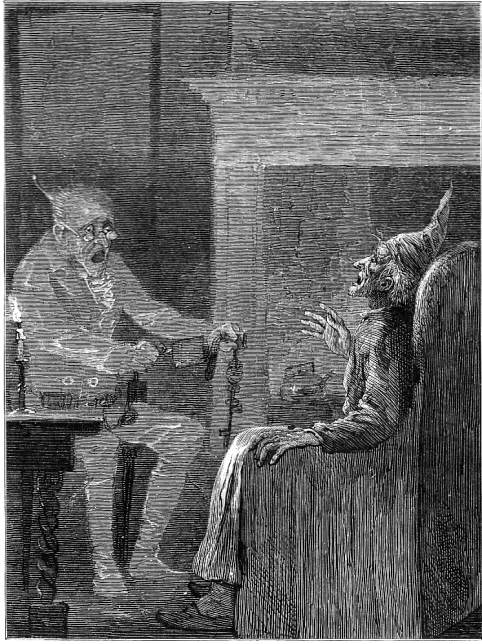

U[Marley's Ghost]

Charles Edmund Brock

1905

5.6 x 2.5 cm, vignetted

Uncaptioned title-page vignette for Dickens's A Christmas Carol, title-page vignette.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Charles Edmund Brock —> Charles Dickens —> Next]

U[Marley's Ghost]

Charles Edmund Brock

1905

5.6 x 2.5 cm, vignetted

Uncaptioned title-page vignette for Dickens's A Christmas Carol, title-page vignette.

[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

"It's humbug still!" said Scrooge. "I won't believe it."

His colour changed though, when, without a pause, it came on through the heavy door, and passed into the room before his eyes. Upon its coming in, the dying flame leaped up, as though it cried, "I know him; Marley's Ghost!" and fell again.

The same face: the very same. Marley in his pigtail, usual waistcoat, tights and boots; the tassels on the latter bristling, like his pigtail, and his coat-skirts, and the hair upon his head. The chain he drew was clasped about his middle. It was long, and wound about him like a tail; and it was made (for Scrooge observed it closely) of cash-boxes, keys, padlocks, ledgers, deeds, and heavy purses wrought in steel. His body was transparent, so that Scrooge, observing him, and looking through his waistcoat, could see the two buttons on his coat behind.

Scrooge had often heard it said that Marley had no bowels, but he had never believed it until now.

No, nor did he believe it even now. Though he looked the phantom through and through, and saw it standing before him; though he felt the chilling influence of its death-cold eyes; and marked the very texture of the folded kerchief bound about its head and chin, which wrapper he had not observed before: he was still incredulous, and fought against his senses. [Stave One, "Marley's Ghost," 17-18]

A Christmas Carol begins with the assertion that "Marley was dead: to begin with" (1906 edition, p. 3) The book's original illustrator, John Leech, makes the celebrated meeting between the inveterate miser and his old partner — in essence, his psychological twin — closely follow the text’s description of that meeting in Marley's Ghost (see below). One receives little sense of Scrooge's bravado described in the text. Nevertheless, Leech set the pattern for later illustrators: the arrival of the wandering spirit produces a definite emotional reaction in a manl not accustomed to express any emotion other than disgust for sentimentality and other such emotional "humbug." E. A. Abbey in the American Household Edition and the Ticknor-Fields twenty-fifth anniversary edition illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. both underscore the psychological significance of Marley's visit seven years after his death. Brock, who may not have been able to consult their work, placies the readers in the vantage point of the miser, since we see what Scrooge initially sees: a thin, middle-aged man wrapped in a chain of cash-boxes, keys, locks, and ledgers, uncomfortably constricted and unable to move. The illustrator therefore employs the chain, inherited from Leech and Fred Barnard, as a visual commentary on his impotence as a mere spirit: he can no longer intervene in human affairs, but must merely observe the suffering he might once have addressed. Now the constrictor of materialism has him firmly in its grip visually as in life it controlled and confined him spiritually.

Left: Eytinge's Marley]s Ghost. Right: Leech's interpretation of the ghost and his former partner, Marley's Ghost. (1843)

Left: Harry Furniss's composite scene in which a suspicious Scrooge scowls at the wandering spirit, Marley's Ghost (1910). Right: Fred Barnard's equally humorous rendering of the scene, Marley's Ghost. (1878)

Above: Abbey's full-page rendering of the scene as a frontispiece, "What do you want with me?" (1876).

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

_____. Christmas Books, illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. A Christmas Carol and The Cricket on the Hearth. Illustrated by C. E. [Charles Edmund] Brock. London: J. M. Dent, 1905; New York: Dutton, rpt., 1963.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A. & F. Pears, 1912.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. 1.

Hearn, Michael Patrick, ed. The Annotated Christmas Carol. New York: Avenel, 1976.

Created 13 September 2015

Last modified 14 March 2020