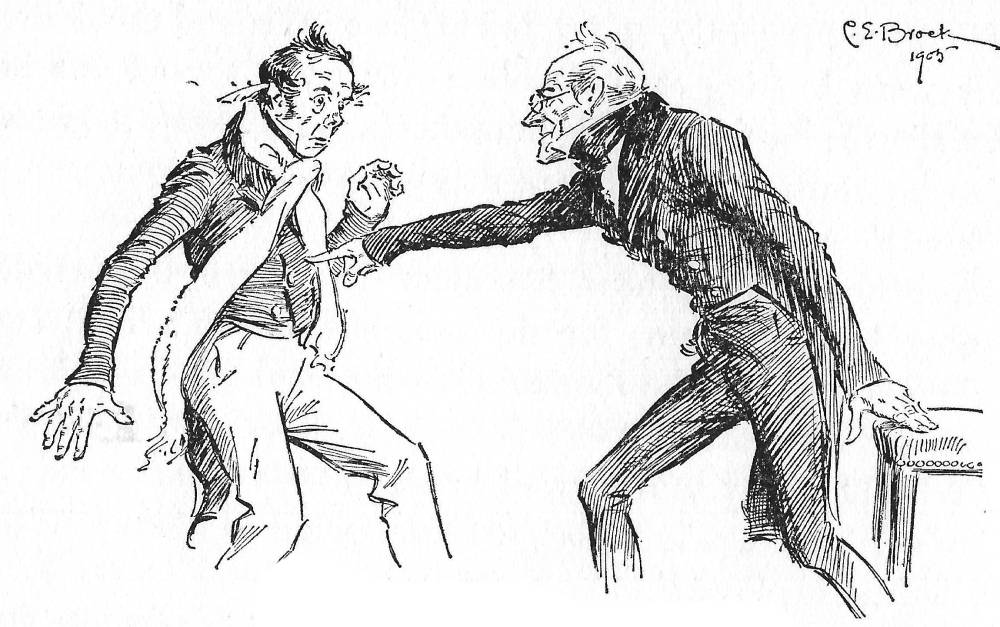

"I am about to raise your salary" (1905), a half-page illustration for Stave Five, "The End of It," 6 cm by 9.5 cm, vignetted (100) is Brock's realisation of Scrooge's becoming a better man and a better master by improving his employee's standard of living since in both Christmas Present and Christmas Yet to Come he has seen for himself how the Cratchits live. The scene is among both the most amusing and heart-warming in the 1951 cinematic adaptation of A Christmas Carol, starring Alastair Sim as the much-changed miser and Welsh actor Mervyn Jones as the long-suffering clerk.

Passage Illustrated

No Bob. He was full eighteen minutes and a half behind his time. Scrooge sat with his door wide open, that he might see him come into the Tank.

His hat was off, before he opened the door; his comforter too. He was on his stool in a jiffy; driving away with his pen, as if he were trying to overtake nine o'clock.

"Hallo," growled Scrooge, in his accustomed voice, as near as he could feign it. "What do you mean by coming here at this time of day?"

"I'm very sorry, sir," said Bob. "I am behind my time."

"You are?" repeated Scrooge. "Yes. I think you are. Step this way, if you please."

"It's only once a year, sir," pleaded Bob, appearing from the Tank. "It shall not be repeated. I was making rather merry yesterday, sir."

"Now, I'll tell you what, my friend," said Scrooge, "I am not going to stand this sort of thing any longer. And therefore," he continued, leaping from his stool, and giving Bob such a dig in the waistcoat that he staggered back into the Tank again; "and therefore I am about to raise your salary."

Bob trembled, and got a little nearer to the ruler. [Stave Five,"The End of It," 99-100]

Commentary: Rewarding Bob

Brock’s culminating scene, back at the office where Scrooge's story opens, in Bob Cratchit '...tried to warm himself at the candle', builds on the comic vein that he mined when Ebenezer Scrooge purchased the prize turkey for the Cratchits the day before. In a simple line drawing, Brock depicts a vigorous, energetic Scrooge who in playful spirit follows through on his commitment to the Spirit of Christmas to Come to be a better man and master. Here, then, Brock underscores Scrooge's acting on his new-found emotions, impulses, and Christmas (and Christian) spirit. Dickens’s and the illustrator’s conceptions of Christianity seem to be that acting in a charitable and generous manner to one's associates and employees ultimately benefits everyone. The way to a socially just, equitable, and caring society lies through the wealthy (the aristocracy, captains of industry, and sucessful business people such as Scrooge) embracing true Christian philanthropy and committing acts of selfless charity rather than through the government's creating demeaning union workhouses under the new Poor Law..

In A Christmas Carol Dickens calls for a change of heart in good men of business such as Scrooge, who must, argues Dickens, bridge the divide between management and labour, and take a personal interest in the lives of their employees. The culminating illustration economically communicates Scrooge's playfulness as he momentarily teases Bob before redefining their relationship on a much more personal basis. Henceforth, the cash nexus of Thomas Carlyle will henceforth no longer govern. Raising family-man Bob's wages to the standard set in the City will, moreover, ensure Bob's loyalty as an employee, so that Scrooge's treating him to a cup of punch in his own rooms (which is the subject of John Leech's final illustration) is likely to make Bob regard his employer as a surrogate father to his handicapped child. Undoubtedly, as Angnleszka Setecka, has speculated, Bob will seek to gratify his benevolent employer by devoted service and dedication to detail in his book-keeping. Thus, "Old Scrooge" becomes, in effect, an updated version of that paternalistic importer-exporter "Old Fezziwig" in whose counting-house he worked as a young clerk. This updating of the paternalistic Fezziwig in the person of the Victorian capitalist Scrooge is genuine rather than cosmetic, so that Scrooge's change of heart will effect improvements in the lives of the Cratchits, and his nephew, Fred, and probably countless others.

Illustrators after Leech have focussed Scrooge's confrontation with his own mortality in the churchyard scene at the end of the fourth stave, and have often neglected to show how Scrooge's change of heart subsequently informs his role as a capitalist and an employer, obliquely alluded to in Scrooge and Bob Cratchit; or, The Christmas Bowl (see below), the final plate in the 1843 series. Dickens has fully integrated this tailpiece into the text as if it is to have authority equal to that of the closing lines in describing what sort of employer Scrooge becomes. Readers have often regarded the conclusion of the novella as demonstrating how affection, good-will, fellow-feeling, and charity win out over the capitalist logic of profit and loss. But perhaps the miser is embracing the new economic logic that increased spending will cure the depression of The Hungry Forties, realizing that circulating capital is preferable to hoarding it.

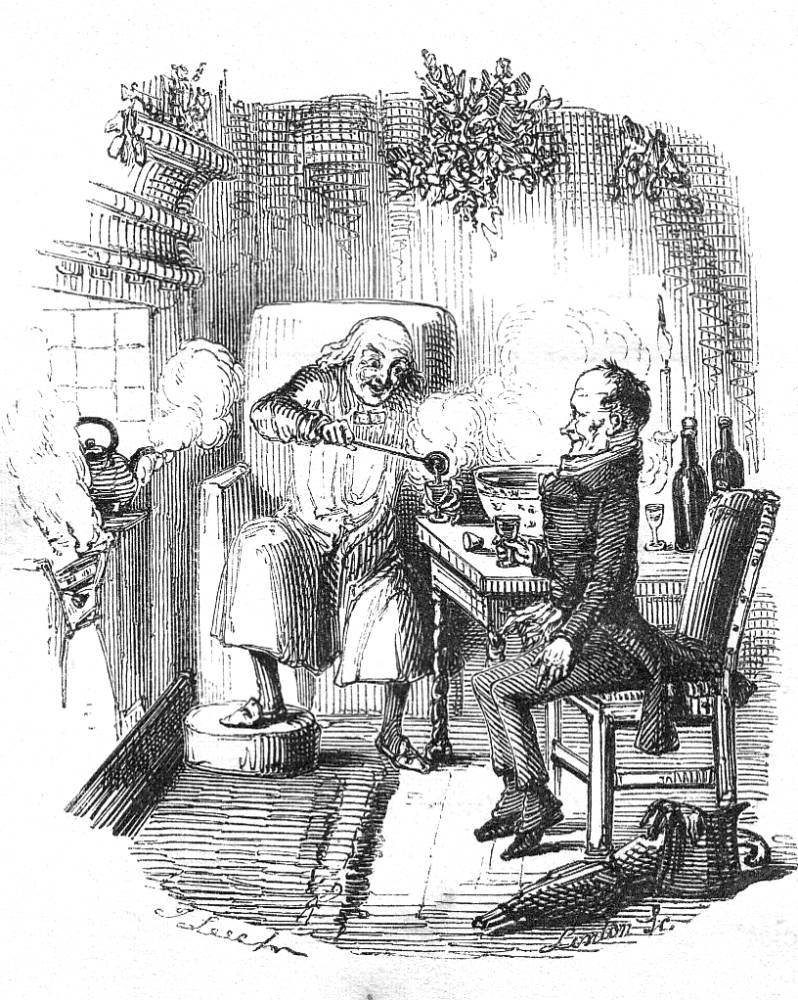

In the original text, the narrator establishes the scene as the former miser's office on the morning after Christmas. Dickens indicates in Scrooge's direct discourse an intention to enact the part of his former employer, the old-fashioned, somewhat paternalistic old Fezziwig; indeed, this intention seems consistent with the notions of labour-management relations that the Sage of Chelsea, Dickens's friend Thomas Carlyle advocated. We can reasonably assume, then, that the Leech and Green scenes involving the festive consumption of punch ("smoking Bishop") occur that very afternoon, although Green does not indicate its location, whereas Leech situates the convivial scene in Scrooge's own parlour, that same room in which he encountered both Marley's Ghost and the Ghost of Christmas Present. Although Leech has included just one small wood-block engraving to demonstrate Scrooge's change of heart as an employer, of the other nineteenth-century illustrators of the novella, only the American (nevertheless, an associate of Dickens) Sol Eytinge, Junior, in the 1868 Ticknor and Fields edition has devoted a significant proportion of his program to the new, improved Scrooge in the concluding stave, showing him with child-like glee pulling on his socks on Christmas morning and smiling broadly as he steps out of his office the next day to shock his clerk with news of a salary increase, in "I'll raise your salary" (see below). Indeed, although three Eytinge illustrations accompany "The End of It," the most pertinent for this consideration of "rebooted capitalist" is "I'll raise your salary", in which a jolly Scrooge pokes a stunned and speechless Bob Cratchit in the ribs and "button-holes" him to rush out and buy a new coal-scuttle right away: the conspicuous consumption has begun.

In contrast to Brock's treatment, Charles Green merely revised Scrooge and Bob Cratchit (1912) simply revised Leech's caricatural illustration of punch bowl scene. Brock's culminating illustration, unlike Green's and Leech's, reveals Scrooge's rascalityand his school-boy playfulness by his teasing Bob with dismissal before revealing that he is actually raising the clerk's wages to the standard of the City's counting-houses.

Relevant Illustrations from various editions, 1843-1912

Left: Green's interpretation of Scrooge's entertaining his long-suffering clerk, Scrooge and Bob Cratchit. Centre: Eytinge depicts a Scrooge who will begin to spend like Santa in "I'll raise your salary", in the 1868 single-volume edition. Right: Leech's tailpiece of Scrooge as a good a master and man as the good old world ever knew, entertaining his clerk, in Scrooge and Bob Cratchit; or, The Christmas Bowl (1843).

Above: Eytinge's demonstration that Scrooge is a changed man, in "Scrooge Awakes," vignette for "Stave 5. The End of It" (1868).

Other Illustrations for A Christmas Carol (1843-1915)

- John Leech's original 1843 series of eight engravings for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 1867-68 illustrations for two Ticknor & Fields editions for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- E. A. Abbey's 1876 illustrations for The American Household Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- Fred Barnard's 1878 illustrations for The Household Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- A. A. Dixon's 1906 Collins Pocket Edition for Dickens's Christmas Books

- Charles Green's 1892 illustrations in A & F Pears Centenary Edition of Dickens's A Christmas Carol (1912)

- Harry Furniss's 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition of Dickens's Christmas Books

- A selection of Arthur Rackham's 1915 illustrations for Dickens's A Christmas Carol

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books, illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_______. Christmas Books, illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_______. Christmas Books, illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_______. Christmas Books, illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

_______. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas, illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall,1843.

_______. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas, illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

_______. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas, illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

_______. A Christmas Carol and The Cricket on the Hearth, illustrated by C. E. [Charles Edmund] Brock. London: J. M. Dent, 1905; New York: Dutton, rpt., 1963.

_______. A Christmas Carol, illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

_______. Christmas Stories, illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. 1.

Hearn, Michael Patrick, ed. The Annotated Christmas Carol. New York: Avenel, 1976.

Langley, Noel, screenwriter. Scrooge; or, Charles Dickens's "A Christmas Carol". London: Renown Rank, 1951.

Patten, Robert L. "Dickens Time and Again." Dickens Studies Annual 2 (1972): 163-196.

Setecka, Angnleszka. "Time for Balancing Your Books": A Christmas Carol and the Capitalist Logic of Exchange and Consumption." Paper given at "Queen Anne to Queen Victoria." Warsaw, Poland:The English Institute, 24 September 2015.

Created 20 October 2015

Last modified 2 July 2020