"You might, from your appearance, be the wife of Lucifer," said Miss Pross, in her breathing. "Nevertheless, you shall not get the better of me. I am an Englishwoman." (p. 169) by Fred Barnard. 1874. 10.7 x 13.8 cm. (4 ¼ by 5 ½ inches, framed). Amidst signs of hurried packing Madame Defarge confronts Miss Pross in Lucie's rooms, as yet unaware that the English party have already passed the Paris barrier, in Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book III, "The Track of a Storm," Chap. xiv, "The Knitting Done," originally in the thirty-first weekly part (26 November 1859) in All the Year Round, as well as in the December 1859 illustrated monthly number.

Commentary: When Continents of Experience Collide.

In Barnard's sequence, Miss Pross is not a wizened little woman who is an anxious mother hen to her "ladybird," Lucie Manette; rather, early in the sequence, in And smoothing her rich hair with as much pride, he establishes her as a physically formidable woman, although certainly no great beauty. Now, animated by the power of love, she confronts the Tigress of Saint Antoine, the predatory Madame Defarge, cunning, powerful, — and in Dickens's text beautiful as well as ferocious:

Madame Defarge looked coldly at her, and she said, "the wife of Evrémonde; where is she?"

It flashed upon Miss Pross's mind that the doors were all standing open, and would suggest the flight. Her first act was to shut them all. She then placed herself before the door of the chamber which Lucie had occupied. [171]

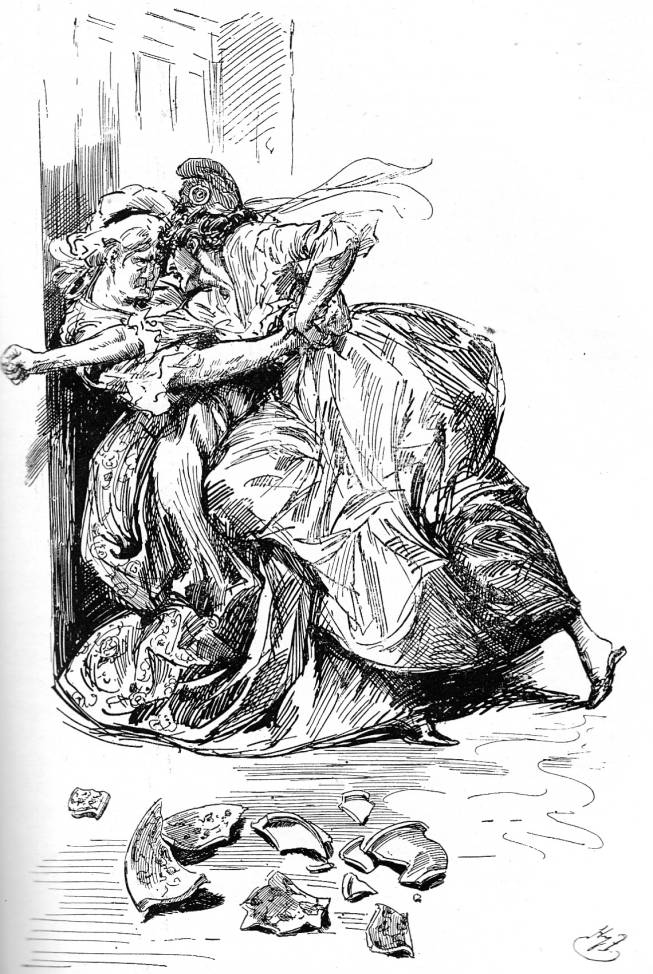

Thus, Barnard pits against one another two equally matched viragoes, burly, indomitable, and determined. Whereas Dickens describes Madame Defarge as wearing a robe as she makes her way through the streets, Barnard has given pantaloons of the Emilia Bloomer variety, thereby intensifying her masculine character. Though slighter and more anxious by nature, Miss Pross as Dickens describes her is formidable in a very different way:

Miss Pross had nothing beautiful about her; years had not tamed the wildness, or softened the grimness, of her appearance; but she, too, was a determined woman in her different way, and she measured Madame Defarge with her eyes, every inch. [171]

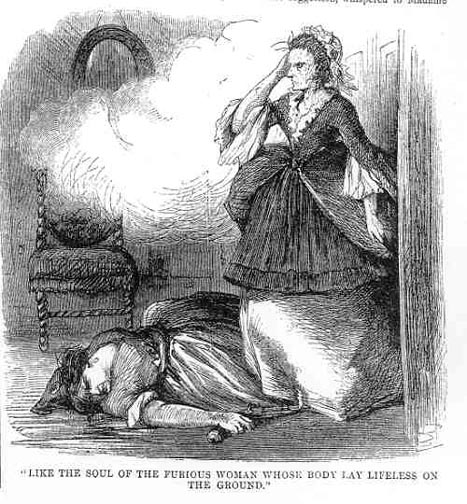

John McLenan in the series for the American serialisation published in Harper's Weekly chose to focus on the moment in which, the hidden pistol having been discharged, the French woman lies died at the feet of the English woman in Like the soul of the furious woman whose body lay lifeless on the ground in the second illustration for 26 November 1859 (765). McLenan's Madame Defarge, a young woman with a beautiful face, lies dead, her pistol still in her grip as a cloud of exploded gunpowder fills the room and the aged, formally dressed Miss Pross holds her hand to her head in token of her sudden deafness. The picture and barley cane-twist chair in the background connect this scene with that in which Doctor Manette returned from his fruitless quest to have his son-in-law released after the trial (the headnote to the November 12th instalment). In contrast, in the title-page vignette of the 1860 dramatic adaptation and again in Furniss's early twentieth-century treatment, the focus at the end of the narrative is not on Carton's sacrifice (written out, in fact, in the popular 1860s dramatic adaptation by Fox Cooper), but on the confrontation between devoted love and inveterate hatred — or between the determined "Briton" and the physically powerful French woman.

In David O. Selznick's epic 1935 film adaptation, starring Ronald Coleman as Sydney Carton, Edna May Oliver's jingoistic tag line "I am an English woman" sets a triumphant note, and signals her emerging victorious in her wrestling match with the physically powerful, demonically-empowered Terese Defarge, played with sinister zest by an American actress of Bohemian descent, Blanche Yurka. Throughout this stunning cinematic adaptation, Yurka's Madame Defarge has been more than a match for the evil Marquis St. Evrémonde (Basil Rathbone), but falls, a victim of her own hubris, to the redoubtable English woman (Oliver) in one of those rare moments in cinema that brings down the house. Both Barnard and McLenan realised the emotional impact of the confrontation of these continents of experience, and the palpable triumph of love over hate that the outcome of their struggle for the pistol underscores. In the popular Fox Cooper adaptation, this was the climax of the three-hour stage production with a cast of over forty. The heightened emotion and hyperbolic and inflated language not so well suggested in the static Barnard engraving, as well as the female wrestling match set against an upper-middle-class backdrop (the upper apartments at Tellson's Bank, Paris), would certainly have appealed to the primarily working-class audiences at The Victoria Theatre, opposite Waterloo Railway Station in London.

Relevant Illustrations from Other Editions: 1859, 1860, and 1910

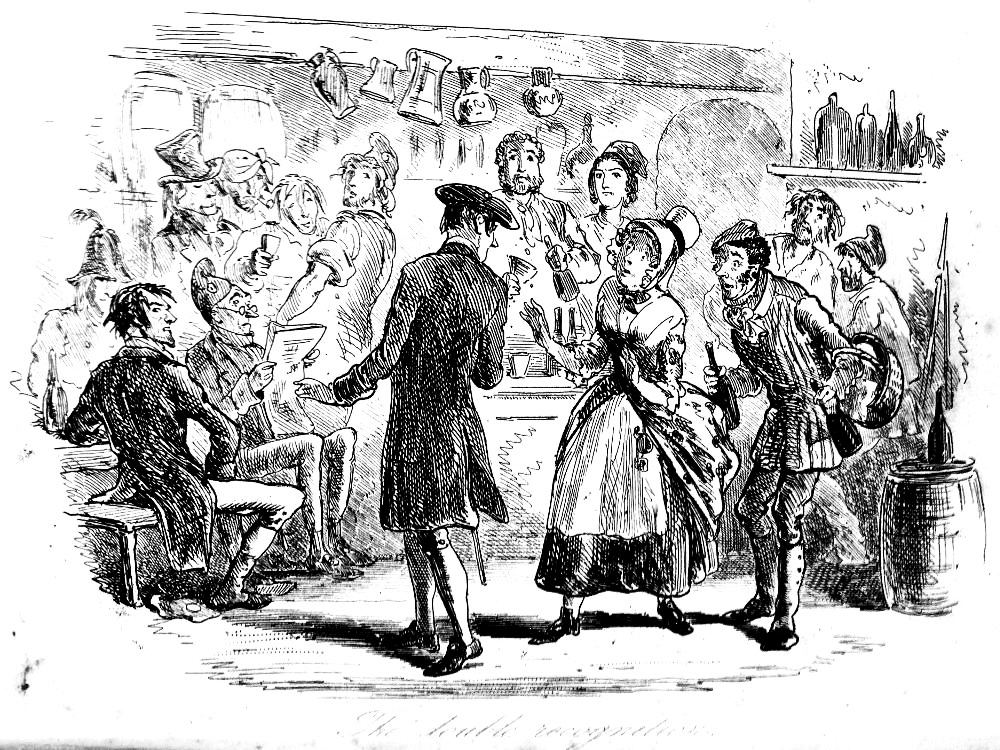

Left: The Double Recognition by Hablot Knight Browne in the seventh and final monthly number (December 1859) involves a very different Miss Pross. Right: Title-page for Fox Cooper's The Tale of Two Cities (July 1860 dramatic adaptation at The Victoria Theatre, London) depicts two equally attractive female antagonists wrestling for the pistol.

Left: McLenan's 26 November 1859 depiction of the conclusion of the struggle, Like the soul of the furious woman whose body lay lifeless on the ground. Right: Harry Furniss's highly kinetic Charles Dickens Library Edition version of the confrontation of two physically powerful and highly motivated antagonists in Book Three, Chapter Fourteen, Struggle between Miss Pross and Madame Defarge (1910).

Image scans and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. “Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859) Illustrated: A Critical Reassessment of Hablot Knight Browne's Accompanying Plates.” Dickens Studies Annual. 33 (2003): 109-158.

Bolton, H. Philip. Dickens Dramatized. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987.

Cooper, Fox. The Tale of Two Cities; or, The Incarcerated Victim of The Bastille. An Historical Drama, in a Prologue and Four Acts. London: John Dicks, 1860. Dicks' Standard Plays, No. 780. Rpt. Dickens Dramatized Series of Plays. Theatre Arts Press. Acheson, AB: Amazon.ca, 2015.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. The Grindstone. Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities. Vol. 2 frontispiece. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by John McLenan. Harper's Weekly. (26 November 1859): 765.

Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). London: Chapman and Hall, November 1859.

Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867. Vol. XIII.

Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. Vol. VIII.

_____. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London: Collins, 1905.

_____. A Tale of Two Cities, American Notes, and Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. XIII.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens. London: Educational Book, 1910.

Maxwell, Richard, ed. "Appendix I: "On The Illustrations." Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities. London: Penguin, 2003. Pp. 391-396.

Sanders, Andrew. "Introduction" to Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Vann, J. Don. "A Tale of Two Cities in All the Year Round, 30 April-26 November 1859." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp.71-72.

Woodcock, George. "Introduction" to Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.

Created 16 August 2016

Last modified 23 January 2026