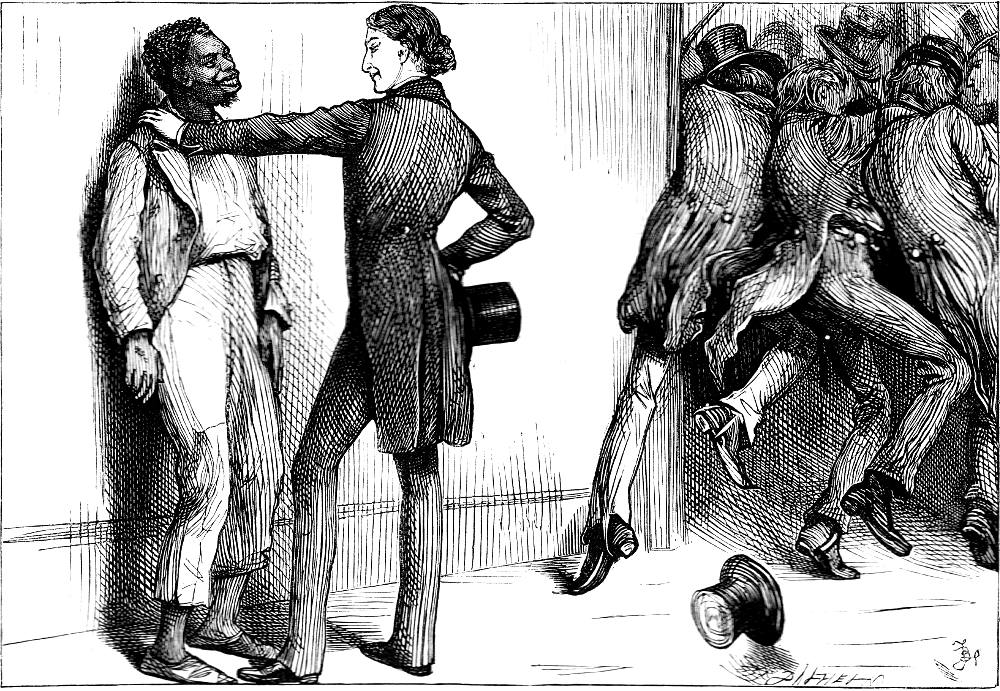

"It is in such enlightened means," said a voice, almost in Martin's ear, "That the bubbling passions of my country find a vent." (1872). — Fred Barnard's twenty-first regular illustration for Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit (Chapter XVI), page 129. [The ragged newsboys invade "The Screw" as the line-of-the-packet vessel lands in New York harbour — and Martin meets the Editor of the New York Rowdy Journal.] 10.6 cm by 13.8 cm, or 3 ¾ high by 5 ½ inches, framed. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Text Illustrated: Martin and Mark arrived in the TransAtlantic Port of New York

"Here’s the Sewer!" cried another. ‘Here’s the New York Sewer! Here’s some of the twelfth thousand of to-day’s Sewer, with the best accounts of the markets, and all the shipping news, and four whole columns of country correspondence, and a full account of the Ball at Mrs. White’s last night, where all the beauty and fashion of New York was assembled; with the Sewer’s own particulars of the private lives of all the ladies that was there! Here’s the Sewer! Here’s some of the twelfth thousand of the New York Sewer! Here’s the Sewer’s exposure of the Wall Street Gang, and the Sewer’s exposure of the Washington Gang, and the Sewer’s exclusive account of a flagrant act of dishonesty committed by the Secretary of State when he was eight years old; now communicated, at a great expense, by his own nurse. Here’s the Sewer! Here’s the New York Sewer, in its twelfth thousand, with a whole column of New Yorkers to be shown up, and all their names printed! Here’s the Sewer’s article upon the Judge that tried him, day afore yesterday, for libel, and the Sewer’s tribute to the independent Jury that didn’t convict him, and the Sewer’s account of what they might have expected if they had! Here’s the Sewer, here’s the Sewer! Here’s the wide-awake Sewer; always on the lookout; the leading Journal of the United States, now in its twelfth thousand, and still a-printing off: — Here’s the New York Sewer!"

"It is in such enlightened means," said a voice almost in Martin’s ear, "that the bubbling passions of my country find a vent."

Martin turned involuntarily, and saw, standing close at his side, a sallow gentleman, with sunken cheeks, black hair, small twinkling eyes, and a singular expression hovering about that region of his face, which was not a frown, nor a leer, and yet might have been mistaken at the first glance for either. Indeed it would have been difficult, on a much closer acquaintance, to describe it in any more satisfactory terms than as a mixed expression of vulgar cunning and conceit. This gentleman wore a rather broad-brimmed hat for the greater wisdom of his appearance; and had his arms folded for the greater impressiveness of his attitude. He was somewhat shabbily dressed in a blue surtout reaching nearly to his ankles, short loose trousers of the same colour, and a faded buff waistcoat, through which a discoloured shirt-frill struggled to force itself into notice, as asserting an equality of civil rights with the other portions of his dress, and maintaining a declaration of Independence on its own account. His feet, which were of unusually large proportions, were leisurely crossed before him as he half leaned against, half sat upon, the steamboat’s bulwark; and his thick cane, shod with a mighty ferule at one end and armed with a great metal knob at the other, depended from a line-and-tassel on his wrist. Thus attired, and thus composed into an aspect of great profundity, the gentleman twitched up the right-hand corner of his mouth and his right eye simultaneously, and said, once more:

"It is in such enlightened means that the bubbling passions of my country find a vent."

As he looked at Martin, and nobody else was by, Martin inclined his head, and said:

"You allude to —?"

"To the Palladium of rational Liberty at home, sir, and the dread of Foreign oppression abroad," returned the gentleman, as he pointed with his cane to an uncommonly dirty newsboy with one eye. "To the Envy of the world, sir, and the leaders of Human Civilization. Let me ask you sir," he added, bringing the ferule of his stick heavily upon the deck with the air of a man who must not be equivocated with, "how do you like my Country?" [Chapter XVI, "Martin Disembarks from That Noble and Fast-Sailing Line-of-the-Packet ship, The Screw, at the Port of New York, in the United States of America. He Makes Some Acquaintances, and Dines at a Boarding-House. The Particulars of Those Transactions," p. 132; running head: "Cross-examined by a Native," 133]

Commentary: Much-vaunted American Democracy and American Myopia

The letterpress's image of "bubbling passions finding vent" is not especially menacing, however, in that it suggests a water geyser such as Old Faithful in Yellowstone National Park rather than an active volcano such as Mount Vesuvius in Italy. No wonder that young Dickens, fresh from his 1842 reading tour of the United States, associates the "rowdy" journalist Colonel Diver with a frothy, bubbly beverage — champagne, of which he has extorted a number of bottles from the captain of "The Screw."

Fred Barnard's first American illustration (discounting the scene of Mark Tapley's comforting his fellow immigrants in steerage) depicts in a close up the arrival of "The Screw" (propeller-driven vessel) in New York harbour in Chapter 16, although the printer has incorrectly placed it in the preceding chapter, when Martin and Mark are still in the middle of the five-week passage. In the letterpress, like diminutive pirates bent upon plunder, a legion of news-boys boards and overruns the packet steamer, hawking wares whose quality and character Dickens makes immediately evident in their satirical titles: the New York Sewer, Stabber, Family Spy, Private Listener, Peeper, Plunderer, Keyhole Reporter, and Rowdy Journal, a scurrilous catalogue that implies the presence of at least eight vendors. However, instead of a milling crowd of miniature entrepreneurs and shipboard customers set against a panorama of docks and ships in America's busiest port, Barnard shows a lone news-boy with a bundle of New York Sewers tucked under his arm. This, indeed, is the very paper to which Dickens in metonymy devotes more than half-a-column: they are all much the same in their partisan prose, accounts of violent incidents, and personal attacks. Barnard sketchily suggests a crowded quay in the background, focusing on Colonel Diver, editor of the Rowdy Journal, in the foreground, centre; he and the newsboy to the right embody the American fifth estate which Dickens vilifies.

Martin has yet to turn and confront the owner of the disembodied, markedly Yankee voice speaking in his ear, so that we cannot evaluate by his facial expression Martin's immediate reaction as his back is towards us and his face to the shore. Thus, Barnard compels us to read the illustration by reading the accompanying letterpress. As Martin turns, he sees what we read: "a sallow gentleman, with sunken cheeks, black hair, small twinkling eyes, and a singular expression . . . which was not a frown, nor a leer, and yet might have been mistaken at first glance for either." Through the narrator's description we can assume that Martin is struck by Colonel Diver's "vulgar cunning and conceit." Although these dubious qualities of Diver's physiognomy are not easily realized in an illustration, Barnard has given us a tall, lean American journalist nattily rather than "shabbily" dress. He is neither the gangly cartoon figure of Phiz's Mr. Jefferson Brick Proposes an Appropriate Sentiment (July 1843), nor the ugly and disreputable American newspaper editor of Dickens's letterpress. To give Diver's words a theatrical referent Barnard has him gesture with his left arm to the news-boy selling The Sewer.

Although his arms are therefore not impressively folded as in Dickens's initial description of him, Colonel Diver's surtout does extend to his ankles, and he does sport a buff waistcoat and a frilled shirt. He casually leans full length against the bulwark of the sailing vessel, and carries exactly the sort of cane Dickens mentions: "shod with a mighty ferule at one end and armed with a great metal knob at the other, [it] depended from a line-and-tassel on his wrist." However, Barnard has markedly reduced the size of the knob, and therefore rendered Colonel Diver far less menacing, as may be more appropriate to the new spirit of Anglo-American co-operation that arose after the Civil War (1861-65).

Relevant Illustrations, 1843-1910

Left: Hablot Knight Browne's satire on seedy New York journalism, Mr. Jefferson Brick Proposes an Appropriate Sentiment (Chapter 16, July 1843). Centre: Harry Furniss's version of Martin's inspection of the newspaper office, "The Rowdy Journal" Office (1910). Right: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s more appreciative treatment of the juvenile newspaper editor, Colonel Diver and Jefferson Brick (1867). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Fred Barnard's realisation of the Martin's meeting Cicero, "You're the pleasantest fellow I have seen yet," said Martin, clapping him on the back, "And give me a better appetite than bitters"(1872). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Dickens, Charles. The Dickens Souvenir Book. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871-1880. The copy of The Dickens Souvenir Book from which these pictures were scanned is in the collection of the Main Library of The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B. C.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman and Hall, 1844.

_____. Martin Chuzzlewit. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1863. Vol. 2 of 4.

_____. Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872. Vol. 2.

_____. Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated Sterling Edition. Illustrated by Hablot K. Browne and Frederick Barnard. Boston: Dana Estes, n. d. [1890s]

_____. Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 7.

Steig, Michael. "From Caricature to Progress: Master Humphrey's Clock and Martin Chuzzlewit." Ch. 3, Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978. Pp. 51-85. [See e-text in Victorian Web.]

Steig, Michael. "Martin Chuzzlewit's Progress by Dickens and Phiz." Dickens Studies Annual 2 (1972): 119-149.

Last modified 22 July 2016

Last updated 19 November 2024