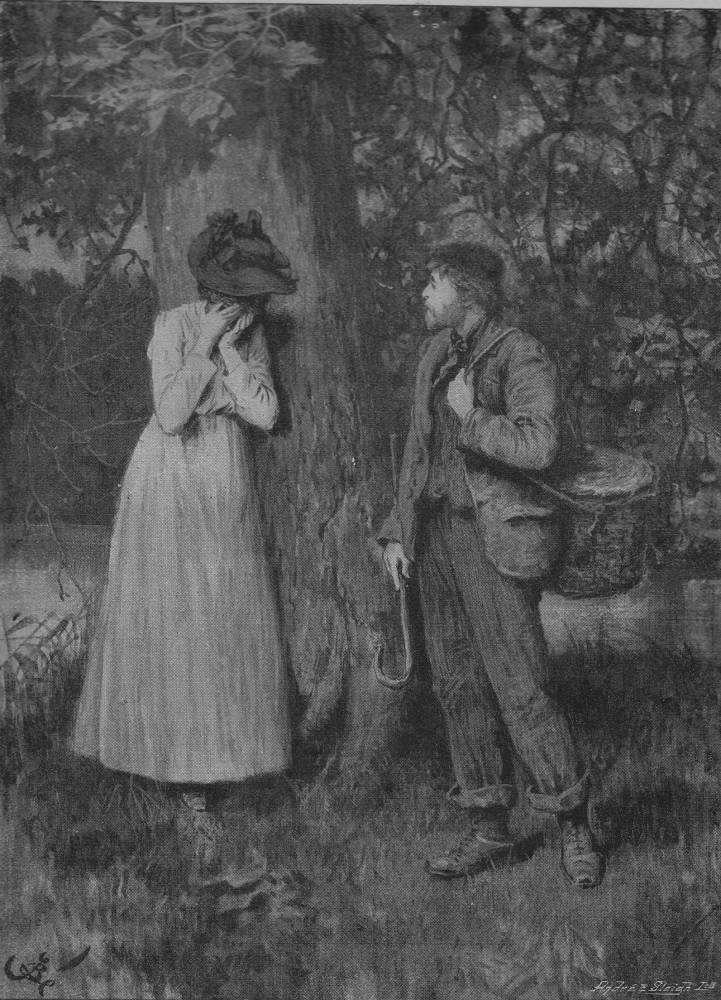

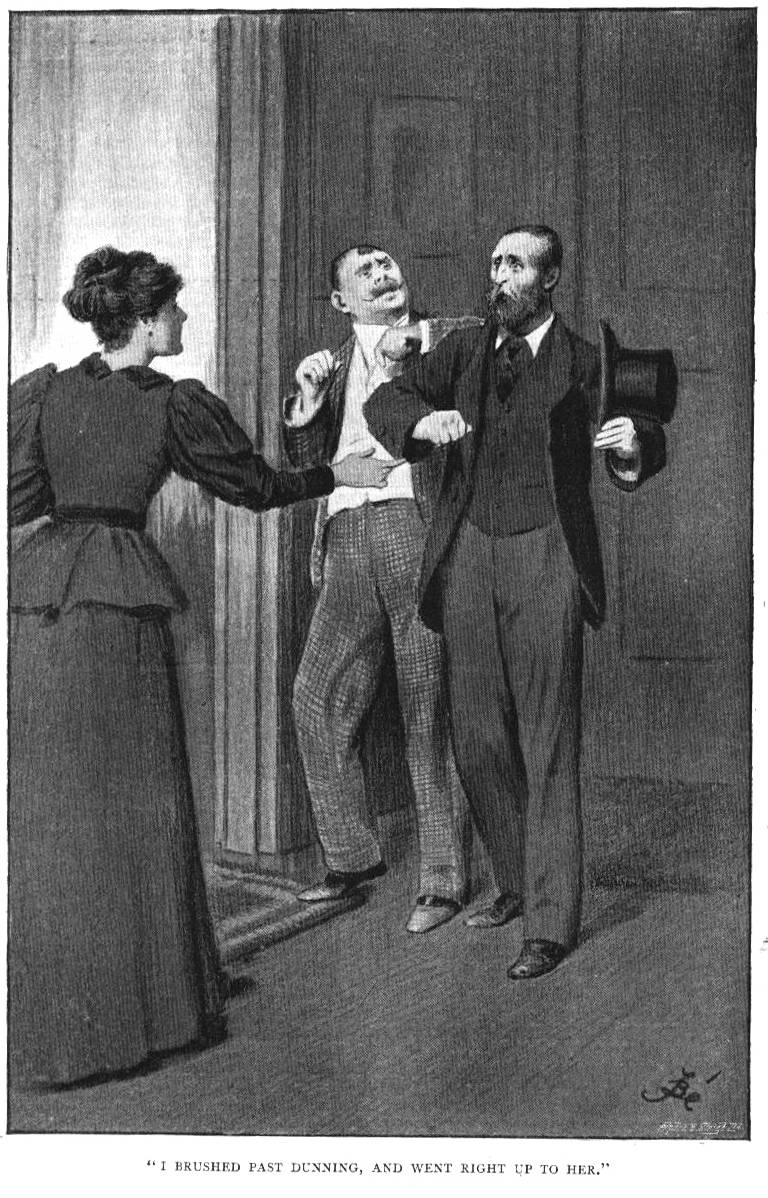

Left: Barnard's October 1895 full-page lithograph for "The Fate of Humphrey Snell" in The Illustrated London News: "It isn't my fault," sobbed the girl. "They've turned me out, and I don't know where to go.". Centre: Barnard's composite woodblock engraving for the same story: "We shall have him on our 'hands" in The English Illustrated Magazine. Right: Barnard's small-scale lithograph for the December 1895 short story "An Inspiration" in The Illustrated English Magazine: "I brushed past Dunning, and went right up to her". [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

When he had become a confirmed writer of short fiction, Gissing never expressed the same inordinate passion for the visual in relation to the verbal that he recognized in Charles Dickens. Although more than two dozen periodical illustrators eventually crossed his path, his lukewarm interest in, if not downright prejudice against, the pictorial rendering of his texts prevented him from interfering or collaborating with most of these artists. [Huguet, p. 26]

The notable exceptions to George Gissing's general antipathy towards magazine illustrators were Amédée Forestier, whose work in The Illustrated London News elevated him above the level of the commercial hack, and Fred Barnard, legendary by the mid-1890s as "The Dickens of Illustrators" for producing some 450 wood-engravings for Dickens's novels in the Household Edition. Prior to 1895, Gissing had appraised the efforts of seven illustrators working on nine of his early short stories. None had pleased Gissing as much as Barnard. Although Barnard's illustrations for "The Fate of Humphrey Snell" in the October number of The English Illustrated Magazine have been available in the Collected Short Stories of George Gissing, his equally fine work for "An Inspiration" in the same magazine is not generally known. Together, these two sets illustrations commissioned by editor Clement Shorter (1857-1926) serve as a fitting tribute to Barnard's interpretive powers in the final year of his life, despite his struggles with depression and opium addiction after the death of his beloved son Geoffrey in December 1891.

Apparently Gissing had no hand in Shorter's selection of Fred Barnard as the illustrator for either story, so that the Barnard illustrations cannot be said to be the result of the sort of collaborative arrangement that existed, for example, between Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz) and Charles Dickens for the serial illustrations of such works as different as The Pickwick Papers (1836) and A Tale of Two Cities (1859). With the rise of magazine fiction late in the century, such truly collaborative relationships were indeed rare. Having had "The Honeymoon" and "Comrades in Arms" indifferently illustrated by house artists Melton Prior and Raye Potter respectively in The English Illustrated Magazine for June and September, 1894, Gissing was pleasantly surprised when he saw "The Fate of Humphrey Snell" in print. The writer commented with delight upon the large-scale illustrations in a letter to Barnard dated September 28, 1895, the story itself about to be published in the October number as the magazine’s lead article:

I really must let you know how very much I am pleased with the full-page drawing you have done for my story in the New English Illustrated. I think it very beautiful, & excellent as a presentment of my thought. It shall be framed for my study-wall, — for indeed the picture is symbolical, & has more significance that the ordinary eye will discover in it. [Letters 6: 33]

Even if the celebrated illustrator of six novels and Forster's Life of Charles Dickens in Chapman and Hall's Household Edition of Dickens's works (1871-1879) sometimes injected humour into scenes where none was warranted, the illustrator of the London sketches of How The Poor Live by George R. Sims (1883) was a natural fit for these early Gissing short stories. With the rise of the illustrated British magazine, the British reading public had come to expect high-quality wood-engravings and lithographs as adjuncts to the fiction, non-fiction, and poetry published in such illustrated periodicals as The Cornhill and Once a Week. For Clement Shorter's monthly magazine, Barnard, both humourist and social realist, strikes exactly the right notes: wistfully romantic and aptly descriptive in "The Fate of Humphrey Snell," and ironic and almost farcical in "An Inspiration." Formally trained at Heatherley's in Newman Street in 1863 (aged 17) and in Paris with Leon Bonnat, Barnard in his magazine and book illustration combines elements of realistic portraiture and caricature admirably suited to Gissing’s social satire. Justifiably, then,

Gissing felt flattered that such a well-known artist should have been recruited for two of his own stories: "a man of less originality than Cruikshank's," he conceded, but who "has done better work in his pictures to the novels [of Dickens in the Household Edition], better in the sense of more truly illustrative. [Charles Dickens: A Critical Study, p. 35; cited in Huguet, p. 26]

Gissing's relationship with Barnard, although hardly collaborative in the sense that Dickens's was with Browne or even Hardy's was with Du Maurier, did involve the exchange of correspondence and even face to face meetings between illustrator and writer. Having completed the novel Eve's Ransom at the end of June, 1894, Gissing had hoped to see the novel serialized that fall under Clement Shorter's editorship in The Illustrated London News. Cryptically in his diary for 4 August 1894, Gissing notes that he "wrote to Barnard with suggestions" (343) for the illustrations for the forthcoming novel. On 17 September, he records that publication of the novel has had to be postponed to the new year "owing to Fred Barnard's breakdown" (348), but the next entry indicates that Barnard is still working on the commission. Evidently, Gissing, disappointed with the quality of Barnard's preliminary sketches for the lithographs, decided to see the illustrator himself on the afternoon of 22 November. Jacob Korg in George Gissing: a Critical Biography notes that Gissing visited Barnard, addicted to alcohol,and laudanum, and therefore unable to continue with so large project as a thirteen-part serialisation. The writer was appalled to discover Barnard living in squalor and poverty, and realized that Shorter would probably have to give another artist the commission. Gissing's diary entry for 22 November 1894 paints the scene most effectively:

In afternoon to see Fred Barnard, at 105 Gloucester Road, Regent's Park. Wretched lodgings; his wife and two daughters in the country, and, I surmise, living at someone else's expense. The poor man very drunk, in a torpor, and only just able to talk connectedly. Has done only one drawing for my story, and the News people are getting very impatient with him. I think it very unlikely that he will finish the job. Looks very young for his age, but has grizzled hair. Subject, I think to delusions; says a man is going about offering forged work in his name. Told me he had got up at 5 that morning (as often) to wander about the streets, but I don’t believe it. He probably used to do so in better days. Talked in melancholy strain of his son (an animal painter) who died at 21. When I left he came out with me, and insisted on drinking brandy at the nearest public-house. [354-55]

The Gissing novel that Barnard had been unable to illustrate appeared in thirteen weekly instalments in the ILN between January and March, 1895, accompanied by illustrations produced by house artist Wal Paget, who had provided that same journal with a sensitive and effective series of twenty-four lithographs for Thomas Hardy's The Pursuit of the Well-Beloved in 1892, 1 October through 17 December. According to F. G. Kitton, Barnard died dramatically in September 1896, not yet fifty, of smoking in bed. Under the influence of "a powerful drug" (222) rather than mere tobacco, his pipe still alight, he fell asleep, and, when the bedclothes caught fire, was suffocated and his body badly charred. Although the circumstances surrounding Barnard's death seem mundane, the details inquest run in the Times reveal a tale of depression and addiction as pathetic as anything in Dickens. But before he died Barnard completed the illustrations for two Gissing short stories to run in The English Illustrated Magazine.

Almost six months after the conclusion of the serial run of Eve's Ransom, Gissing records that Barnard communicated with him again, this time about the full-page illustration for "The Fate of Humphrey Snell": "2 October, 1895 Letter from Barnard promising to give me the orig[inal] drawing of the illust[ratio]n" (390). In fact, Gissing's letters reveal that he was most impressed with Barnard's work for this short story. Undoubtedly reacting to rush proofs, the writer commented with delight upon the twin illustrations in a letter to Barnard dated September 28, 1895, the story itself about to be published in the October number as the magazine’s lead article:

I really must let you know how very much I am pleased with the full-page drawing you have done for my story in the New English Illustrated. I think it very beautiful, & excellent as a presentment of my thought. It shall be framed for my study-wall, — for indeed the picture is symbolical, & has more significance that the ordinary eye will discover in it. (Letters 6: 33)

As visual complements to these Gissing texts the Barnard illustrations achieve effects not apparent in a reading uninformed by an awareness of these realisations; in other words, the reader of a Gissing story in a modern anthology is not likely to be able to construe the story in the way that his or her counterpart of the fin de siecle would have done in that story's original periodical form. Here, Barnard's lithographs and wood-engravings often are so juxtaposed as to sharpen the reader's sense of anticipation (a proleptic reading of the illustration) and awareness of the chief moments in each narrative. Ornamental tailpieces produce a contrasting effect, an analeptic reading informed by a complete reading of the story in advance of encountering the illustration.

Although none of Barnard's seven illustrations for the two stories possesses the comic verve and pointed social criticism of A Meeting of the Parish Council in the November 1894 number of The English Illustrated Magazine, each affects the reading of the story in setting up expectations, consolidating expectations, and commenting on the characters' behaviours. For example, in "We shall have him on our 'hands" (p. 5), Barnard contrasts Humphrey's romantic and somewhat unworldly nature (evident in his encounter with the tearful housemaid in "It isn't my fault") with the mundane, practical, and money-oriented natures of his fleshy father and brother, men of a far more realistic mind-set. As sturdy and unimaginative as the oaken cask on which the older brother, Andrew, sits in Barnard's twin character study, Humphrey's father Thomas and sibling regard Humphrey as a mere encumbrance. Compared to the aesthetic, slender Humphrey, who has rapidly become a denizen of the woods and fields, these other Snells are mere animals. The younger man is but a slighter reflection of the solid elder; the natural milieu of such commonplace thinkers is the public house, a setting which Barnard admirably and economically suggests through the pewter drinking mug (centre) and beer taps (left of centre). In their expressions and postures, as in their pipes, the father and son are reflections of each other.

But perhaps the most significant illustration is the first, in which the artist prepares readers of The English Illustrated Magazine for Humphrey's romantic encounter with the housemaid in the autumnal woods near the mediaeval city of Wells. (Indeed, so effective did Clement Shorter think the full-page lithograph that he arranged for its being reprinted in the 28 September 1895 number of The Illustrated London News.) Although Gissing's narrator remarks early in the story that the bashful protagonist as an adolescent was intimated by young women — "girls, though he sometimes admired them from a distance, always frightened him at close quarters" (4) — the illustration of a languorous beauty leaning against an oak on the opening page (3) alerts the reader to the importance of the protagonist's chance meeting that will lead to Humphrey's destruction. Barnard has correctly assessed, then, the significance of this nocturnal meeting with Annie Frost in the woods (at the bottom of p. 7), and prepares the reader for the scene itself and its consequences (p. 1) this scene at very the outset.

As opposed to the shapely beauty of the headpiece, Barnard gives the reader a tearful maid-servant who is hiding her face in her hands in the painterly lithograph lengthily captioned "'It isn't my fault,' sobbed the girl.'They've turned me out, and I don't know where to go'." Although her clothing and hat as well as the tree trunk provide visual continuity, Barnard introduces an entirely new figure, that of the herb-gatherer Humphrey Snell himself, dressed in fustian and carrying one of those large wicker baskets which he learned to fashion under his relatives the Doggetts in the little Essex village in which the Snells originated. In profile Humphrey in this picture resembles his moustached brother in the illustration on page 3, but he wears an untrimmed beard and cloth cap more suitable to his calling. Although he is hardly disreputable, Humphrey in Barnard’s study wears his pant-cuffs rolled up, and wears a labourer’s neckcloth. Despite his roughness, Barnard’s Humphrey facially has a certain aesthetic delicacy. And Barnard effectively communicates the atmosphere and the setting, the woods at ten on an autumn evening, with its tangle of branches and deep shade. However, Barnard may also be utilizing the realistic tangle of branches (right) symbolically, to foreshadow the romantic snare into which the girl is about to lead him. The specific caption as well as the postures and juxtapositions of the two very different figures point the reader to a specific passage at the top of page 8. Thus, Barnard compels the reader to push on to this significant textual moment, so out of character with the bashful failed postman with whom the story begins.

In the version in The Illustrated London News (28 September 1895, p. 403) the picture on a page of reviews is clearly intended to act as advertisement for the forthcoming October issue of the "English Illustrated." Although the "Literature" page extols a few other "romances" — Max Pemberton's The Little Huguenot (evidently an historical romance in the manner of Bulwer Lytton), Mary Beaumont's A Ringby Lass, and Other Stories ("a pretty little love story concerning a very good young man and an equally good young woman, who quarrel in a hurry and make up at their leisure"), and H. A. Hinkson's Golden Lads and Girls under the heading "Irish Characterisation" — only "The Fate of Humphrey Snell" is complemented by a picture, a large-scale reproduction of a painting which occupies much of the page. Implying that the natural and unspoiled protagonist is a \ species of Wordsworthian leech-gatherer, the reviewer provides a brief synopsis to catch the reader's interest, but does not clearly define Humphrey's "fate":

The October number of this popular magazine opens with one of Mr. George Gissing’s short stories, "The Fate of Humphrey Snell." Humphrey is a child of the woods, a culler of simples, a humble naturalist who earns his livelihood by selling roots to herbalists. The "fate" that comes to him is a girl with a foolish face, and the irruption of this disturbing element into his pastoral existence is very happily described. [403]

One must question Clement Shorter's motives in arranging to have this illustration published in The Illustrated London News just as The English Illustrated Magazine for Octoberwas being published since at first blush doing so would seem a ploy to encourage ILN readers to purchase his magazine in order to appreciate the narrative elements of the picture. On the other hand, Shorter must have felt that the picture could stand as a work of art and be interpreted without benefit of the accompanying text. Certainly, the illustration must have been received as an attractive and compelling advertisement for Shorter's magazine, especially since the reviewer provides similar snippets of romantic deception, political conspiracy, "an ingenious episode of crime," and a mention of another "excellent" illustration, Romney's "Lady Hamilton as Spinstress" (403). Indeed, one suspects that the anonymous reviewer is editor Clement Shorter himself. However, whether because he has mentioned Fred Barnard in the caption for the picture or whether Barnard, a realist of the seventies, was falling out of fashion, the reviewer does not include any analysis of the fine visual accompaniments provided by Barnard for "Humphrey Snell."

Although not by Barnard, the uncaptioned tailpiece seems to function as a visual anti-mask, placing the laughing girl in the midst of an abstract design based upon the woodland vegetation that forms the background in the two illustrations realizing Humphrey's initial meeting with Annie Frost. As opposed to Barnard's characterization of the housemaid as the sexual force which, like Jude Fawley's atavistic desire for Arabella in Thomas Hardy's Jude the Obscure, seals Humphrey's tragic fate, in the ornamental tailpiece by Ada Clegg a strong wind blows the girl's unbound hair to the right. Suggestive of the pains and pleasures of a romantic relationship, leaves and thorns encircle the female form whose clinging dress is decorated with berries. All of this is a visual complement to the closing lines of the story, in which the narrator equates the adolescent symbol for kisses ("a row of crosses," p. 10) with a grave-marker, implying that Humphrey's yielding to the unfamiliar and unruly passion will ruin him and break his spirit. Oblivious to the pain she causes, the self-confident girl laughs at the ease with which she has deluded and robbed her dreamy, gullible swain.

A more humorous and light-hearted tale of love thwarted and then realised is Gissing's "An Inspiration," a vehicle more congenial to Barnard's talents as a visual satirist. To ensure that the reader focuses on the character of the commercial traveller Laurence Nangle (identified by his sample bag), rather than his Fairy Godfather, Harvey Munden, Barnard features a portrait of the shy salesman in the headpiece. The same scantily bearded figure appears the table from his confidant, "the finger of Providence," in the restaurant scene, "He selected a cigar with fastidious appreciation," a humorous detail suggestive of Nangle's social incompetence being his wearing his hat indoors. Finally, in the penultimate illustration, Nangle triumphantly elbows a surprised James Dunning aside to make his romantic appeal directly to the wealthy widow in "I brushed past Dunning, and went right up to her" (p. 274) on the page facing the passage, telegraphing to the astute magazine reader the story's climax in advance of his actually reading it.

Illustrations: A. "The Fate of Humphrey Snell," by Fred Barnard

- "It isn't my fault," sobbed the girl. "They've turned me out, and I don't know where to go." (p. 403 in The Illustrated London News), 19 cm by 14.1 cm (lithograph).

- Untitled headpiece, p. 3 in The English Illustrated Magazine; 8 cm by 13 cm (lithograph).

- "We shall have him on our 'hands" (p. 5); 15 cm by 11.2 cm (wood-engraving).

- 4. Uncaptioned tailpiece, p. 10; 5.4 cm by 6.9 cm (wood-engraving).

B. "An Inspiration," by Fred Barnard

- Uncaptioned headpiece of the protagonist, p. 268; 7.4 cm by 12 cm (wood-engraving)

- "He selected a cigar with fastidious appreciation" (p. 271); vertically mounted, full-page, 12.4 cm by 18.2 cm (wood-engraving)

- "I brushed past Dunning, and went right up to her" (p. 274); 19.1 cm by 12.6 cm (lithograph)

- Uncaptioned tailpiece, p. 275; 2.1 cm by 7.4 cm

Bibliography

Barnard, Fred. "A Meeting of the Parish Council." The English Illustrated Magazine. Vol. 12 (November 1894): 84.

Coustillas, Pierre, ed. London and the Life of Literature in Late Victorian England: The Diary of George Gissing, Novelist. Hassocks: Harvester Press; Lewisburg: Bucknell U. P., 1978.

Gissing, George. Charles Dickens: A Critical Study. Ed. Simon J. James. Grayswood: Grayswood Press, 2004.

_______. "The Fate of Humphrey Snell." The English Illustrated Magazine. No. 145 (Oct., 1895): 1-10.

_______. "An Inspiration." The English Illustrated Magazine. No. 147 (Dec., 1895): 268-75.

Houfe, Simon. "Barnard, Fred." The Dictionary of 19th Century British Book Illustrators. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Antique Collerctors' Club, 1978, revised 1996. Pp. 53-54.

Huguet, Christine, ed. Spellbound, George Gissing. Volume One: The Storyteller. London: Equilibris, 2008.

Korgin, Jacob. George Gissing: a Critical Biography. London: Methuen, 1965.

"Literature: The 'English Illustrated'." The Illustrated London News. 28 September 1895. Page 403.

Mattheisen, Paul F. Arthur C. Young, and Pierre Coustillas. The Collected Letters of George Gissing. 9 vols. Athens, OH; Ohio U. P., 1990-97.

Created 4 July 2013

Last modified 24 January 2021