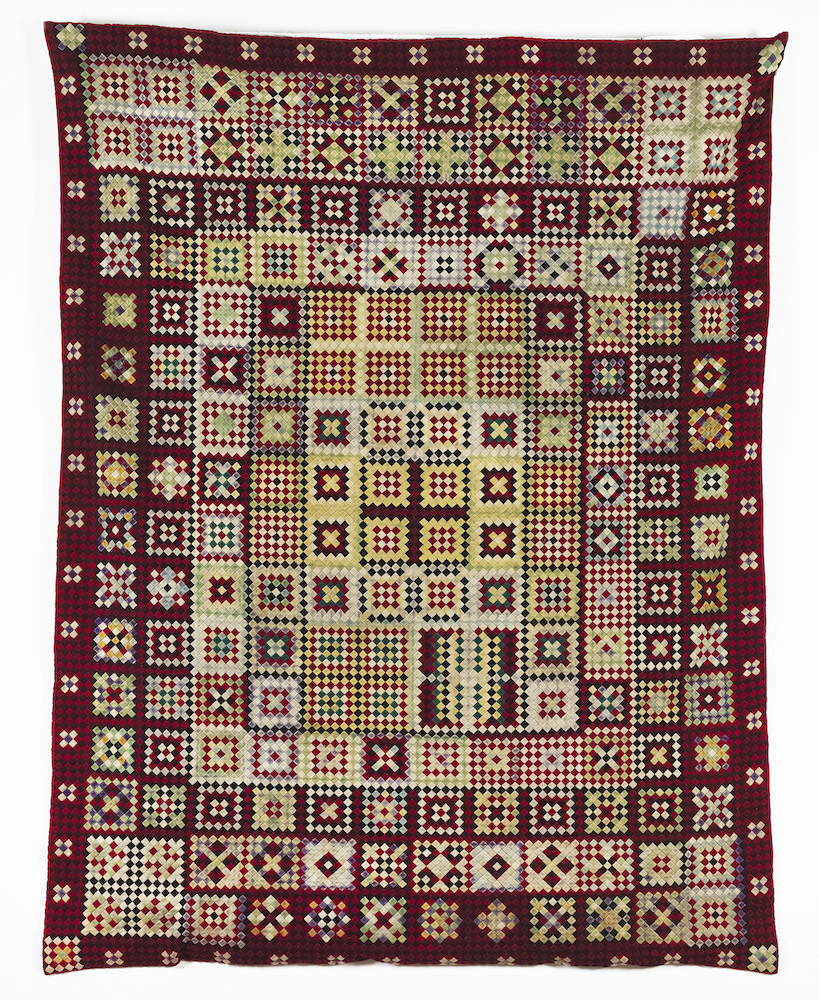

The nineteenth century was the great quilt age in Europe and America — pieced block quilts were an American innovation, as was the radiant work of the Amish and Mennonite communities. In Great Britain, wholecloth quilts, medallion patches, all-over patches worked with paper templates, and strippy quilts were the most prevalent. Exuberant use was made of tailors’ samples and cotton manufacturers’ sprigged and floral scraps. It was a time of quilting-bees, parties and frolics, when the country population would gather together and make one or more quilts in an afternoon. These were sociable occasions, and welcomed in a rural community where the local church was often the only meeting place. They were a chance for women to meet away from the confines of the house, while still doing something "useful." Quilting and other forms of craft were outlets for artistic expression that cut across social boundaries, Money, education and refinement are irrelevant where a pleasing design is concerned. The disdained and maligned utility quilt made from old work-shirts can be quite as handsome as any fussy concatenation of thousands of minute postage stamps of dissonant silks stitched by ladies of leisure. — Miranda Innes pp. 12-13

Men also had a role in piecing and designing quilts in Britain. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the role of the limner was very important — to ladies of the noble households, for he it was who composed their designs and drew them out on cloth. In the nineteenth century, George Gardiner, a shopkeeper in Northumberland, performed the same function for the local women who wanted a quilt top marked for working. The idea that an artist was essential to embroidery or quilt design was also embraced in the Art Needlework movement of the nineteenth century: women were advised to use the services of an artist if they could not themselves draw, or even to go to the Royal School of Art Needlework in London, where they could borrow designs that had already been worked. One supporter of the Art Needlework movement, Lewis Day, even went so far as to suggest that women were incapable of designing: they should do the stitchery, he said, and leave the designing to the men! It has to be acknowledged, however, that some mem proved equally adept with the needle. Pieced table covers and inlay work ... were a highlight of the Great Exhibition of 1851 and many of these entries were by men. Soldiers, sailors and tailors also seemed particularly attracted by the challenge of intricate piecing. — Janet Rae, p. 10

Works

Bibliography

Audin, Heather. Patchwork and Quilting in Britain. Botley, Oxford: Shire, 2013.

Innes, Miranda. Rags to Rainbows: . London: Collins & Brown, 1993.

Rae, Janet. The Quilts of the British Isles. London: Constable, 1987.

Created 17 November 2023

Last modified 18 November 2025