A Note by William Morris on His Aims in Founding the Kelmscott Press

William Morris, 1834-96, printer designer

1898

20.8 x 14.6 cm.

Beckwith, Victorian Bibliomania catalogue no. 21

After William Morris died in 1896, his trustees and friends published this book as the last work of the Kelmscott Press. It is a memorial and an essential history of Morris's development as a designer concerned with every aspect of book production. The volume begins with an account written by Morris for a London bookseller who had an American client desirous of giving a lecture on the Kelmscott Press. [Continued below]

Click on image to enlarge it, and mouse over text below to find links

You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Internet Archive and University of Maryland and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Commentary by Alice H. R. H. Beckwith

With an audience of bibliomaniacs and printers in mind, Morris wrote a detailed description of his aims and design process, including his type, paper, ink, and employees. Appended to Morris's essay are Sidney Carlyle Cockerell's chronicle of Morris's interest in book design from 1866 to 1896; sample pages of the Golden, Troy, and Chaucer types; and an annotated list of the books printed at Kelmscott. Cockerell later gained an international reputation as a scholar of the history of books, eventually becoming Keeper of Manuscripts at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

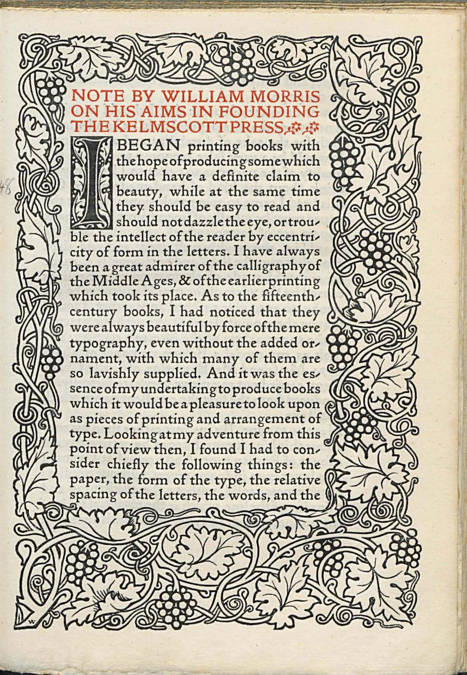

Analysis of the content and form of page 1 of A Note reveals that it is a microcosm of Morris's ideas and achievements. Motivated by a desire to create something beautiful for the mind and the eye, Morris reports that he approached the art of bookmaking informed by the scribal arts of the Middle Ages and the typography of incunabula (books printed before 1500). The works he chose to print were selected for their noble intellectual content, and he named his types after the books for which he planned them.

A Note is set in Golden type, the first of the three types he designed. "Golden" derives from The Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine. It is a roman form based on the fonts used by Jacobus Rubeus in his 1476 printing of Leonardo of Arezzo's History of Florence and in Nicolas Jenson's Pliny of the same date (Cockerell, ll). Using photographs to enlarge the letters in Rubeus's and Jenson's incunabula, Morris created the Golden type in 1891. His use of photography and electrotype castings of illuminated initial letters, borders, and marginal ornaments belies the regressive, anti-technological attitude sometimes attributed to him.

Fruiting grapevines and their leaves are found in William Blake's illuminated Job (cat. 1), as well as in Renaissance, medieval, and ancient Roman decorative arts. Morris took here an ornamental form used by artists of the past and gave it a new life by redesigning it. His folded broad leaves recall the thirteenth-century illuminated manuscripts from England he admired and owned, such as the Pierpont Morgan Psalter (cat. 20). Furthermore, these leaves illustrate how Morris incorporated medieval influences within classical and Renaissance motifs. This border is signed W in the lower left corner. It and the illuminated initial I are among the 644 designs for Kelmscott books Morris drew over the course of the press's seven-year history.

To plunge his readers directly into the matter at hand, Morris often dispensed with traditional title pages, half titles, and introductions, choosing simply to state the title above the text. Here it is set off by being printed in capitals and red ink followed by two printers' flowers or fleurons. This rubrication echoes medieval practice, and was also employed by fifteenth-century printers. Even though A Note was not designed by Morris himself, his procedures were followed.

Morris's combination of aesthetic and intellectual authority continued to influence printing in Europe and the United States long after his death. The types he designed continued to be available, but the present volume was the last book in which Morris's own ornaments were used. Following his last wishes Morris's trustees destroyed the electrotypes and placed the original woodblocks for his ornaments on deposit in the British Museum until 1996, one hundred years after his death.

References

Beckwith, Alice H. R. H. Victorian Bibliomania: The Illuminated Book in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Exhibition catalogue. Providence. Rhode Island: Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, 1987.

.

Morris, William. A Note by William Morris on His Aims in Founding the Kelmscott Press, and a Short Description of the Press by S. C. Cockerell, and an Annotated List of Books Printed Thereat. Hammersmith: Trustees of William Morris, 1898. Printer: Kelmscott Press. Internet Archive version of a copy in the library of the University of Maryland, College Park. Web. 21 December 2013. [In the 1987 exhibition the copy came from the John Hay Library, Brown Universary.]

Victorian

Web

Decorative

Arts

Victorian

Bibliomania

William

Morris

Next

Last modified 21 December 2013