[Click on thumbnails for larger images and additional information]

The mid-Victorian period was characterized by a massive expansion in publishing. The ever improving literacy of the middle-class audience created a market for reading that was satisfied by the mass production of an extraordinary range of books and periodicals. One of the most interesting genres was the Christmas gift book. Usually published at the end of November, though post-dated so it could be sold the next year as well, this product was solely intended as a cadeau, a precious object to be given to a spouse, a family member, or sweet-heart.

The emphasis on what I have elsewhere defined as giftness (Cooke 121) had important implications for the books' content and appearance. First and foremost, it meant they were designedly low-key in terms of their textual content. According to contemporaries, the publication was only supposed to be a piece of bland entertainment, a branch of 'legitimate manufacture' which would please the recipient when he or she opened it up on Christmas morning. In the urbane words of an anonymous critic in The Saturday Review (1866), 'Nobody expects or wishes for originality, or depth, or learning in a Christmas book. Hallam or Grote or Milman or Darwin is not what a Christmas book is made of...(653). Like consumables produced to create a passing sensation, the gift-book was viewed as an 'elegant' trifle, a 'pretty' but superficial artefact which continued the Keepsake and Annual traditions of the thirties and forties.

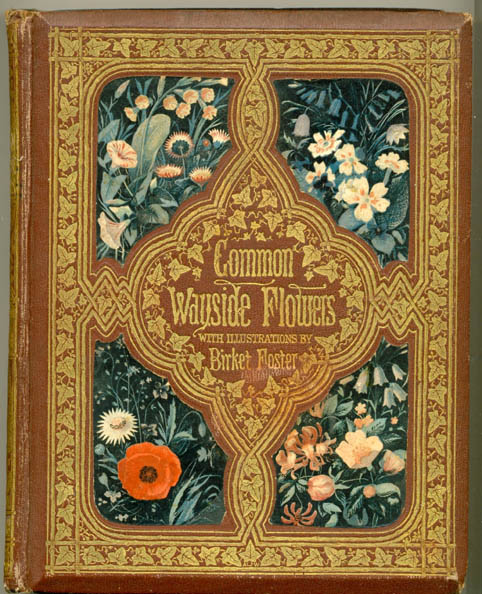

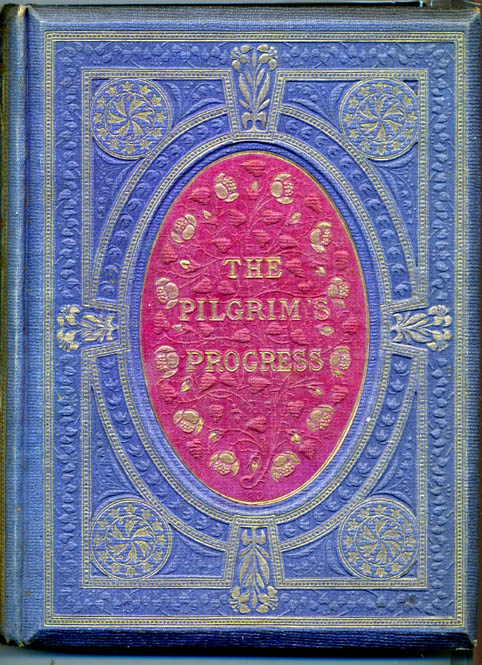

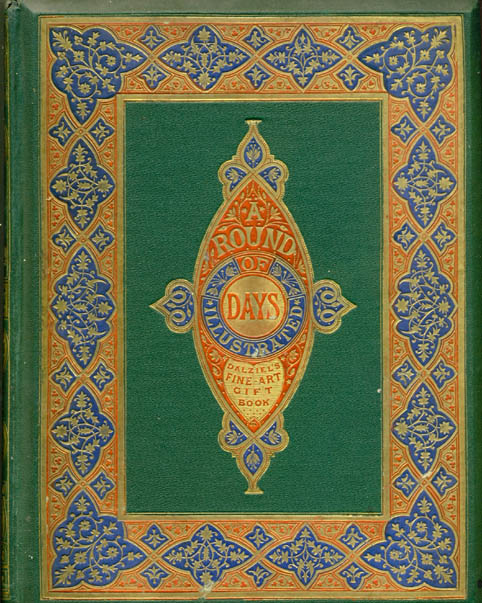

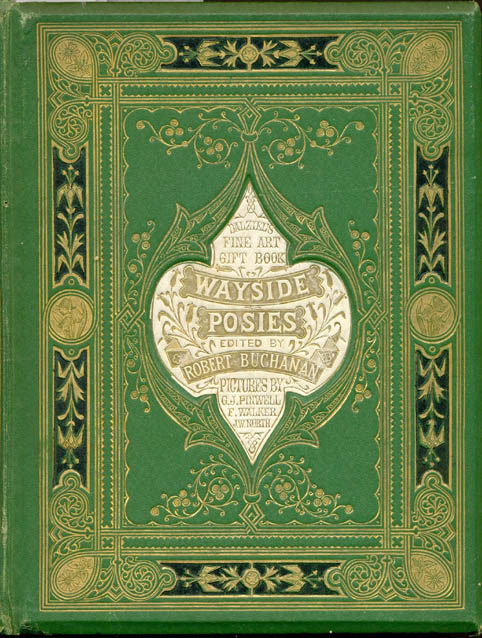

This credo of calculated superficiality translated into an emphasis on undemanding verse, usually in the form of anthologies such as A Round of Days (1866), re-prints of hymns and prayers, and other material of a sentimental, domestic or pious nature. At the same time, there was a strong emphasis on visual splendour: the written texts were sometimes conventional and uninspired, but the illustrations operated in another register entirely. Indeed, gift books of the Sixties contain some of the most accomplished black and white designs of the period. Furnished by artists such as Millais, Pinwell, Walker, Houghton and Birket Foster, they were intended to be looked at, rather than read, and their gilt-edged pages undoubtedly provided many hours of contented viewing by the fireside, both at Christmas time and into the New Year.

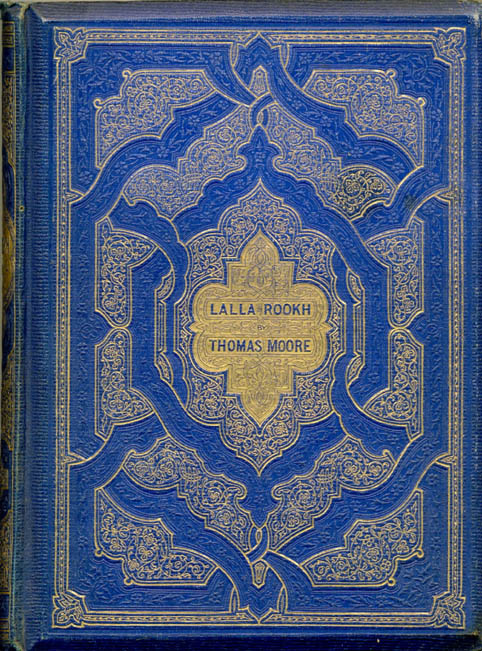

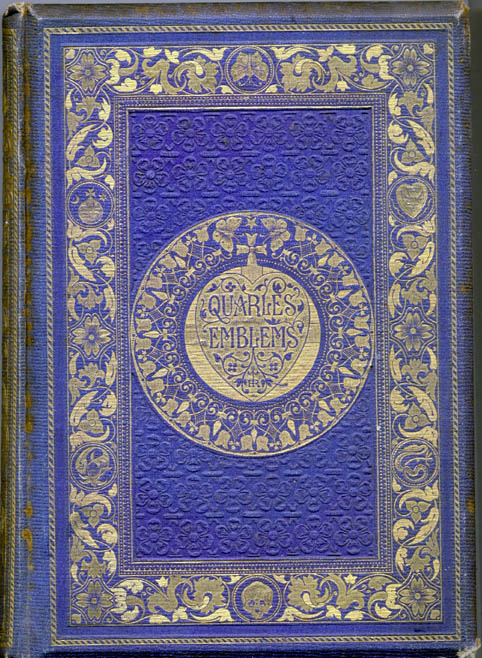

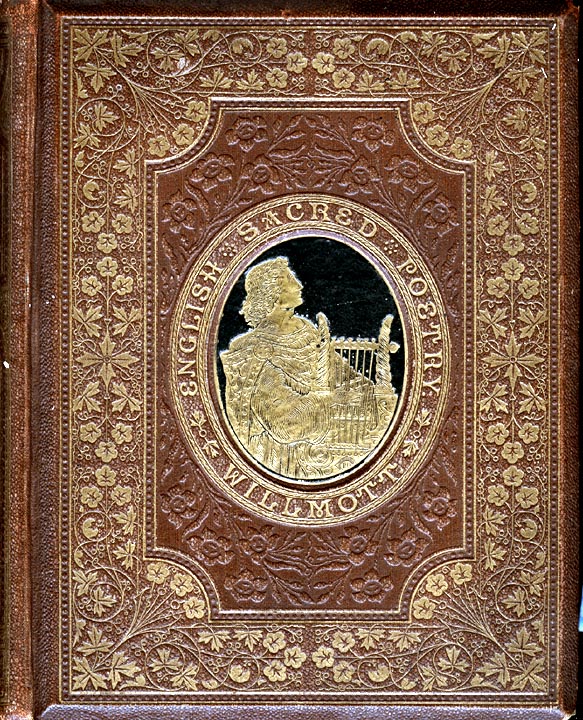

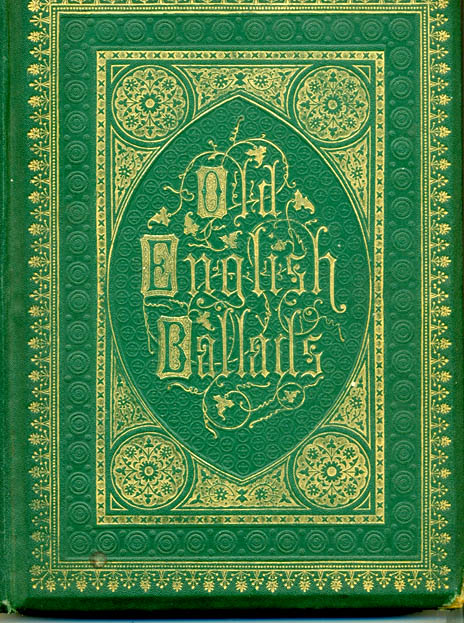

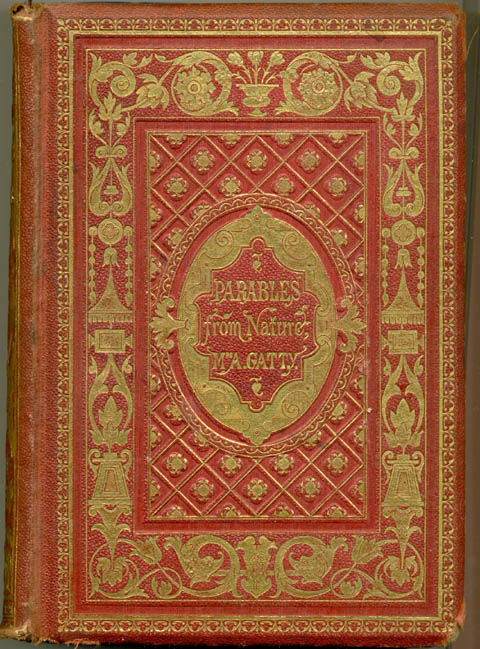

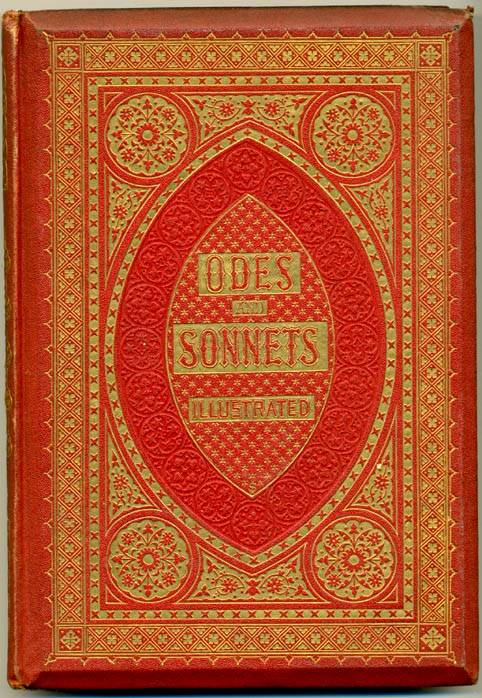

But the books' most striking characteristic was their elaborate bindings. Described by Edmund King in his encyclopaedic Victorian Decorated Trade Bindings (2003), these outer casings are emblematic products of mid-Victorian culture. Typified by coloured cloth, embossed surfaces and elaborate gilt and polychromatic paper overlays, the bindings are fascinating examples of the intersection between bourgeois taste, the visual encoding of the values of Christmas, and industrial production. Design histories of the period note how ostentation was favoured by bourgeois consumers because it expresses middle-class wealth, and there can be no doubt that Christmas books appear to be expensive and luxurious items. Based on the elaborate bindings that middle-class readers thought they might find in some idealized aristocratic library, they emulate the displays of opulence supposedly favoured by those at the top of the social ladder. Yet gift books were entirely the product of industrial processes: no handicraft, beyond the initial design, was involved, and the bindings were entirely produced using machines, industrial products such as gutta percha gum and its substitutes, and machine production. Typically costing between fifteen shillings and a guinea, they represent the middle-class reader's desire to emulate his 'betters' while keeping a close rein on their expenses. Christmas gift books were in this sense another aspect of the process of democratization in which a bourgeois audience aspired to social improvement and self-expression by gaining access to what pretended to be fine goods.

Such judgements seem to condemn them to the status of ersatz, and in their own time they were routinely condemned for their vulgarity, shallowness, and emphasis on display. Yet Christmas gift books do have value beyond their significance as historical artefacts. As noted above, their illustrations are typically of a very high quality, among the very best of their period; and the same appreciation can be made of the bindings. Although mass-produced, these were designed by some outstanding individuals. The foremost contributor was John Leighton (1822-1912), who designed an unknown number of casings, perhaps more than eight hundred. Others include Albert Warren (1830-1911); John Sleigh (active 1841-72); Robert Dudley (active 1858-91); and Harry Rogers (1825-74). Each developed distinctive styles, usually signing their work in tiny gilt initials. Details are given in the analyses of Ball (1983) and King (2003), although the most penetrating commentary, which contains an astute investigation of individual styles, is provided by Sybille Pantazzi (1961 & 1963).

References

Anon. 'Christmas Books'. The Saturday Review 24 November 1866: 653.

A Round of Days. London: Routledge, 1866.

Ball, Douglas. Victorian Publishers' Bindings .London: The Library Association,1985.

Cooke, Simon. 'Illustrated Gift Books of the 1860s'. The Private Library 5th Series 6:3 (Autumn 2003): 118-138.

King, Edmund. Victorian Decorated trade Bindings, 1830-1880. London: The British Library & Oak Knoll Press, 2003.

Pantazzi, Sybille. 'Four Designers of English Publishers' Bindings, 1850-1880'. Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America55 (1961): 88-99.

Pantazzi, Sybille. 'John Leighton, 1822-1912: a Versatile Victorian Designer'. Connoisseur152 (April 1963): 263-73.

Further Reading

- Tom Kinsella's bibliography on his review of King's Victorian Decorated trade Bindings, 1830-1880

Last modified 8 August 2010