n the Victorian era, gloves were deeply connected to the notion of the "perfect hand" which were to be "shapely, finely made, and white, with blue veins, taper fingers, and rosy nails, slightly arched” (Beaujot, 31). They were therefore seen as social markers. Accordingly, ladies wore gloves which were too small for them in order to shrink their hands. Their goal was to avoid the thickness and coarseness of working-class women's hands. Gloves were also used to take care of hands, so at night women slept with old gloves filled with various skin-improving recipes found in magazines, advice manuals, and encyclopaedias. These creams could be made with ingredients women already had at home like soap, buttermilk, lemon juice, vinegar, rainwater, rosewater, glycerin, horseradish or oatmeal. Commercially made recipes were also advertised in women's magazines. They were promoted as healthy but in reality, they were dangerous as they often contained lead and arsenic.

Types of Victorian Gloves: Length, Colour, Material and Decoration

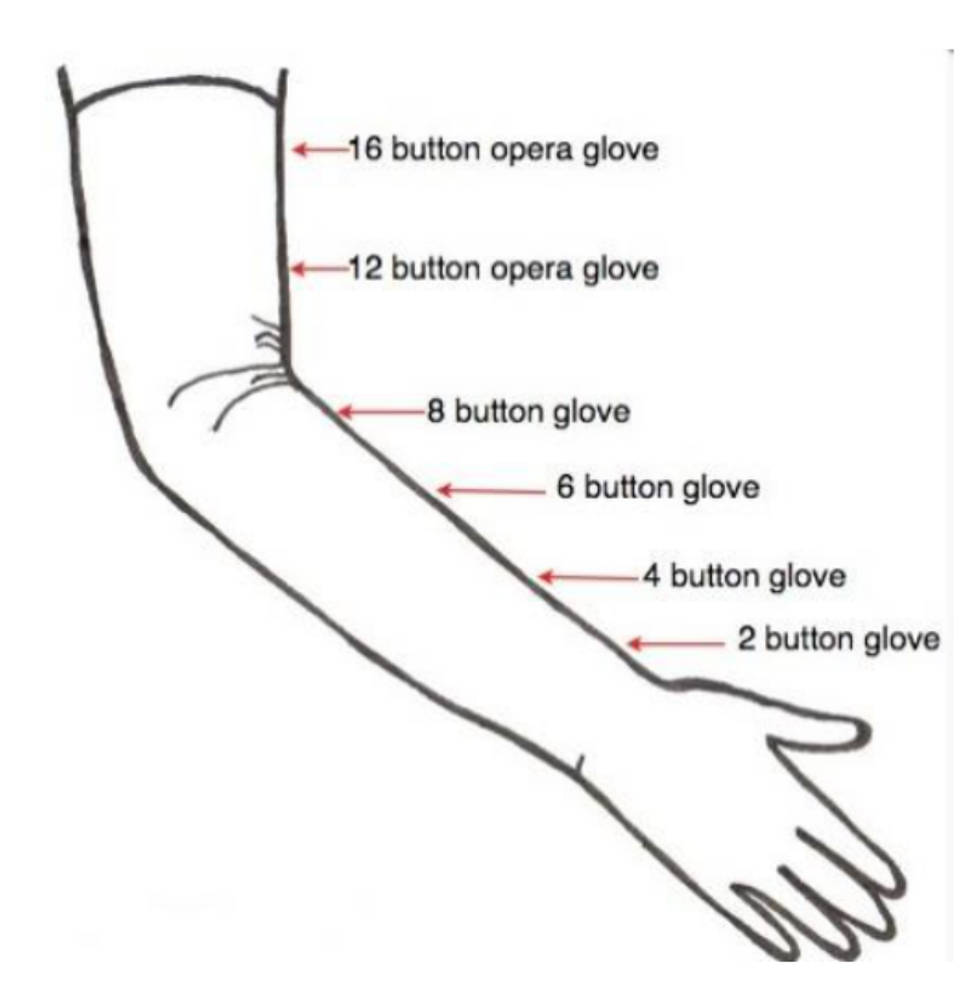

Following an old French practice, glove length was traditionally measured in buttons based on the distance between the base of the thumb and the top edge of the glove. Until just before before Queen Victoria's reign, gloves were quite short. Fashion changed after 1835, as gloves started being worn half-way between wrist and elbow, and their length kept increasing throughout the century. Gloves were usually made of white kid, but pale colours like pink and yellow were also worn. Short kid gloves continued to be fashionable for daytime wear during the 1850s and early 1860s. They were fastened at the wrist with two to four buttons. In 1865, short gloves for evening attire were no longer fashionable and were replaced by long gloves — from four to six buttons — called “opera gloves”. Evening gloves continued to get longer and longer, reaching half-way to the elbow during the 1870s and going beyond it in the 1880s. This kind of glove could be fastened with up to twenty buttons. After 1865, daytime gloves also grew longer. Until the end of the century, their length varied from covering the wrist to half-way to the elbow. However, they would never again be worn as short as at the beginning of Queen Victoria's reign.

At all periods, kid leather was used for gloves because it was seen as fashionable and luxurious. Throughout the century wealthy women also wore silk and cotton gloves for informal or country wear rather than fashionable attire.

A replica of Queen Victoria's coronation gloves made of white kid, edged and lined in deep purple satin and gold scallop-patterned bobbin lace threaded with large sequins. The upper hand applied with embroidered blue and red badge bearing the motto Honi Soit Qui Mal Y Pense, below red velvet Queenly crown, 35 cm long. Machine sewn between 1870 and 1876. Source: The Worshipful Company of Glovers' of London. Accession No: 25744

Silk mittens often served as major Victorian accessories, though they were only fashionable during the 1830s and ’40s, and they later came back into fashion at the end of the century.

Gloves and Everyday Life: Habits and Conventions

The requirements of etiquette which was subject to changing fashion followed clear guidelines and were defined by what was called prescriptive literature. Women read handbooks defining good and bad manners in order to achieve a certain standard as wives and mothers, but also as ladies. Accordingly, if a woman mastered these social codes, she would be considered “a proper lady” (Beaujot 35-36). On the contrary, if a woman could not afford to submit to these rules, her femininity would be brought into question and her importance in society discredited. It was common not to wear gloves within the domestic sphere - for example when having dinner or tea at home. On the contrary, it was considered inappropriate for a woman to go outside without her gloves on, as ungloved hands were sometimes associated with nudity. For a man to remove a woman's glove was seen as “an erotic and physical stand-in for the act of sex itself” (Blakemore). When invited to a dinner party or any event, women wore gloves but removed them during the meal. Throughout the century, both ladies and gentlemen were required to wear white kid gloves when ‘in full dress’. Regarding balls, it was imperative to never dance without gloves.

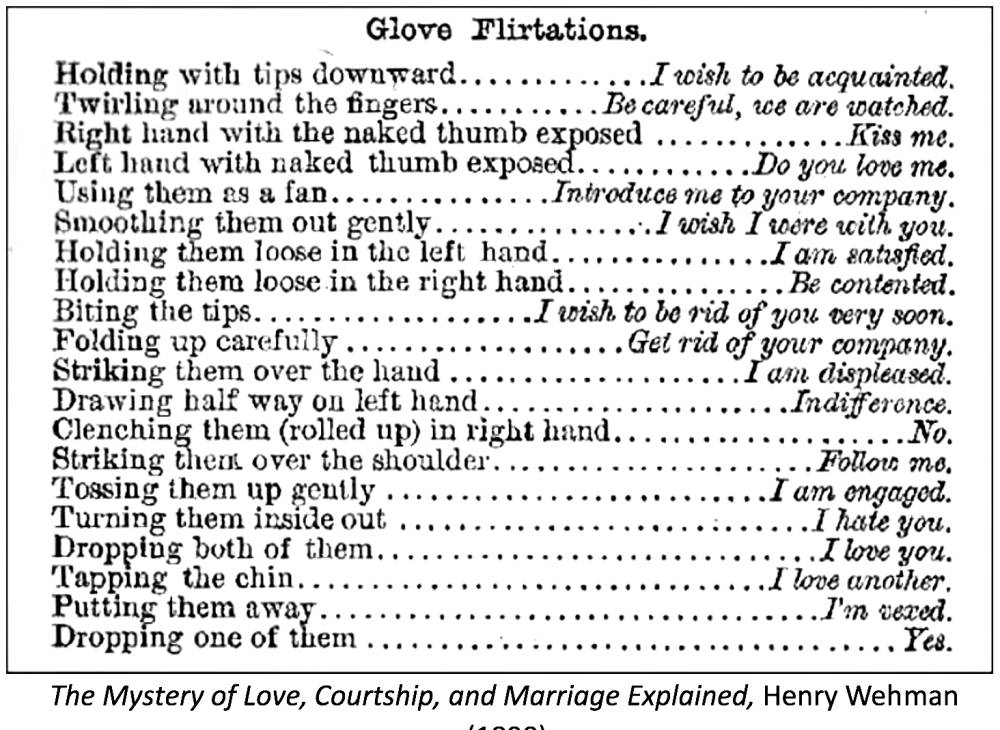

Glove etiquette was also used to express untold feelings, whether positive or negative, in a discrete and tactful way. In 1890, Henry Wehman presented his interpretation and analysis of the glove language:

Gloves could also be part of a game, as covering hands and forearms with gloves was the equivalent of covering one's face with a mask. Victorian ladies could use fashion accessories to play a role and as such, gloves were used as a disguise, for the creation of a character. Glove etiquette was closely associated with social class, as it applied only to women who could afford to follow the glove conventions. For example, it was required for a lady to change her pair of gloves several times a day, which lower class women obviously could not afford to do. Moreover, the visible darnings on the gloves of working-class women were only reminders of their inability to keep up with the conventions, as a proper lady would buy a new pair of gloves instead of mending damaged ones. Gloves were carefully cleaned and kept in ornate glove boxes but also perfumed in order to mask any unpleasant odours. It was also a very private accessory as it covered what was considered an intimate part of women's bodies. For example, when Queen Victoria had to lend her gloves to her half-sister on June 25th 1838, she considered the incident so unusual that she mentioned it in her journal, with two exclamation marks: ‘Dear Feodore dressed in my room; and, none of her things being come, she was obliged to wear one of my dresses, my stockings and shoes and gloves!!’ (Queen Victoria, 78) This remark shows how intimate gloves were as Queen Victoria seemed to feel uncomfortable sharing them, even with her half-sister.

Gloves in Victorian Literature and Art

In the Victorian era, when gloves were often seen as a symbol of a woman’s purity, painting and literature sometimes used them to define the moral character of protagonists. For example, in Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations Miss Skiffins who refuses any physical contact with Wemmick until they are married, is the embodiement of purity. Accordingly, the author makes a point of highlighting the fact that she always wears gloves: “While Miss Skiffins was taking off her bonnet (she retained her green gloves during the evening as an outward and visible sign that there was company)” (525). She also wears a different type of gloves to show that she is engaged : “That discreet damsel was attired as usual, except that she was now engaged in substituting for her green kid gloves, a pair of white.” Here, the white colour emphasises her purity.

In contrast, William Holman Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience uses a glove to suggest a woman’s lost innocence. The painting, which depicts a woman standing up from her lover's lap, shows his glove upon the floor symbolizing of her lost innocence and her social deterioration. The glove, which is a crystal-clear symbol of the etiquette and good manners, has here become neglected as it fell on the floor. And the fact it is thrown on the floor highlights the lady's loss of purity, as virtue was discarded, like the accessory itself.

In conclusion, we can say that gloves were both an empowering and enslaving device. Accordingly, wearing fine and sophisticated gloves provided a way for members of the middle classes to show their respectability and for the upper classes to display their wealth and power. Gloves also defined womanhood, since respecting conventions, such as wearing the proper kind of gloves, was perceived as being ladylike. When she writes that ‘the glove is a tyrant of which the hand is a slave’ (34), Ariel Beaujot metaphorically describes a relation of coercion that also applies to Victorian etiquette and to the Victorians.

Bibliography

Beaujot, Ariel. Victorian Fashion Accessories. Oxford: Berg, 2012.

Blakemore, Erin. “What Gloves Meant to the Victorians.” JSTOR Daily. 24 Feb. 2018, Accessed 10 April 2019.

Day, Charles William. Hints on Etiquette and the Usages of Society: With a Glance at Bad Habits. Boston: W.D. Ticknor, 1844.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. London: Chapman and Hall, 1861.

Etiquette for Ladies and Gentlemen. London: Frederick Warne & Co, 1876.

Victoria, Queen. Queen Victoria's 20th journal. British Library, 1832-1838.

Walton, Geri. “Glove Etiquette in the 1800s.” Unique histories from the 18th and 19th centuries. 19 June 2014.

Wehman, Henry. The Mystery of Love, Courtship, and Marriage Explained. New York: Wehman Bros, 1890.

Last modified 30 October 2019