St Luke's Church, Chelsea. James Savage (1779-1852). 1820-24. Bath stone. Sydney Street, Chelsea, London SW3. Photographs by the author and George P. Landow 2010/11. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL or cite it in a print one. Click on the images to enlarge them]

Four views of St. Luke's Church under clouds and in sunshine: (a) West front and main entrance. (b) East end. (c) Three-quarter view from east end. (d) View of across Chelsea rooftops of St. Luke's from the ninth floor of a building on Sloane Avenue, showing how the church dominated the skyline before the construction of twentieth-century buildings.

St Luke's is an imposing church, built for a congregation of 2,500, visible from every angle and from upper-storey windows far and wide. The "biggest and tallest parish church in London," with a nave that was then higher than that any other London church barring St Paul's or Westminster Abbey, it is often seen as "Chelsea's Cathedral" (Johnston 1). It also has a special place in the history of the Gothic Revival. Charles Lock Eastlake considered it in some ways typically pre-Puginesque, pointing out that its "rigid formality" was very much of its time (141), but he noted too such Gothic elements as the window tracery, the turrets and pinnacles at the top of the tower, and the flying buttresses. Features like these surprised people at a time when the Gothic style was largely the province of country house architects. Indeed, Clare Johnston points out that when Savage drew up his plans, "[t]he functional masonry of flying buttresses and stone vaulting was to be attempted for the first time in over 300 years" (3). However, Savage's work was clearly transitional,, and Eastlake is scathing about the final effect: "the prominent blunders in this design are an unfortunate lack of proportion, a culpable clumsiness of detail, and a foolish, overstrained balance of parts." He cites "the lanky arches of the west porch, with their abrupt ogival hood moulding," the unvaried buttresses, the identical windows, the regular intervals of the string courses, and the crude masonry: "large blocks of stone are used in uninterrupted courses, scarcely varying in height from base to parapet." These flaws, he claimed,

combine not only to deprive the building of scale, but to give it a cold and machine made look. In a far different spirit the Mediaeval designers worked. Their buttresses were stepped in unequal lengths, the set-offs becoming more frequent and more accentuated towards the foundation. Their string courses were introduced as leading lines in the design, and were not ruled in with the accuracy of an account book; their windows were large or small as best befitted the requirements of internal lighting; their walls were coursed irregularly, the smaller stones being used for broad surfaces, and the larger ones reserved for quoins and the jambs of doors and windows. (142)

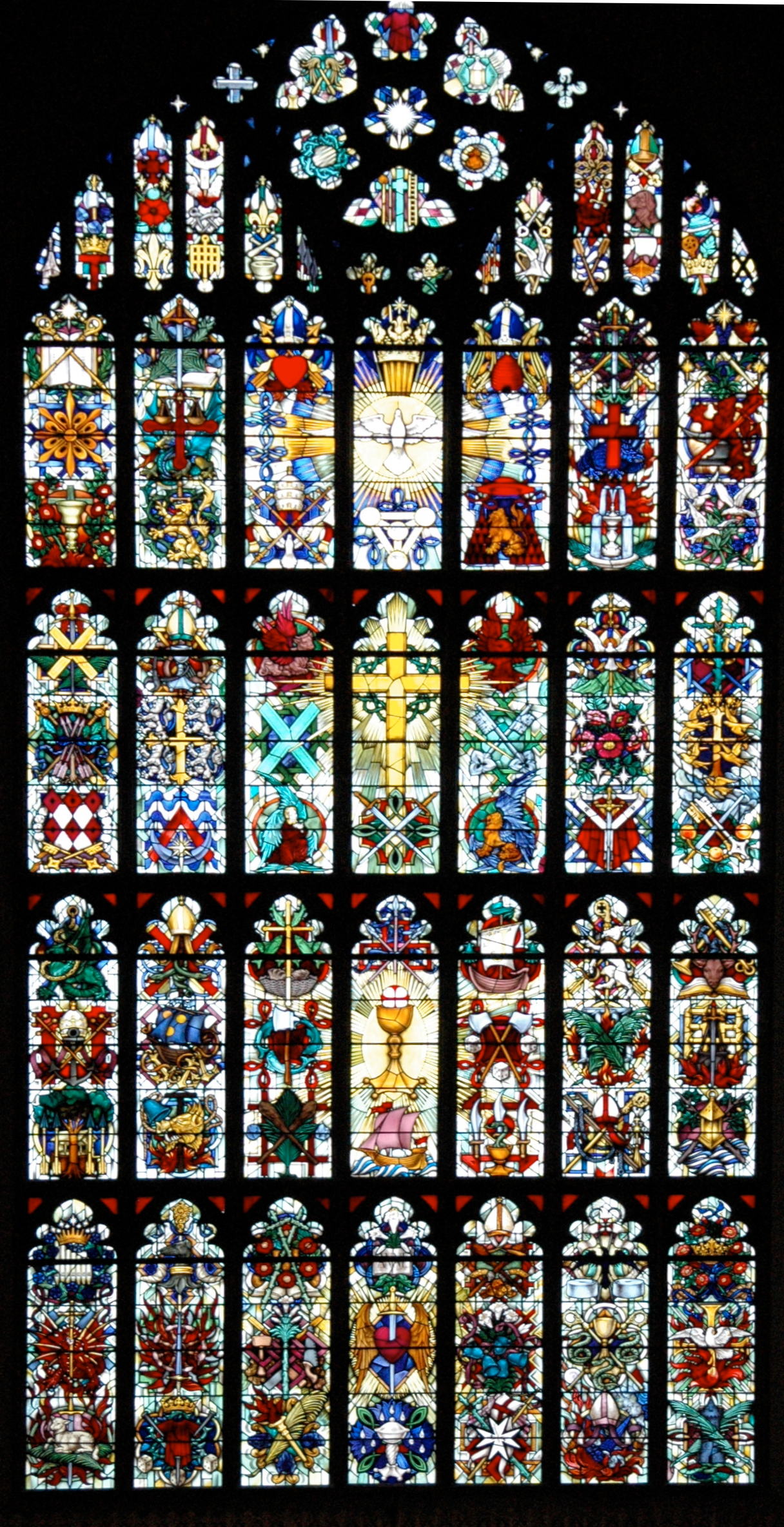

Left to right: (a) The nave, looking towards the chancel. (b) Closer view of the chancel. The altarpiece, designed like a Gothic screen, is by Savage himself, while the central painting of 1823 is by James Northcote, and depicts the Entombment. (c) The vast east window, filled with stained glass by Hugh Easton (1906-65), showing the emblems of many saints around and beneath syymbolic representations of Jesus and the Trinity. Northcote's original window was destroyed during the London air-raids. (d) The organ. Its case mostly dates back to the original one designed by Savage, incorporating "the likeness of the church tower into its facade" (Johnston 14). Notice the arms of George IV, carved in mahogany. The church has wonderful acoustics and a fine musical tradition.

Was Savage's dull uniformity the result of lack of inventiveness, Eastlake wonders, or of adhering to contemporary proprieties? Whatever the cause, the result, he felt, was a lack of picturesqueness and grace. It is fascinating to see him on the one hand acknowledging that the church was pre-Puginesque, and on the other hand panning it from a post-Puginesque perspective. His remarks about its "crude vulgarity of detail" also illuminate what was so special about Pugin and his disciples:

no one who examines with attention the character — if character it may be called — of the carved work [in St Luke's], can fail to perceive the absence of vitality it exhibits in the crockets and finials which are supposed to adorn its walls. No educated stone carver employed on decorative features would care to reproduce the actual forms of natural vegetation for such a purpose, but in his conventional representation of such forms he would take pains to suggest the vigour and individuality of his model. Fifty years ago this principle was almost ignored. There was naturalistic carving, and there was ornamental carving ; but the noble abstractive treatment which should find a middle place between them, and which was one of the glories of ancient art, had still to be revived. (142-3)

In light of later developments, then, Savage's church falls short, and Eastlake was unable to appreciate its solidity, its loft, its "taut, dramatic outline" (Johnston 5), or even the elegance that comes from streamlining. However, he did recognise some of its individual attractions. He says that the "upper part of the tower, though foolishly over-panelled, is good in its general proportion," and he has a few kind words too for "the octagonal turrets at the east end." He particularly approves of the "groining of the nave," which he finds "all the more remarkable, when we remember the wretched shams by which such work was then too frequently burlesqued." He has fainter praise for the reredos ("for its date, by no means contemptible"), and graciously excuses the galleries on the grounds that many later churches continued to incorporate them when their architects should have known better (143-4)!

Left to right: (a) Elegance in the ceiling of a side aisle. (b) More fine carving on the churchwardens' stalls at the west end. (c) Late Victorian sentimentality: cherub's head and floral pattern on the stone stem of the pulpit, which replaced the original wooden one — the octagonal marble font of 1826 is simpler and more dignified.

St. Luke's Church — literary and other associations

A facsimile of Dickens's wedding certificate, on display at the west end.

As well as being one of the very earliest neo-Gothic churches built in London, and certainly the most prominent amongst them, St Luke's has always had an important place in the community. It was a large site, for which Savage also designed new parish schools in the neo-Gothic style, with a high pointed central arch and two tall houses on either side, for the Boys' School Master and the Girls' School Mistress. These were constructed in 1824-26 (only the central archway remains now, the buildings having been replaced by a parish hall and private houses). It was, all in all, "a large and active Evangelical parish" (Vance). Among the well-known Victorians associated with it were Charles Kingsley, whose father was the Rector there from 1836-60; Charles Dickens, who married Catherine Hogarth here on 2nd April 1836; local artist Walter Greaves, who was baptised here in 1846; and Jerome K. Jerome, who got married here in 1888. Its first organist, John Goss (1800-80), composed the music for "Praise, my soul, the King of Heaven." A further link with the past is established by the badges and colours in the Piffer (Punjab Frontier Force) memorial chapel in the south aisle (see below), where the battle-worn colours carried by the 2nd Punjab Infantry throughout the Indian Mutiny/War of Independence of 1856/7 are on display.

Additional views

Sources

Church of St Luke, Chelsea. British Listed Buildings. Web. 6 Jan. 2011.

Eastlake, Charles L. A History of the Gothic Revival. London: Longmans, Green, 1872. Internet Archive. Web. 6 Jan. 2011.

Johnston, Clare. A Guide to St Luke's Church, Chelsea. London: St Luke's Church, 1999.

Vance, Norman. "Kingsley, Charles (1817-1875)" (father of the novelist). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 6 Jan. 2011.

Last modified 6 January 2011