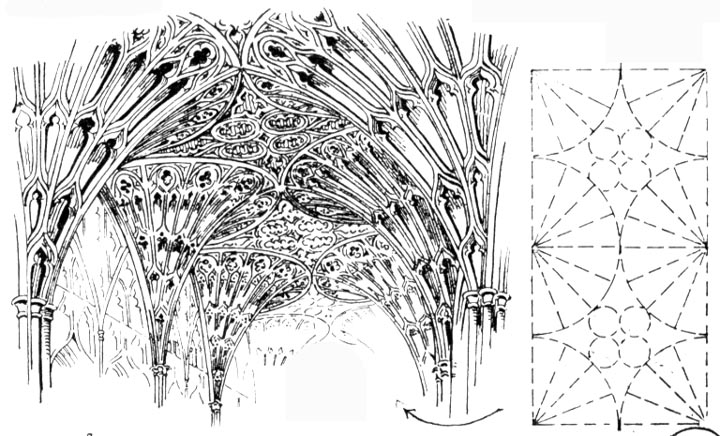

Fan Vaulting, Gloucester Cathedral. Drawn by Banister Fletcher for A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method (5th ed), plate 112 (p. 285). Scanned image and text by George P. Landow (2007) [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The complicated "stellar" vaulting of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries led, by a succession of trials and phases, to a peculiarly English type of vaulting in this century known as fan, palm or conoidal vaulting, in which the main ribs, forming equal angles with each other and being all the same curvdture, are formed on the surface of an inverted concave cone, and connected at different heights by horizontal lierne ribs.

The development was somewhat as follows: — In the thirteenth century the form of an inverted four-sided hollow rectangular pyramid was the shape given to the vault. In the fourteenth century the masons converted this shape, by the introduction of more ribs, into a polygonal (hexagonal) pyramid, as in S. Sepulchre, Holborn, and elsewhere. In the fifteenth century the setting out of the vault was much simplified by the introduction of what is generally known as "Fan " vaulting, described above).

Owing to the reduction of the size of panels, due to the increase in the number of the ribs, a return was made to the Roman method of vault construction, for in fan vaulting the whole vault was often constructed in jointed masonry, the panels being sunk in the soffit of the stone forming the vault instead of being separate stones resting on the backs of the ribs. The solid method seems to have been adopted first in the crown of the vaults where the ribs were most numerous. In some "perpendicular" vaults the two Systems are found, as at King's College Chapel, Cambridge; in others, as Henry VII.'s Chapel, Westminster, the whole vault is of jointed masonry.

The difficulty of supporting the flat lozenge-shaped space in the top portion of the vault surrounded by the upper boundaries of the hollow cones was comparatively easy in the cloisters, where this type of vaulting was first introduced, because the vaulting spaces to be roofed were square or nearly so, but when it was attempted to apply it to the bays of the nave, which were generally twice as long transversely as longitudinally, difficulties occurred. In King's College Chapel (A.D. 1513) the conoid was continued to the centre, but the sides were cut off, thus forming an awkward junction transversely. In the nave of Henry VII.'s Chapel pendants supported by internal arches were placed away from the walls and the conoids supported on these, thus reducing the size of the flat central space, and changing it from an oblong to a square on plan. At Oxford Cathedral a somewhat similar method was adopted, the pendants also placed some distance from the wall, being supported on an upper arch, and a polygonal form of ribs adhered to.

Fan vaulting is confined to England, and other examples beyond those already mentioned are in the Divinity Schools, Oxford; Trinity Church, Ely; Gloucester Cathedral (see illustration above); S. George's Chapel, Windsor; the retro-choir, Peterborough, and elsewhere.

References

Fletcher, Banister, and Banister F. Fletcher. A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method for the Student, Craftsman, and Amateur. 5th ed. London: B. T. Batsford, 1905.

Last modified 30 August 2007