Biography

James Brooks (1825-1901) was a former Vice-President of the RIBA who received its Gold Medal for Architecture whilst in office. He was a prolific and influential High Church Gothic Revivalist. Although he is far less widely known now than some of his contemporaries, like George Gilbert Scott and G. E. Street, his work is still much praised by important architectural historians. In his hands, says James Stevens Curl, "the Gothic became Sublime in its aesthetic" (108).

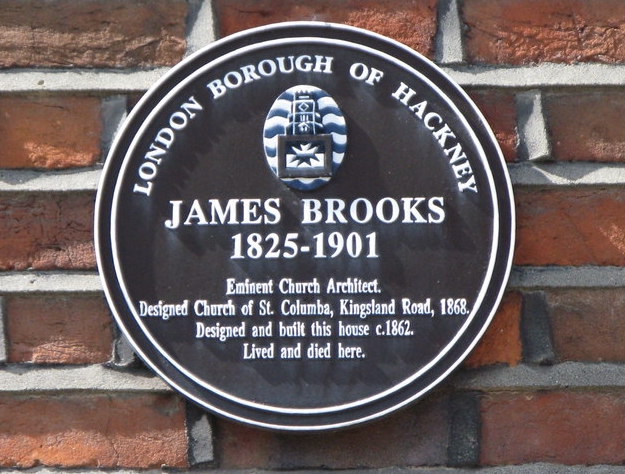

Brooks was the son of a gentleman farmer in Hatford in Berkshire. His family later moved to Wantage in Oxfordshire, where he attended the nearby long-established Abingdon School. His earliest interest and success was in agricultural technology, and he retained a lifelong love of hunting and shooting. Nevertheless, he gravitated to London, where he trained under the architect Lewis Stride, and was inspired by T. L. Donaldson's lectures at University College. He enrolled in the Antique School of the Royal Academy in April 1849, and set up in independent practice in Bloomsbury in 1852 or so (see Adkins 494, 505). He got married around five years later and in 1862 he and his family moved into The Grange in Stoke Newington, a rather grand five-bedroomed house of his own design, with three reception rooms, "ample domestic offices," and a garden ("Sales by Auction"). The house, at 42, Clissold Crescent, London N16, now has a plaque commemorating him as an "Eminent Church Architect" ("James Brooks").

Left: No. 42 Clissold Crescent, once The Grange (somewhat altered but still with a very impressive entrance). Right:

Brooks soon made his mark. His work was recognised for its "boldness of style, combined with unusual solidity" ("Mr Brooks's Churches"), and his hugely impressive London churches should have established his reputation for many years to come. As a committed High Churchman, serving in lay capacities at his local churches in Stoke Newington, he was driven by a sense of mission. The places of worship he designed were landmark churches for the East End, in Shoreditch, Haggerston, Hoxton and Plaistow: "With their wide, lofty naves, narrow aisles, raised chancels, and lancet or plate-traceried windows, these noble and beautifully proportioned buildings epitomize the mid-Victorian ideal of the Anglican town church" (Tyack). He also designed the churches' related clergy and school buildings, including, in a couple of cases, convents for Anglican sisters. In fact, Curl calls him "perhaps the greatest of the designers of complexes for 'town churches'" (108). While the East End churches had to be economically built, with the architect himself collecting funds for such work (see Adkins 508), he had more scope for embellishment in better-off areas of London such as Kensington and Hammersmith.

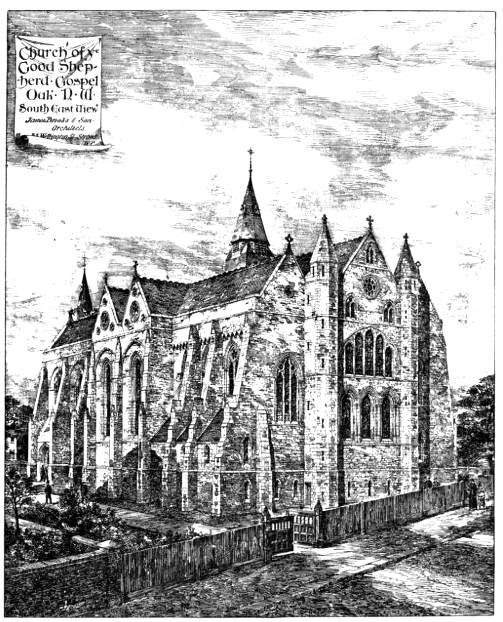

Church of the Good Shepherd, Gospel Oak.

Brooks was elected as a fellow of RIBA in 1866, and held several important positions. He became honorary consulting architect to the Incorporated Church Building Society in 1880; a member of the RIBA council in 1881; diocesan architect for Canterbury in 1888; and, as mentioned above, Vice-President of the RIBA. That was in 1892. On 24 June 1895, while still serving in that capacity, he was formally presented with the RIBA gold medal for distinguished work in architecture. He might perhaps have been knighted had he not courted disapproval by marrying his housekeeper after the death of his first wife (see Tyack).

Brooks's health deteriorated and in 1876 he died of heart failure at home at The Grange. His eldest son James Martin Brooks (1859-1903), whom he had taken into partnership by then, carried on his architectural practice in partnership with his other pupil, George Godsall. But both died within a few years, Godsall in 1905. James Brooks's assistant, John Standen Adkins (b. 1859), who wrote a long memoir of Brooks in the RIBA Journal, then completed some of the work that was still unfinished.

Ken Allinson describes Brooks as a "typically forgotten RIBA Gold Medal winner" (233), but he gets high praise not only from Curl but also from a whole range of architectural historians who agree that "Brooks's work is the supreme example of the aesthetic of the Sublime in Victorian church architecture" (Dixon and Muthesius (217); that individual churches like St John the Baptist, Holland Road (1872-89) are impressively "noble and lofty" (Cherry and Pevsner 454); and that he was among the influential "famous London names" of church architecture in the Victorian period (Saint 10). — Jacqueline Banerjee

Works

- The Grange, Stoke Newington (his own home, see above)

- St Andrew, Plaistow

- The Church of the Good Shepherd, Gospel Oak

- St John the Baptist, Holland Road, Kensington

- All Hallows, Gospel Oak: I (Exterior)

- All Hallows, Gospel Oak: II (Interior)

- All Hallows, Gospel Oak: III (Fittings)

Bibliography

Academy Architecture and Architectural Review. Ed. Alexander Koch. London: Academy Architecture, 1895. Internet Archive version of a copy in the University of Toronto libraries. Web. 15 May 2015.

Adkins, J. S. "James Brooks: A Memoir." R.I.B.A. Journal. 17 (23 April 1909): 493–516 (see Appendix A for a list of his principal works).

Allinson, Kenneth. Architects and Architecture of London. Oxford: Elsevier, 2006. Note: Allinson says Brooks was born in Hatfield, which is in Hertfordshire. Other sources are more trustworthy here.

"The Architectural Association." Times, 12 October 1901: 11. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 15 May 2015.

Cherry, Bridget, and Nikolaus Pevsner. London 3: North West. London: Penguin, 1991.

Curl, James Stevens. Victorian Architecture. Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1990.

Dixon, R. Life and Work of James Brooks, 1825–1901. Ph.D. thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 1976.

"James Brooks." London Remembers. Web. 28 December 2024.

"List Entry" (for St John the Baptist, Holland Road). Historic England. Web. 14 May 2015.

"Mr Brooks's Churches." Architecture, Vol. 4. 20 August 1870: 108. Google Books. Free Ebook. Web. 15 May 2015.

Saint, Andrew. "The Late Victorian Church." The Victorian Society Studies in Architecture and Design, Volume Three: Churches 1870-1914. Ed. Teresa Sladen and Andrew Saint. London 2011. 7-25.

"Sales By Auction." Times, 10 February 1902: 16. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 15 May 2015.

Sheppard, F. H. W., ed. "The Holland Estate: Since 1874." Survey of London: Volume 37, Northern Kensington. London, 1973: pp. 126-150. British History Online. Web. 15 May 2015.

Tyack, Geoffrey. "Brooks, James (1825–1901), architect." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 15 May 2015.

Created 15 May 2015

Last modified 28 December 2024