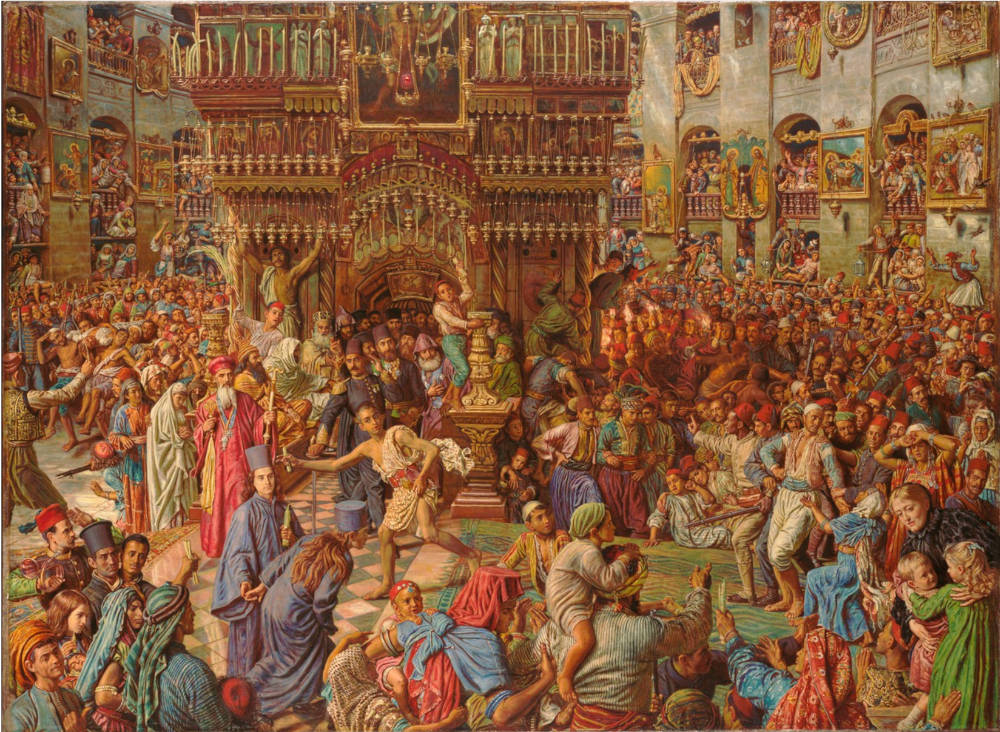

William Holman Hunt. The Miracle of the Holy Fire. 1896-69. Oil on canvas, 36 1/4 x 39 1/4 in. Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

In additon to thus possessing obvious relations to Hunt's The Light of the World and Christ the Pilot, The Importunate Neighbour also demands comparison with The Miracle of the Holy Fire in the Church of the Sepulchre at Jerusalem (1893-99), another picture that derives from Hunt's last visit to the Middle East. This work, like The Importunate Neighbour, concerns man's attempt to encounter the divine, and just as The Light of the World was what Hunt termed the "mystical" version of the realistic Awakening Conscience, so The Importunate Neighbour stands as a mystical or visionary version of this realistically depicted representation of the Greek Orthodox Easter Eve rite in Jerusalem.

As I have argued elsewhere, The Miracle (or Distribution) of the Holy Fire uneasily combines a Hogarthian satire on the evils of superstition with the artist's desire to capture an exotic bit of ethnographic, anthropological, and historical fact. This late work, which is pictorially unusual because it depicts a crowd scene, bears a slight resemblance to Edward Poynter's Israel in Egypt (1867) and The Visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon (1890) or to William P. Frith's Derby Day (1851), Ramsgate Sands (1862), and Private View of the Royal Academy, 1881 (1883). I suspect that Hunt was less influenced by these works or the similar crowd scenes of Makart, Doré, and Couture than by the work of Hogarth. If I am correct, the major reason Hunt produced a work that divides into groups of hard, often static figures lies in his attempt to achieve the satirist's emphasis — an emphasis which requires each individual part to stand out. In other words, attempting to follow the lead of Hogarth's satiric prints made him succumb to that early Pre-Raphaelite tendency of accumulating disparate, disunified elements, a tendency for which the critics of the 1860s attacked him.

For Hunt the Easter Eve ritual represented the degeneration of authentic religious wonder into selfishness, superstition, and worse — into mad frenzy and unchristian violence. During the ceremony the Greek Patriarch of Jerusalem produced a candle supposedly lit by heavenly powers or angelic visitation. For the painter his picture of this rite had a specific topical reference. It was his response to those ecumenically minded Anglicans who proposed in the late 1870's and eighties to join with Greek, Armenian, Russian, and other Orthodox churches. As the painter wrote to J. L. Tupper in 1877, "How Stanley can desire union for our Church with the Greek perpetrators of miraculous fire I can't understand." [ALS May Is, 1877; Huntington Library MS]. By the time Hunt came to paint this scene representing institutionalized superstition, much of its topicality had been lost, but it still bore important meanings for the artist, since it satirized established, conventional Christianity. Hunt's inclusion of detailed descriptions of mob violence in the catalogue prepared for the painting's first exhibition in 1899 emphasizes his view of such religious lunacy. Furthermore, employing the Hogarthian device of the visual pun, he also included "in the pediment of the frame the seven-branch candlestick as a symbol of religious truth for the illumination of the people, which instead of giving light is negligently left to emit smoke, thereby spreading darkness and concealing the stars of Heaven" [Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, 2 vols., London, 190s, ll, 385; this entire paragraph quoted from my 1979 book on Hunt.].

This symbolic candelabrum makes clear that the scene taking place within its confines shows that when men seek material versions of holy illumination and holy inspiration, they only extinguish God's true fires. Like Tennyson's "The Holy Grail," The Miracle of the Holy Fire demonstrates that when men seek a cheap and easy road to salvation, they inevitably put out the divine light within themselves.

This same candelabrum appears above the doorway at which the figure in The Importunate Neighbour pleads, thus permitting us to compare the two paintings on several grounds. First of all, this illustration of a parable presents an individual, rather than an institution or organized assembly of people, striving to reach God, and this emphasis is entirely in keeping with Hunt's intensely individual version of Protestant Christianity. For him, as for so many Victorians, belief comes as a subjective, personal, unprovable fact and is destroyed inevitably by institutionalization. Second, The Importunate Neighbour, unlike The Miracle of the Holy Fire, places its pleading figure, who represents the true condition of all humanity before God, in a night setting — a setting that, one assumes, the painter expected to be understood as symbolizing man's darkened condition and hence his essential need for divine illumination, for precisely that kind of illumination men strive for so desperately, so profanely, in the Easter Eve ritual. Third, The Importunate Neighbour, unlike the other painting, seems to suggest man's proper attitude toward God — one of humble supplication in which the believer can do little more than simply open himself to the divine. Rituals, arrogance at possessing the truth, attempts to find material proof of spiritual matters, all snuff out the divine light.

Shadows Cast by the Light of the World: William Holman Hunt's Religious Paintings, 1893-1905

[This article originally appeared in The Art Bulletin, 65 (1983), 471-84.]

- Introduction

- Christ the Pilot

- The Importunate Neighbour

- The Beloved

- Hunt's Themes of Conversion and Illumination Throughout His Career

Created 2001; last modified 3 August 2015