Click on all the images to enlarge them, and, in Parts IV and V, to find more information about them.

andscape art — that is, art that treats the natural scene as a subject in itself, rather than as part of a composition — is a fairly recent phenomenon. Kenneth Clark surmises that the art of classical antiquity had been too "deeply rooted in the Greek sense of human values" for the natural world to play anything other than a "subordinate part" in it. "Only the Odysseus series in the Vatican," he continues, "suggests that landscape had become a means of poetical expression, and even these are backgrounds, digressions, like the landscapes in the Odyssey itself" (1). Still, these distant views, these backdrops to human activities in classical art, were at least a starting point.

I: Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin

Left: Claude's Pastoral Landscape, 1645. Credit: The Henry Barber Trust, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham. Right: Poussin's Landscape with Travellers Resting (A Roman Road), 1648. By permission of Dulwich Picture Gallery.

In continental Europe, landscape first assumed importance in the seventeenth century, and in two areas: in the Mediterranean countries, and in the Netherlands. From the Mediterranean countries came the carefully composed, classically inspired works of Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) and Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665) — specifically in their paintings for the royal retreat of Philip IV of Spain. "Claude produced Landscape with an Anchorite and Poussin Landscape with St Jerome. The mix of these two types of rural scene and human subject, shepherds and anchorites and their deliberate association, in a lavish commissioning exercise, with the Buen Retiro ideal of civilized retreat, confirmed the new status of landscape art" (Andrews 51). These works were commissioned in the 1630s, and both artists went on to produce other paintings in which the "rural scene" was prominent. Examples, shown above, are Claude's Pastoral Landscape of 1645, and Poussin's scene of a Landscape with Travellers Resting (A Roman Road) of 1648. The former shows cows and sheep, a meandering river and distant mountains. On the right is a ridge crowned by a castle, on the left, a tall tree shades a small group of countryfolk. The delicate play of light and shade, perhaps in late afternoon light, is part of the overall harmony of the scene, which certainly allows landscape to predominate. Poussin's scene is livelier, with more (and more varied) human activity, but again perfectly balanced, with deeper shadows across the road, and a more dramatic sky. An orange tree calls attention to itself on the left, making a group on this side to match with the trees and church on the other. There is an implication here of life as an onward journey, despite the two people resting on the right.

II: Richard Wilson

Two paintings by Richard Wilson. Left: View of Tivoli: The Cascatelle and the "Villa of Maecenas", c. 1752. By permission of Dulwich Picture Gallery. Right: Lyn-y-Cau, Cader Idris, c.1774. Credit: Tate.

In Britain, the first important artist to paint landscape for its own sake, with little of obvious "human interest," was a Welshman, Richard Wilson (1712/3-1782). Well-educated and highly cultivated, Wilson took his early inspiration for landscape painting from these Mediterranean sources. He was born in Penegoes in Montgomeryshire (the northern part of present-day Powys), and became one of the prominent artists of his time, so much so that he was among the founder members of the Royal Academy in 1748. Despite his success as a portraitist, he was already developing a taste for landscape painting. When he went out to Italy in 1750, he was further influenced in this direction by Claude's work, and by the scenery around Rome which once inspired Claude himself. Peter Lord feels that Wilson was also influenced by Gaspard Dughet (1615-1675), Poussin's pupil and later brother-in-law (109). On returning home, Wilson found his own source of inspiration in the scenery of England and Wales, quickly establishing himself as "a landscape painter in the classical, grand style" (Solkin) and earning a solid reputation for it. He was helped in this by the new status afforded Welsh culture. The Cymmrodorion Society, established in London with a name that means "original inhabitants," reflected and augmented a new wave of interest in this culture, and while Wilson was never a member, he clearly shared its outlook (see Lord 6). The painting of Lyn-y-Cau in North Wales (above right) shows a big development from the self-consciously artistic work he did while in Italy. The artist and his observer here are not in the frame at all. Instead he conveys quite directly his awe at the sunken lake amid the grassy slopes and boulders, seemingly tilted towards us for full effect. Human figures are tiny here, lost in the larger scene. Wilson's patriotism added to the sense of conviction in his work, the sense that here, at home, were subjects to engage the spirit and skill of the finest artists. Sadly, his health and reputation began to fail in the 1770s, perhaps as a result of alcoholism. But he is now acclaimed for having been central to the early history of British landscape-painting, as well as being celebrated in Wales as a pioneer of Welsh painting.

III: Landscapes of the Netherlands

View on the Amstel Looking towards Amsterdam, by Jacob van Ruisdael (1628/1629–1682), c. 1680. Collection: Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, accession no. 74, kindly made available on the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (CC BY-NC-ND).

From Holland and Belgium, however, came another source of inspiration which expressed itself not in the "Grand Manner" of classical art, but in more familiar and picturesque rural scenes. Here, artists were painting landscapes with views across the flat expanses of their countryside, with small points of interest lovingly recorded, often with vast skies overhead. An example here is Jacob van Ruisdael's View on the Amstel Looking towards Amsterdam, shown above, with its many intimate features of Dutch rural life, including farmland, houses, windmills, the waterway itself, and the distant spires of the capital. The sky too is not featureless, but captures and holds for a moment a lively panorama of scudding clouds. If not from the classical past, where did the impulse for such scenes originate? Clark believes that it sprang from "the need of recognisable, unidealised views of their own country, the character of which they had recently fought so hard [during the Anglo- and Franco-Dutch wars of the seventeenth century] to defend" (79). It may also, Clark believes, be a reflection of people's relief that peace had returned, at least for the time being. Such outdoor scenes, like those of domestic life by Johannes Vermeer (1632-1685) and others, also spoke to British painters: "as a native of East Anglia," Clark says, John Constable was bound to have been familiar with paintings like this in local galleries (see p. 175).

IV: Turner, Constable and the Norwich School

Turner's Chichester Canal, c. 1828. Credit: Tate.

By now, there was a further incentive to seek out the beauty of nature: it was under threat, not from war, but from industrialisation and urbanisation. The Romantics were hymning its praises, and lost in wonder at its might. Fortunately, Richard Wilson's unhappy decline did not diminish his long-term influence. His example drew many other artists to the scenery of North Wales at this time. Indeed, J.M.W. Turner admired his work so much that in 1798, on one of his tours of Wales, he made a special pilgrimage to his birthplace at Penegoes. According to Lord, some of Turner's paintings of Welsh landscapes from that period, at the very end of the nineteenth century, "showed unmistakable signs of the influence of Wilson" (157). We can imagine that a painting like Wilson's Lyn-y-Cau, Cader Idris (section II above, right), with its enhanced perspective evoking a sense of awe, would have appealed to Turner. Here again was, if not quite in the restrained "Grand Manner" of the past, at least an unmistakeably elevated vision. Yet the still more visionary quality of Turner's own later landscapes, with his even greater skill than Wilson's in conveying the effects of light, set him apart from the Welsh artist. As Turner's rival John Constable noted after an exhibition in 1836, "he [Turner] seems to paint with tinted steam, so evanescent, and so airy" (qtd. in Leslie 315).

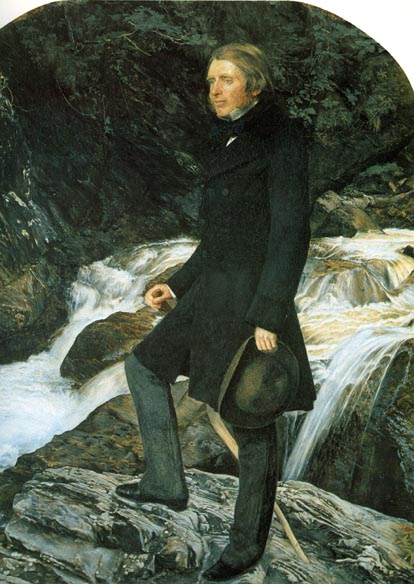

John Everett Millais's portrait of John Ruskin, in a

highly appropriate natural setting, 1853-54.

Turner's most memorable work, in fact, represented a dramatic departure from the classical impetus. It brought him the full support of John Ruskin: "The aim of the great inventive landscape painter," said Ruskin, "must be to give the far higher and deeper truth of mental vision, rather than that of the physical facts, and to reach a representation which . . . shall yet be capable of producing on the faraway beholder's mind precisely the impression which the reality would have produced" (qtd in Landow 32). Like the art that it encouraged, such views might not seem at all revolutionary now. But, at that time, they were. After all, it has taken us centuries to accept that nature is not simply a backdrop to our lives. The science of ecology is a new one, dating only from the later part of the last century. But Ruskin knew already that we experience nature with all aspects of our being, with both intellect and our senses; that we are no more separate from it than any other living organism; and that the "great inventive landscape painter" has the unique ability to make others more conscious of our fundamental and indissoluble connection with it.

Despite the importance of both Wilson and Turner, it is probably true that Constable himself, and the painters of the Norwich School — John Crome (1768-1821), John Sell Cotman (1781-1842), Joseph Stannard (1797-1830) and others — were the artists who really established landscape painting as a genre here. When writing to his close friend John Fisher, Bishop of Salisbury, on 17 November 1824, Constable expressed the challenge it posed and the reward it offered: "I hold the genuine pastoral feeling of landscape to be very rare and difficult of attainment. It is by far the most lovely department of painting as well as of poetry" (qtd. in Leslie 162). Constable is perhaps best loved for his skies. As his sketchbooks and quick oil sketches or preliminary studies show, he was adept at capturing the clouds in motion, and conveying the very texture they appear to have. The influence of Dutch landscape painting of the "Golden Age" is most apparent here. The V & A's exhibition of "Constable: Making of a Master" in 2014 was memorable for its presentation of his studies, which, set side by side with the finished oils, have an extra and even more appealing spontaneity and freshness about them. Here is the weather, in all its unpredictability, with that famous rainbow in the finished painting of Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows affording not only opportunities for symbolic readings, but proof of our characteristically unstable mix of rain and shine.

Left: Constable's studio sketch for Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, c. 1829. Right: John Sell Cotman's Boats off the Coast, Storm Approaching, 1830. Public domain (photo credit, Met Museum, New York).

Cotman's delicate watercolours, on the other hand, whether they are landscapes or seascapes, have a different kind of appeal, one which reels us into the very heart of them. Turner was a great and long-term admirer (see Binyon 64), and it is no surprise to see Laurence Binyon praising his later work unreservedly: "in the sketches of 1839 to 1842 we find Cotman in a new phase. He returns to nature, intent, as he had rarely been before, on seizing the essential spirit of a scene, not preoccupied with weaving the matter of his vision into his own schemes of form and colour, but submitting his mind to the aspect of things, bent on piercing to the heart of them" (68). We experience with him, says Binyon, "The listless wetness of the beaten branches, the drooping sedges, the empty sky, the blowing wind; how keenly is it all brought to the senses, as with the keenness of physical contact..." (96).

V: Victorian landscape and seascape artists

Benjamin Williams Leader's February, Fill Dyke, 1881.

Constable died in 1837, on the very threshold of the Victorian age. Cotman died five years later. Even Cotman can hardly be said to have been a Victorian. Notable among those of their fellow landscape artists who more thoroughly spanned both the Regency and Victorian eras was David Cox (1783-1859), whose finest work in watercolour belongs to the later decades of his life, when he was producing it "with mercurial ease" (Hardie 203). But by now the field was getting crowded. There was soon a whole raft of painters who excelled in landscapes and seascapes. Christopher Wood, for example, suggests that John Linnell (1792-1882) and Benjamin Williams Leader (1821-1923) "may one day be numbered among our greatest landscape painters" (76), the former staying closer to the kind of classicism found in Claude, the later growing gradually towards a more impressionistic approach.

Some of the Victorian landscapists, like Samuel Palmer (1805-1881) and the "Ancients," were still imbued with the glow of Romanticism; others, like Leader, were similarly nostalgic, perhaps with an eye to the market rather than any lofty ideals. Among such artists were the West Country father and son William Widgery (1822-1893) and Frederick John Widgery (1861-1942), the former quite untaught but amazingly prolific, who celebrated the beauty of their rural surroundings and sold their work to locals as well as visitors almost before their paint was dry. These artists held a particular appeal for urbanites, including (rather ironically) the new industrialist art-lovers, who wanted to display their cultural credentials in their new country homes. Many, like John Martin 1789-1855), the epic scale of whose vision was utterly removed from any kind of nostalgia, also contributed to the new British "Golden Age" of illustration. Engravings spread these artists' best work among all classes of society.

February in the Isle of Wight, by John Brett, 1866 An Artist Painting by the Sea, by John William Inchbold, 1887.

So wide-ranging, so various and popular was this body of landscape art that it seems incredible now that earlier artists had not always drawn freely on scenery for their inspiration. In our own times, it is simply taken for granted that, diverging from the more narrowly topographical, the Victorians' approach to the natural world was coloured by the artist's own eye, and evokes a depth of response in the onlooker. "Taking it for granted" helps to explain why the landscape movement of the early nineteenth century has indeed "never received a fraction of the praise which is its just due" (Harrison 5).

But there are other reasons. The greatest early exponents of it, Constable and Turner, whom Lionel Lambourne calls "the twin peaks of English landscape painters" (94), were above categorising. Then, as the century moved on, many important practitioners got more of their identity from the schools or movements with which they were associated. John William Inchbold (1830-1888) and John Brett (1830-1902), for example, are often seen as Pre-Raphaelite associates; John William North (1842-1924) was seen as a member of the Idyllic School; and William McTaggart (1835-1910) and Peter Graham (1838-1921) as Scottish artists. Towards the end of this century and in the early part of the next, another group appeared, attached to Giovanni Costa and his "Etruscan" style, harkening back to some extent to the spirit of Claude and Poussin. Among these were Matthew Ridley Corbet, his wife Edith, and William Blake Richmond.

Matthew Ridley Corbet's Etruscan-style Val d'Arno: Evening, exhibited 1901.

Then too, many landscape artists were equally at home in other genres. Even James Clarke Hook (1819-1907), so well known for his rural scenes and marine "Hookscapes," had considerable success with literary and historical subjects as well. One thing, however, is abundantly clear — that during the nineteenth century both land- and sea-scapes found a prominent and permanent place among our best loved forms of art.

Link to Related Material

Bibliography

Andrews, Malcolm. Landscape and Western Art. Oxford History of Art series. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Binyon, Laurence. John Crome and John Sell Cotman. London: Seeley & Co./New York: Macmillan, 1897. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of Michigan. Web. 3 March 2022.

Clark, Kenneth. Landscape into Art. London: John Murray, 1976.

Hardie, Martin. Water-colour Painting in Britain: The Romantic Period. Ed. Dudley Snelgrove, Jonathan Mayne, and Basil Taylor. London: B. T. Batsford, 1967. II: 190-209.

Harrison, Birge.

Lambourne, Lionel. Victorian Painting. London and New York: Phaidon, 1999.

Landow, George P. Ruskin. London: Routledge Revivals, 2015. Full text (See Chapter I.)

Leslie, Charles Robert. Life and Letters of John Constable. London: Chapman & Hall, 1896. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Getty Research Institute. Web. 1 March 2022.

Lord, Peter. Imaging the Nation: The Visual Culture of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2000.

Newall, Christopher. A Celebration of British and European Painting of the 19th and 20th Centuries. London: Peter Nahum, nd.

Wood, Christopher. Victorian Painters. 2. Historical Survey and Plates (Dictionary of British Art Volume IV). Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors' Club, 1995.

Created 5 March 2022

Last modified 28 August 2022