ary Seacole and Florence Nightingale were contemporaries

noted for their nursing care of soldiers during the Crimean War.

Nightingale is still a well-known historical figure, but Seacole was soon forgotten.

One author asked, 'Why is it then that the sands of history seem to have buried

Mary Seacole in favour of Miss Nightingale and others when her deeds were in

many ways equally noble?' Mrs. Seacole was a Jamaican healer or 'doctress' with

expertise in tending victims of cholera

and yellow fever epidemics. When the Crimean War began, Mrs. Seacole went to

London and volunteered her services as a nurse to the War Office, other military

agencies, and Florence Nightingale's nursing group. She was told by all that

her services were not needed. She went to the Crimea at her own expense and

worked steadfastly to care for the sick and wounded, often going onto the battlefield

to aid the fallen. She became quite well known in the Crimea and back in England.

Her autobiography, The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands,

was published in 1857 and was very popular for a while. Then Mrs. Seacole faded

from public attention for almost 100 years. In the 1970's Mrs. Seacole was rediscovered

and has become a symbol for Black nurses, civil rights groups, and the women's

liberation movement. Almost every article available compares her with Florence

Nightingale and suggests that Mrs. Seacole was pushed aside and soon forgotten

because she was Black. In this paper I will discuss Mary Seacole's life and

works in light of the time period in which she lived, the comparisons made between

Seacole and Nightingale, and the body of literature that has been written about

her.

ary Seacole and Florence Nightingale were contemporaries

noted for their nursing care of soldiers during the Crimean War.

Nightingale is still a well-known historical figure, but Seacole was soon forgotten.

One author asked, 'Why is it then that the sands of history seem to have buried

Mary Seacole in favour of Miss Nightingale and others when her deeds were in

many ways equally noble?' Mrs. Seacole was a Jamaican healer or 'doctress' with

expertise in tending victims of cholera

and yellow fever epidemics. When the Crimean War began, Mrs. Seacole went to

London and volunteered her services as a nurse to the War Office, other military

agencies, and Florence Nightingale's nursing group. She was told by all that

her services were not needed. She went to the Crimea at her own expense and

worked steadfastly to care for the sick and wounded, often going onto the battlefield

to aid the fallen. She became quite well known in the Crimea and back in England.

Her autobiography, The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands,

was published in 1857 and was very popular for a while. Then Mrs. Seacole faded

from public attention for almost 100 years. In the 1970's Mrs. Seacole was rediscovered

and has become a symbol for Black nurses, civil rights groups, and the women's

liberation movement. Almost every article available compares her with Florence

Nightingale and suggests that Mrs. Seacole was pushed aside and soon forgotten

because she was Black. In this paper I will discuss Mary Seacole's life and

works in light of the time period in which she lived, the comparisons made between

Seacole and Nightingale, and the body of literature that has been written about

her.

Twenty-five years ago, it would have been difficult to find many people who recognized the name of Mary Seacole except for a few nurses in her home country of Kingston, Jamaica. However, there was a time when she was quite famous in England as well as in the Caribbean. Mary Seacole is rather an elusive figure because she never held any 'official' appointments nor did she leave behind a large body of written works. Mary published her very popular autobiography in 1857. In addition, there were a few articles about her actions in the Crimean War published in the London Times, Punch, and the Illustrated London News. On her death in 1881, the Times and the Manchester Guardian paid tribute to a woman whose personal courage and contribution to the Crimean campaign had won her wide admiration (Alexander, 1981). In time, the people who knew of her work died and the fame she earned for her work with the sick and wounded in the Crimea as well as all she did in the Caribbean to help with victims of yellow fever, cholera, dysentery, and other tropical diseases, faded from memory. There were, of course, a few people in Jamaica who remembered because Mary Seacole was one of their most famous citizens. I did an extensive literature search to find out more about the woman who is now being called another Florence Nightingale, the Black Florence Nightingale, and the first nurse practitioner. I will start with some illustrations from Mary Seacole's autobiography as background material and then discuss some of the articles that have been written about her since she was 'rediscovered.' All references to Mrs. Seacole's autobiography will refer to the Alexander & Dewjee reprint edition.

Almost everything known about Mary Seacole is to be found in her autobiography entitled Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands which was originally published in London in 1857 and reprinted in 1984. She reveals very little personal information about herself. Her childhood and family life is summarized in six pages. She was born Mary Ann Grant in Kingston, Jamaica in 1805. Her mother was a free Black woman and her father was a Scottish soldier stationed in Kingston. Slaves were not freed in the British West Indies until 1834 so Mary occupied a middle ground; not a slave but still subject to the prejudices against Blacks. Mary was a mulatto or Creole. On the first page of her book, she described herself: 'I am a Creole, and have good Scotch blood coursing in my veins' (Alexander, 1984). Mary's mother was a well-known herbalist or 'doctress' in Kingston. She ran a boarding house for invalid British soldiers and their families. Mary seems to have had frequent contact with military doctors and keenly observed what they did to treat their patients. By the time she was twelve, she was helping her mother take care of patients. She claimed she inherited her energy and ambition from her Scottish father and her medical skills from her mother. She married a Mr. Seacole in 1836 but he was a sickly man and soon died. In her book, Seacole only refers to him as Mr. Seacole but various sources give his name as Edwin Horatio Seacole. Two main points are emphasized throughout her book — she loved to travel and she had a strong interest in medicine and serving the sick. While she was still young, she made two trips to England and lived there for a total of three years.

After she became a widow, Mary established her own boarding house and began to care for her own patients. She gained a reputation as a skilled nurse and doctress. In 1850 cholera swept the island of Jamaica and more than 31,000 people died. Mary worked with doctors as a fledgling nurse, gaining first hand knowledge of the disease and developed a medicine that produced remarkable results (King, 1974). Since there were no formal nursing education programs yet, she was as well qualified as anyone to call herself a nurse. She observed the illness and studied what worked and what didn't. Ever restless, Mary traveled to Panama to visit her brother and opened a boarding house in Cruces. Panama was in a state of upheaval at the time and sanitary conditions were extremely bad. That, combined with the hot, humid weather, made Panama a breeding ground for all types of tropical diseases. Soon after Seacole's arrival, cholera broke out in Cruces. There was no doctor but the residents were reluctant to accept her help at first because she was black and she was a woman. However, they were soon forced to seek her aid. She worked night and day until the crisis was over and was credited with saving many lives. She said the disease was contagious but that wasn't the usual belief for quite awhile. She also felt that cleanliness, fresh air, and good food were important even though those ideas weren't commonly accepted. She was very observant and wanted to know the mechanisms involved in cholera. Finally, she did her one and only autopsy on a child who had died of cholera because she wanted to see what was going on inside the body of victims. She received much acclaim and praise for her work in Cruces. Americans living in Panama called her an angel of mercy, but some of the Americans provoked her to wrath because of their racist remarks and bad attitudes about Blacks. While in Cruces, she made a statement that illustrates the driving force in her life: 'And wherever the need arises — on whatever distant shore — - I ask no higher or greater privilege than to minister to it' (Alexander, 1984, p. 78). She moved on to Cuba and was so effective in caring for their cholera victims that she became known as 'the yellow woman from Jamaica with the cholera medicine.' Mrs. Seacole moved back to Kingston and was there in 1853 when a severe yellow fever epidemic struck Jamaica. Once again she worked tirelessly in treating the sick.

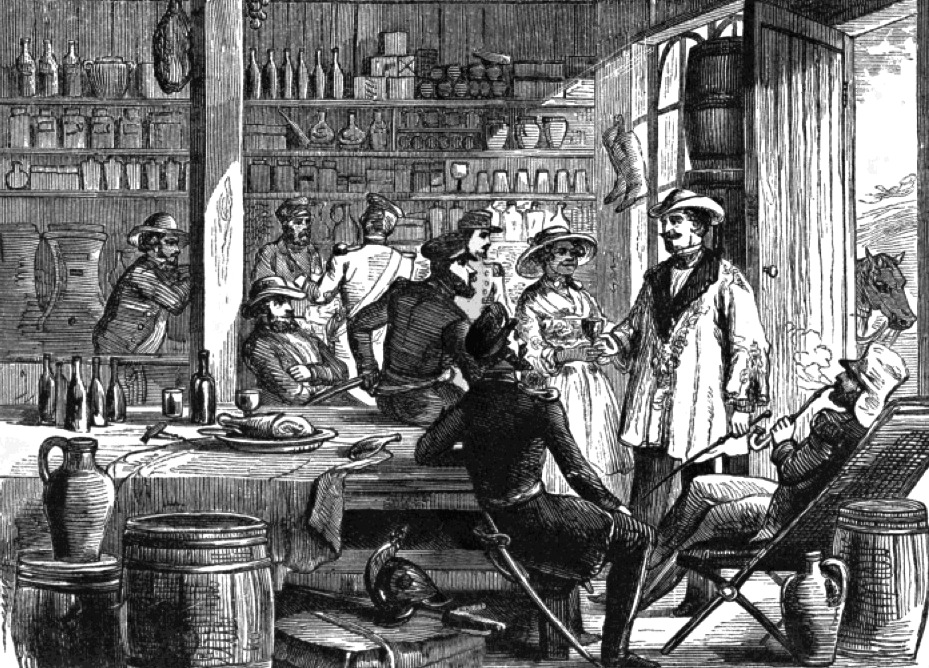

Mrs Seacole's Hotel in the Crimea. Source: Fronispiece, Seacole.

When war broke out in the Crimea, some of the units from Jamaica were sent there to fight. Reporters such as Times correspondent, William H. Russell, sent back regular reports on the horrible conditions for the sick and wounded. Of the 20,000 British soldiers who lost their lives in the war, 3000 died in battle and the remaining 17,000 from diseases. Florence Nightingale was recruited to organize and train nurses to work in the military hospitals of the Crimea. When news of the situation in the Crimea reached Mary Seacole, she was convinced that her experience with tropical diseases was vital to Britain's war efforts (Alexander, 1981). Mary was very attached to her 'boys' from Jamaica and wanted to join the regiments she knew from Kingston in Sebastopol. Armed with glowing letters of recommendation from military doctors in Jamaica, Seacole arrived in London in the autumn of 1854. First, she applied to the War Office for the post of hospital nurse because in her own words she said, 'knowing that I was well fitted for the work, and would be the right woman in the right place' (Alexander, 1984, p. 123). The War Office ignored her offer. Then she applied at various military offices and with Florence Nightingale's organization. In spite of a great shortage of suitable women to go to the Crimea as nurses, she was turned down by all. Finally, bitterly disappointed that no one seemed to want the help she was freely offering, Mary wrote in her autobiography:

Doubts and suspicion rose in my heart for the first and last time, thank Heaven. Was it possible that American prejudices against colour had some root here? Did these ladies shrink from accepting my aid because my blood flowed beneath a somewhat duskier skin than theirs (Alexander, 1984, p. 126)?

Mary shed a few tears of grief that all the officials doubted her ability, but then her determination came to the fore and she decided she would go to the Crimea at her own expense. She said, 'if the authorities had allowed me, I would willingly have given them my services as a nurse; but as they declined them, should I not open an hotel for invalids in the Crimea in my own way?' (Alexander, 1984, p. 126). One of her guiding principles was that bureaucracy should not deter the cause of service (Marshall-Burnett, 1981). In partnership with Thomas Day, a distant connection of her late husband, she acquired a stock of food and medicine and left for Turkey as a sutler. She set up a store and boarding house about two miles from Balaclava which she called The British Hotel. Her purpose was to establish an eating establishment and comfortable quarters for sick and convalescent officers. The lower floor was a restaurant and bar and the upper floor was similar to a hospital. Throughout her career, Mrs. Seacole was an astute businesswoman. Her boarding houses provided for her personal expenses and financed her medical work. She was very generous in serving others, but she also expected to be paid for her services. She worked in her boarding house by day and then volunteered with Florence Nightingale in the evening. She began a medical practice working with the 'ranks' or enlisted men who did not want to go to the hospitals for any reason. She soon held the position in camp as doctress, nurse, and 'mother.' In her book she uses many letters she received in appreciation for her care. Her fame increased even more when she was seen tending the wounded on the battlefields even as the battle was still taking place. She became a familiar sight in her colorful garb such as her 'yellow dress and blue bonnet with red ribbons and her famous medical bag' (Alexander, 1981, p. 45). She regularly loaded her bags of provisions on one mule and her black bag of 'medical equipment', lint, bandages, needle and thread on a second mule, and made her way to the scene of battle. When Sebastopol fell on September 8, 1855, Mrs. Seacole got a pass that allowed her to be the first woman to enter Sebastopol so she could pass out refreshments and tend to the injured. The soldiers began to call her the 'black Nightingale.' Even though she was praised highly by the soldiers, she was never given any official recognition or reward by the military. When the war ended abruptly in 1856, Mrs. Seacole was left with a lot of expensive supplies that she could not sell at a fair price so she suffered a great financial loss. After she returned to England she had to declare bankruptcy. High-ranking officers and others who knew of her work in the Crimea started a fund for her and staged a four-day benefit to help her financially. Despite very large crowds at the benefit, Seacole received very little money. Due to poor planning and the financial problems of the Royal Surrey Gardens, the profit was about £233 after expenses were paid. Though her heroism in the Crimea went unheralded by the government, Mary Seacole had won the admiration, respect, and love of many of the English people. The British weekly, Punch, wrote a glowing tribute to her in a poem entitled 'A Stir for Seacole' which was published December 6, 1856 and Times correspondent, William H. Russell mentioned her in some of his news reports and later wrote the introductory preface to her autobiography. Among other flattering comments, he said:

I have witnessed her devotion and her courage; I have already borne testimony to her services to all who needed them. She is the first who has redeemed the name of 'sutler' from the suspicion of worthlessness, mercenary baseness, and plunder; and I trust that England will not forget one who nursed her sick, who sought out her wounded to aid and succour them and who performed the last offices for some of her illustrious dead (Alexander, 1857/1984, Preface).

Mary's book was very well received and profitable. In 1867 another fund was established which had the backing of Queen Victoria. The goal of her supporters was 'to place her beyond the reach of want' (Alexander, 1984, p. 34). Long after the war ended, the government awarded her the Crimea Medal for services rendered the sick and injured (Carnegie, 1984). The Times reported that she received four medals but didn't specify what they were. An obituary article in the Daily Gleaner of Jamaica dated June 9, 1881, stated that Mrs. Seacole received 'English, French, Russian and Turkish decorations.' The latter years of Mrs. Seacole's life were divided between Jamaica and England. Mary died in Paddington, London on May 14, 1881. Her estate was valued at something over £2600. The Times and Manchester Guardian published obituaries in recognition of her services even though she had been out of the public eye for 25 years. After that, Mary Seacole faded from memory.

During my literature review on Mary Seacole, I found a few references about her in Jamaica in 1905, 1911, 1932 and 1934. In a 1951 radio broadcast, Adolphe Roberts said, 'posterity will remember a Jamaican, who although she may not be counted among the world's 'greats', certainly had one of the kindest hearts that ever beat in a human breast' (Roberts, 1951).

The first serious attempt to restore her place in history was in 1954, the centenary of the Crimean War. In that year, the Jamaican General Trained Nurses' Association (now the Jamaican Nurses' Association) decided to name their Kingston headquarters the Mary Seacole House when it was built. Later a residence hall at the University of the West Indies was named for her, and then a ward in the Kingston Public Hospital. No recognition of any significance occurred in Britain until 1973.

On November 20, 1973 there was a special ceremony of reconsecration at Mary Seacole's grave. Miss Elsie Gordon, former editor of the Nursing Mirror found a slip of paper in an old copy of Mrs. Seacole's autobiography that she had purchased in a London book shop. This piece of paper helped Gordon locate Mary Seacole's grave in St. Mary's Roman Catholic Cemetery in Kensal Green. Prior to this, no one knew where she was buried (Gordon, 1975). The ceremony was due to the combined efforts of the British Commonwealth Nurses' War Memorial Fund and the Lignum Vitae Club, a Jamaican women's group based in London, and the support of the Jamaican Nurses' Association (U.K.). Mrs. Seacole's crumbling headstone was restored. This ceremony received coverage in newspapers and several nursing journals. In 1980, a touring exhibition called 'Roots in Britain' occasioned many requests for further information on Mary Seacole. Due to this revived interest, a memorial service was held on May 14, 1981 to mark the centenary of her death. This commemorative service has now become an annual event. The response was so strong that a decision was made to reprint Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands in 1984. The editors of the reprint, Ziggi Alexander and Audrey Dewjee added several pages of research to their introduction which greatly expanded the information available on Mrs. Seacole and her autobiography. In a review of the book, Clive Davis remarked that 'A cottage industry is beginning to develop around the exploits of 'Mother Seacole', a Jamaican Creole who became a Victorian celebrity for her work as a nurse in the Crimean War and then sank into obscurity for the next hundred years or so' (Davis, 1984).

As her story became better known, Mrs. Seacole was turned into a symbol or rallying point for minority nurses, feminists, and nurses who felt the current system of nursing was too restrictive. Black nurses began to complain of the racism in the National Health Service and used Mary Seacole's words to express their feelings of anger and rejection: 'Did they shrink from accepting my aid because it flowed from a somewhat duskier skin than theirs' (Alibhai, 1988). The question of why Florence Nightingale became so famous that she is still remembered today while Mrs. Seacole received little recognition began to appear with more regularity. One asked, 'Why is it then that the sands of history seem to have buried Mary Seacole in favour of Miss Nightingale and others when her deeds were in many ways equally noble' (Bassett, 1992). Nurses who were interested in what is now called advanced practice nursing pointed out that Seacole's practice and conduct was of great significance to the genesis and history of nursing. It is true that Mary Seacole did nurse but her practice was far broader — diagnosis, prescription, preparation of herbals and pharmaceutical medicine, a little minor surgery, and doing a postmortem on a cholera victim to learn more about the effects of cholera. Hopefully she will eventually have her own place in history instead of being 'a black Nightingale' (Pollitt, 1992). Seacole has also been called a nurse practitioner, independent practitioner, or advanced practice nurse because she performed a number of nursing and medical activities without direct supervision from a doctor. In fact, many doctors felt threatened by her ideas on cleanliness, good ventilation, nourishing food, and the separation of patients with contagious diseases. Furthermore, she financed her own practice due to her shrewd business skills in owning and managing her boarding houses and in being a sutler during the Crimean War.

A recurring theme in almost every article about Mary Seacole is the comparison of Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole. Florence Nightingale still has great name recognition all over the world while Mary Seacole was known for perhaps 30 years and then forgotten. They both served in the Crimean War and both did everything within their power to relieve the suffering of the sick and wounded soldiers. Florence Nightingale was white and had the backing and support of the British government. Mary Seacole was a middle aged Creole from Jamaica — a British colony. She volunteered her services as a nurse and had the credentials to show that she was very experienced in working with diseases such as cholera, yellow fever and dysentery. She was told by all that her services weren't needed even though that was blatantly untrue. Therefore, she went at her own expense. As many of the articles about her claim, racism in the Victorian society of her day was undoubtedly the major reason for her rejection. However, some of the articles seem to infer that, somehow, it was all Florence Nightingale's fault. One article stated, 'she had to compete with Florence Nightingale whose work was well established. Florence Nightingale was in a position to achieve what she wanted, how she wanted, and she was also a woman who wished to do it alone … Florence Nightingale saw Mary as an independent, strong willed rival' (Iveson-Iveson, 1983, p. 45). One wonders why there was a need for competition since there was enough work to keep any number of nurses busy. One of Florence Nightingale's major goals was to make nursing a respectable profession. Nurses often had a very bad reputation for being sloppy, drunken women who weren't much better than prostitutes. Image was just as important then as it is now. Along came Mrs. Seacole, a colonial from Jamaica. By her own admission, Mary was rather flamboyant — a very colorful and picturesque character who liked to dress in conspicuous colors like red and yellow, and wear hats or bonnets decorated with a lot of red ribbons. She obviously didn't fit the image. Mrs. Seacole was ahead of her time in more ways than one!

Another dubious charge is that, 'In many ways she stands head and shoulders above Florence Nightingale, for whereas Florence performed only an administrative role away from the front line, Mrs. Seacole was in the thick of things and did not hesitate to go to the battlefield itself in her desire to alleviate suffering and to comfort the dying' (Iveson-Iveson, 1984, p. 36).

The manner of their service was drastically different. Even before she went to the Crimea, Nightingale knew that surmounting the bureaucratic problems of the army's medical services and establishing a female nursing group which authorities and medical men alike could respect was going to be more important than any individual patient care she might do. Nightingale gained her reputation by the organization of nursing services during the Crimean War. After the war she worked tirelessly to improve public health and raise the status of nursing. The result of the introduction of women nurses into the British Army was no small matter in the history of nursing and was a testimony to her tremendous public support in forcing the antagonistic military hierarchy to accept a female with authority into their ranks. She also experienced prejudice and resentment from doctors and the military establishment. Nightingale is being criticized for not doing more, for not being more progressive, etc. but she took on the establishment years before women could even vote. Mrs. Seacole's strength seemed to be more in hands-on activities such as direct patient care. She was an entrepreneur who was able to use her skills as a merchant to finance her medical and nursing practice. It is probably true that Mrs. Seacole had more practical experience, especially with tropical diseases. However, both administrative and hands-on care are necessary for the effective delivery of health care. Both women made a great contribution to the history of nursing in their own way and, hopefully, there is room for both of them.

Mrs. Seacole's autobiography has generated several articles which analyze it as a travel book. It was unique for women to travel freely and alone in Victorian times. Some have even questioned that she really wrote the book herself. The assumption seems to be that a Black woman from the colonies wouldn't have been able to write such a book. However, many of the freeborn Blacks seem to have been quite well off and educated. Seacole's book is written in a lively, racy manner that is easy to read. Her caustic wit and optimistic attitude are very engaging. It is ironic that most of the articles about Mrs. Seacole claim she was overlooked because she was a victim of Victorian racism, but in her book, she frequently makes derogatory remarks about Blacks, Creoles, Catholics, and the Irish. Inevitably, she points out that thankfully, she doesn't have whatever bad habits these other people have. She was also a name dropper but reviewers seem to feel she did that mostly to promote her book by giving her story validity. She didn't say much about slavery in her own country or Britain's role in it, but she did sharply criticize Americans and their treatment of Blacks. She stressed her Scottish heritage and referred to herself as a yellow woman or a person with yellow skin rather than being black. In her book she presents herself as a rational observer of people and events happening around her. She was obviously writing for a white, British audience since they would be the ones to buy her book, the purpose of which was to rescue her from her financial problems. Mrs. Seacole's autobiography may seem like an interesting travel adventure on the first read but when one remembers the slavery issue and her rather ambiguous role as a free Black woman in Victorian society, it is obvious that she was walking a rather fine line in writing the book at all.

In answer to the question of why Florence Nightingale was revered in her time and still remembered today while Mary Seacole was soon forgotten, racism and Victorian prejudices were probably the primary cause. One could also ask, what is the nature of greatness?

To be recorded by official institutions, an individual or event must at some stage be deemed to be of particular value to society. The notion of 'greatness' is a highly subjective one, governed by considerations of race, class and gender, and by a person's or event's place within our affections (Okokon, 1998).

History is written by those in power at the time. Once Mrs. Seacole's supporters and admirers died, there was no one to keep her name alive. On the other hand, Florence Nightingale had a school named after her and left behind a large body of literature including her Notes on Nursing which was almost a bible for nursing well into the 1900s. These things helped to perpetuate her memory. It was a strange coincidence that these two women who were motivated by the same need to serve were contemporaries. Unfortunately for Mary Seacole, Florence Nightingale fitted the Victorian idea of a heroine better than she did. One could ask whether it is more important to be a doer or a thinker, or in this case, an administrator or a bedside nurse. Mary Grant Seacole rose about the barriers of racial prejudice and demonstrated determinism, compassion, and caring and is a fitting role model for both blacks and non-blacks. There is much to admire in both of these women who had different roles in nursing but the same goal. Although forgotten for many years, Mrs. Seacole has been rediscovered.

References

Alexander, Z. & Dewjee, A. (Eds.). Wonderful adventures of Mrs. Seacole in many lands. Bristol, England: Falling Wall Press, 1984.

Alibhai, Y. 'Black Nightingales'. New Statesman and Society, 1, 26-27. 1988

Bassett, C. 'Mary Seacole: The forgotten founder'. Nursing Standard, 6, 44-45. 1992

Carnegie, M. E. 'Black nurses at the front'. American Journal of Nursing, 84, 1250-1252. 1984

Davis, C. 'Mary Seacole'. [Review of the book Wonderful adventures of Mrs. Seacole in many lands]. New Statesman, 107, 39. 1984

Gordon, J. E. 'Mary Seacole — A forgotten nurse heroine of the Crimea'. Midwife, Health Visitor & Community Nurse, 11, 47-50. 1975.

Iveson-Iveson, J. 'The forgotten heroine'. Nursing Mirror, 157, 44-47. 1983

Iveson-Iveson, J. 'A pin to see a peep show'. Nursing Mirror, 158, 36. 1984

King, A. 'Mary Seacole, Part I: A matter of life …' Essence, 4, 32. 1974

Okokon, S. Black Londoners, 1880 — 1990. Phoenix Mill, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing, 1998.

Pollitt, N. 'Forgotten heroine'. Times Educational Supplement, n. 3965, 33. 1992

Roberts, A. Mary Seacole. Radio Jamaica Broadcast for U. C. W. I. Kingston. Aug. 2 1951.

Seacole, Mary. The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands. London: James Blackwood, 1857 (available offsite on Project Gutenberg, here).

Last modified 30 April 2002