s noted in the section on Houghton’s style, the artist was adept at shifting between idioms, and was able to shift between escapism and realism. In this sense his art is clearly linked to the Pre-Raphaelites, who modelled changes in register and could just as easily represent the contemporary here and now as an imagined (usually medieval) past.

Houghton services a notion of medievalism in his designs for Robert Buchanan’s Ballad Stories of the Affections [1866]. These designs are Pre-Raphaelite in tone, especially in their fascination with quaint costumes and décor. In the two illustrations for ‘Signelil the Serving Maid’, the artist focuses on the patterns in the windows and the elaborate dresses; most striking is the second illustration, which shows a fantastical bed embellished with two birds’ heads, perhaps geese in flight, projecting into the viewer’s space. This is Houghton’s version of the fantastic redundancy that features in the book designs of D.G. Rossetti, and especially in images such as Rosamund by Frederick Sandys (1861). Such imagining of a medieval past that never existed provides a secure space, a domain of contemplative withdrawal from the realities of mid-Victorian life, and Houghton participates in the discourse of evasion that features throughout the art and literature of the period. He also provides an escape in the form of his many images of the Orient, presenting an alternative to the original reader’s world in the form of a dream-imagery which seems entirely tangible, as if observed from reality.

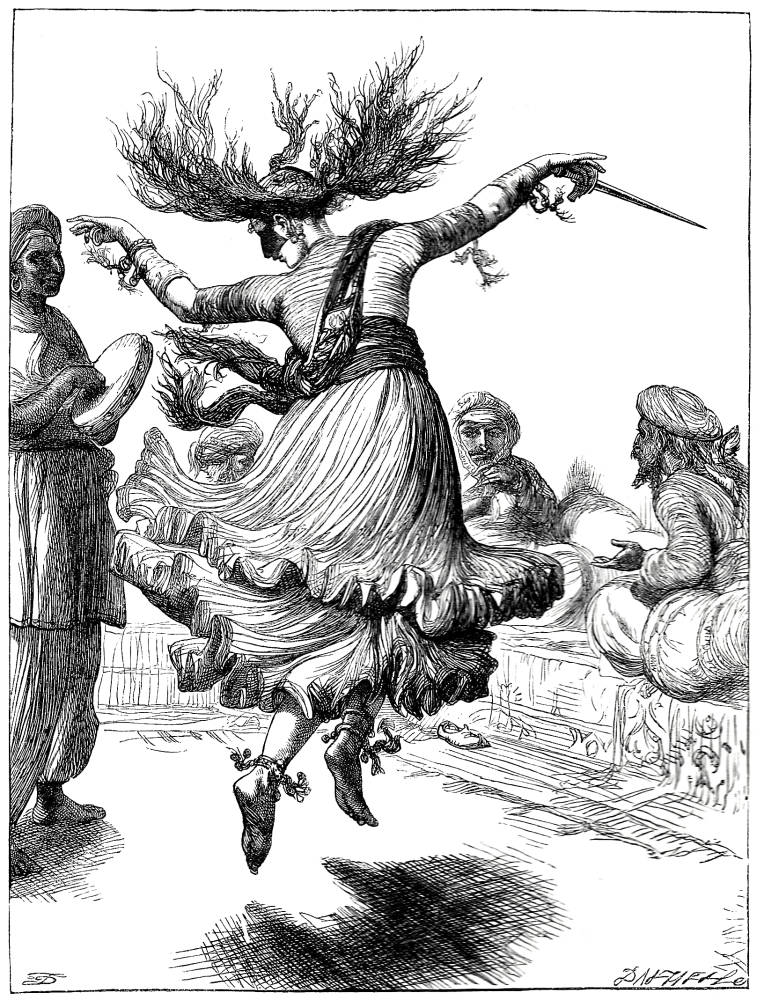

Houghton certainly based his costumes and accessories on real items, although his representations of The Arabian Nights and parallel subjects are far from exact in the ethnographical sense of the term. On the contrary, he copied from ‘collections of curios [and] costumes’ (Dalziels, p.222) that were brought back from India by his father and brothers; unrelated to the Orient, these objects become in Houghton’s hand the magic emblems of cultural Otherness, rather than the signs of a particular place or time. Houghton is probably at his best, on the other hand, when he abandons any attempt at representing his Arab subjects realistically, and presents pure fantasy. This focus is exemplified by two fantastic illustrations, Morgiana dancing before Cogia Houssain, and The Journey of Prince Firouz Schah. In both of these the characters are shown in dynamic poses, rising into the air as if defying the earth-bound limitations of the factual.

Left to right: (a) Signelil. (b) The Journey of Prince Firouz. (c) Morgiana Dancing [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Yet Houghton was as practical as he was imaginative, producing images which give a distinct sense of mid-Victorian society. He provides a detailed portraiture of the bourgoisie, not only in his satirical Home Thoughts and Home Scenes, but also in his sharp characterization of domestic life in A Round of Days and again in Golden Thoughts from Golden Fountains, where the Elizabethan home acts as a proxy for its Victorian equivalent. And he is equally proficient in his treatment of the working classes; as T. Earle Welby remarks, his drawings have an ‘honesty’ (p.78) combined with ‘an unparaded observation of things commonly missed’ (p.79). His Idyllic images of rural life recall the art of George Pinwell and J.W. North, showing the travails of country-life in an unsentimental and dispassionate way which is nevertheless a respectful valuing of the humble and their privations. Reaping, Binding, Gleaning and Carting provide a distinct representation of the hard graft of working in the fields, and this directness is echoed in many other illustrations. He takes this interest much further in his journalistic designs for The Graphic.

Night Charges on their Way to the Station

Images such as Night Charges on their Way to the Station are a dispassionate reading of the situation, and the same cool observation is applied to his work for ‘Graphic America’. Houghton provides a series of observational pieces in which the Shakers are reported, along with everyday scenes that are seen afresh, such as the snow-plough operating in the streets of Boston. Drawings of Native Americans complete the effect, seeming both over-reported and seen as if for the first time. In a curious way, these images were almost as quaint to British eyes as images of the Orient. Like Dickens’s American Notes (1842), Houghton’s designs stress difference rather than similarity, and his ability to find unflattering comparisons between Britain and America, with Britain always being favoured, did nothing for his reputation among American readers.

A poet of the familiar and unfamiliar, who charts the fireside as if it were in a dream or nightmare and re-defines the urban spaces of Britain and America in terms that are eerie and disturbing, Houghton invests his scenes with a sense of novelty and strangeness. Capable of an intense lyrical beauty that bears comparison with the illustrations of Millais, Houghton can take the viewer into new territories of feeling: at once playful and reassuring, his art can be disturbing too. An enigmatic contributor to the traditions of The Sixties, his work is always challenging.

Related Material

- Arthur Boyd Houghton as a stylist: from the Orient to images of the Victorian poor

- Houghton and the representation of children

Last modified 19 August 2013