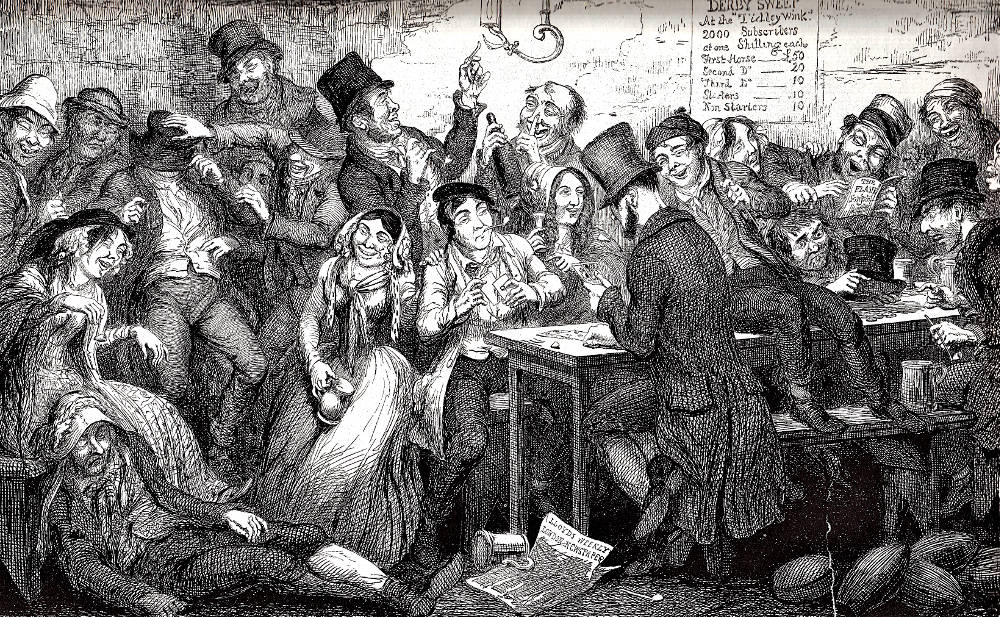

Between the Fine Flaring Gin Palace and the Low Dirty Beer Shop, the Boy Thief Squanders and Gambles Away His Ill-Gotten Gains. — George Cruikshank. 1848. Second illustration in The Drunkard's Children. Folio page: 36 x 46 cm (14.5 inches high by 24 inches wide), framed. Richard A. Vogler points out that Cruikshank reproduced his large-scale drawings by glyphography, "enabling the publisher [David Bogue, London] to sell the entire series for one shilling" (p. 159). "This suite appeared in similar size and editions to that of The Bottle, but it was never reissued in smaller format" (p. 161), except that throughout this sequel the majority of the scenes are not individually signed. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Commentary

Cruikshank now draws the viewer's attention to the noise level of the room and the rough music of a bawdy song which a character at the right end of the table is singing from The Flash Songster. In this crowded barroom scene Cruikshank makes several highly specific contemporary allusions to the low life of the metropolis, including the proletarian weekly newspaper Lloyd's. In the next frame, the figures are animated by orchestral music, although Cruikshank does not depict an actual suite of musicians playing polka music.

Having recently renounced strong spiritous liquors himself and taken the pledge, teetotaller Cruikshank takes viewers from the crowded but tasteful gin palace of Plate I to a far more congested and far less civilized beer shop. Here, the young and still relatively uncorrupted brother and sister consort with the dregs of society in a betting parlour. Since only four of the twenty-one patrons in the frame are females, Cruikshank implies that the low shop's various forms of vice have a distinctly masculine appeal. Cruikshank enables viewers to identify the brother and sister readily by placing their undistorted faces in the centre of the boozing, gambling customers, and by dressing them exactly as in Plate I. The context includes wagering on the "Monster Derby Sweep" (posted on the wall). The shop's sordid customers behave and converse in a coarser manner than that of the people standing just outside the beer-shop in Cruikshank's Oliver Twist illustration from eleven years earlier, Oliver claimed by his affectionate friends (September 1837). These misshapen, inebriated visages in the 1848 beer-shop make Bill Sikes's surly mug seem less boorish. In the centre of the scene of drunken debauchery, the siblings are playing cards with a bearded youth who has presumably been reading the journal of the working classes, Lloyd's Weekly London Newspaper.

The presence of this weekly newspaper at the gambler's feet suggests that the picture is set on a Saturday night, shortly before Edward Lloyd (1815-90) dropped "London" from the paper's bannerhead in 1848 (probably reflecting the growing availability of rail transport for distribution). The radical publisher originally intended Lloyd's, a three-penny paper published on Saturdays for Sunday morning reading by the working class, to be competitive with The Illustrated London News; after seven costly numbers, it became one of two such unillustrated "weeklies" which targeted as readers those who had no vote — the urban poor who owned no property. The News of the World 1843 and the Chartist-oriented Reynolds News in 1850 joined it as "Saturday only" papers. Even before Douglas Jerrold became its editor in 1852, the eight-page Lloyd's had proven popular with working-class readers, achieving a circulation of 90,000, largely in London.

Pointing out that the sister (beside the son) has already become a prostitute, Vogler notes that, in this second frame, the boy is smoking, drinking, gambling, and keeping extremely bad company. Sitting between a pair of prostitutes as if he were Jack Sheppard, the son plays cards with one of the few sober people in the sordid establishment, a serious gamester who has set aside both his pipe and pewter mug in order to focus on the game. In the left-hand register, a pair of fallen women carouse, perhaps on the lookout for clients, as a pickpocket plies his trade on the inebriated customer while a friend (or the thief's confederate) pushes the mark's hat own over his face. The ruffians' faces here resemble that of the boorish Bill Sikes (that is, Cruikshank's Irish tough who had earlier served as Cruikshank's model for Sikes, as Vogler notes, p. 161) in Dickens's Oliver Twist. These criminals also resemble the destructive, drunken hooligans in Cruikshank's illustrations for William Hamilton Maxwell's History of the Irish Rebellion in 1798 — for example, those vandals in Rebels destroying a house and furniture.

In his 1979 commentary, Vogler notes another commonality between this and an earlier illustration: "A man in the center, gin bottle in hand, holds his finger to his nose (for other depictions of this motif, see illustrations 80 [The Three Thimbles], 96 [A Chapter of Noses], and 153 [The Jew and Morris Bolter begin to understand each other])" (p. 161). With its boozing, card-playing, and general disorder, this scene recalls the work of William Hogarth rather than that of other Victorian illustrators such as Hablot Knight Browne. And, like Hogarth, Cruikshank here does not attempt to mediate his acute vision of low-life animal spirits with comedy, pathos, or sentimentality. His approach here calls to mind that of Hogarth in A Midnight Modern Conversation (1733), in which excessive tobacco and alcohol consumption has rendered comatose, falling-down-drunk, or narcotized ten middle-aged males, a group about which nothing is even vaguely cerebral. As a detail that supports the downward trajectory of the second series, Cruikshank provides a crude, unscreened lighting fixture quite different from the elegant glass gas-jet-covers in the first plate. The drunk in the woman's bonnet man who has passed out (lower left) epitomizes the transgressive nature of the scene; with so many open mouths and so many vacuous expressions, one can easily imagine the cacaphonous din of so much pointless laughter, punctuated with snatches of song from The Flash Songster (right), a tiny booklet containing a collection of slangy, erotic lyrics in the cant of the lower classes — flash (racy street) language.

The Flash Songster: Musical Erotica

With titles such as The Luscious Songster and The Libertine's Songster such short-run publications in flash language circulated freely in proletarian districts of London. A prime example of the period, The Funny Songster, bears the subtitle an extensive collection of flash, amatory, and comical songs (London, Metford [i. e., John Duncombe, c. 1833]. pp. 48).

[Another edition.] The swell's night guide; or, A peep through the great metropolis, under the dominion of Nox: displaying the various attractive places of amusement by night: the saloons; the Paphian beauties; the chaffing cribs; the introducing houses; the singing and lushing cribs; the comical clubs; fancy ladies and their penchants, &c, &c.: revised, and carefully corrected, by the Lord Chief Baron [i. e., Renton Nicholson], the arbiter elegantiarum of fashion and folly: with numerous spicy engravings. [London] 1846. pp. [i] 136. pl. [8]

The closing stanza of "The Feather-Bed Dance" (reprinted in Bawdy Songbooks of the Romantic Period, 2011) gives the modern reader some sense of the ribald nature of such underground publications, as well as of popular dance-steps of the period:

Then away with your waltz, gallopade and quadrille,

Your wild Irish fling, and your Highland three reel.

The joys that alone boy and maiden entrance,

Are the beautiful moves of the feather-bed dance!

[A favourite Flash Song, sung at the Cider Cellar]

Sometimes topical allusions crop up in these limited circulation chapbooks; for example, The Rambler's Flash Songster, nothing but out and outers, adapted for gentlemen only, etc. (London: [West, 1838?]) responds to the burning of the Parliament buildings with the comic song "Oh, What a Flare Up!" (c. 1838), pp. 32-4. As Derek B. Scott notes, "The songbooks of the 1830-40s were printed in tiny numbers, and small format so they could be hidden in a pocket, passed round or thrown away." The present example, smaller than a modern paperback, fits this description precisely. Through the topical allusion Cruikshank extends the visual medium, incorporating an auditory dimension rarely found in nineteenth-century illustrations. Here, for example, the rough music of flash songbook, from which the three rowdies with bad teeth are singing (right) complements the tavern's noise.

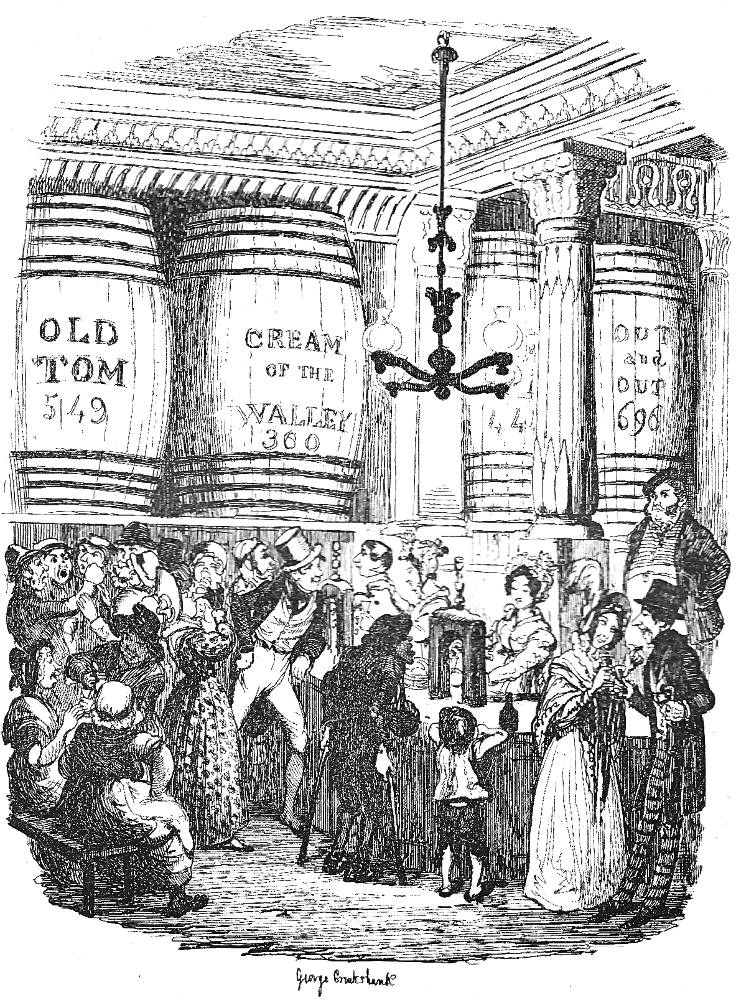

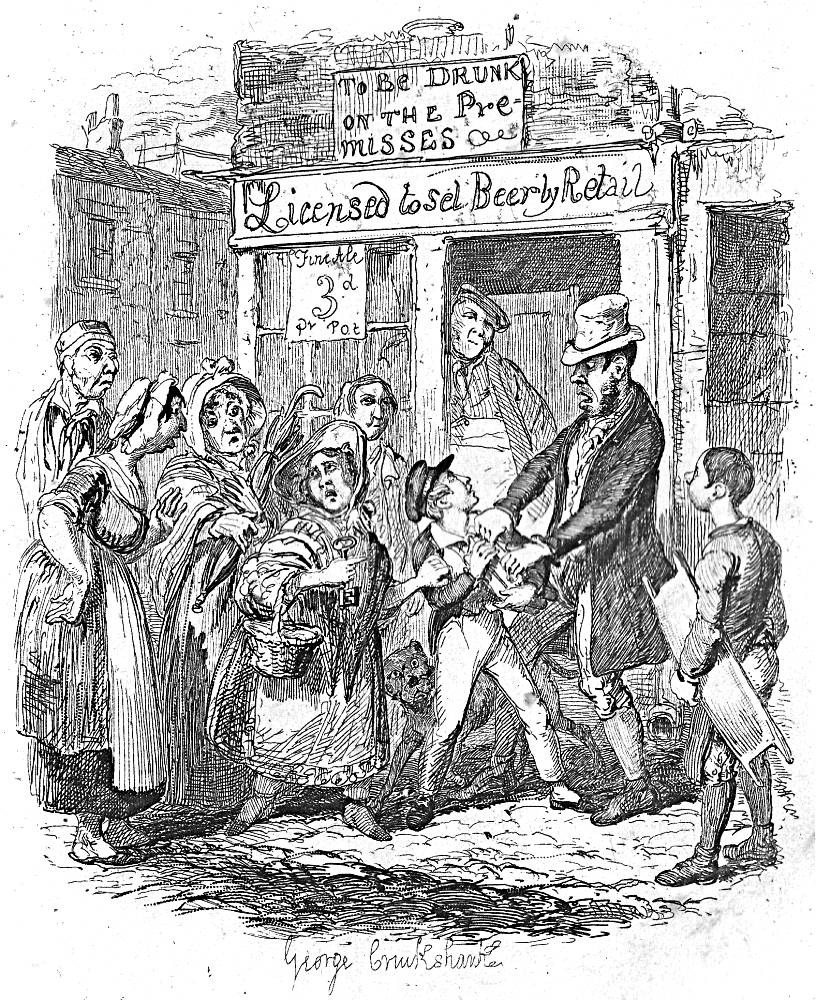

Cruikshank's illustrations of other liquor emporia, 1836-48

Left: The original Cruikshank engraving of a Regency "Gin Palace," The Gin Shop (1836). Centre: Cruikshank's cancelled plate from Sketches by Boz of a social club whose principal activities are smoking and drinking, The Free and Easy (8 February 1836). Right: Cruikshank's illustration of one of the boozey haunts of housebreaker Bill Sikes, a beer shop, in Oliver claimed by his affectionate friends (September 1837). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

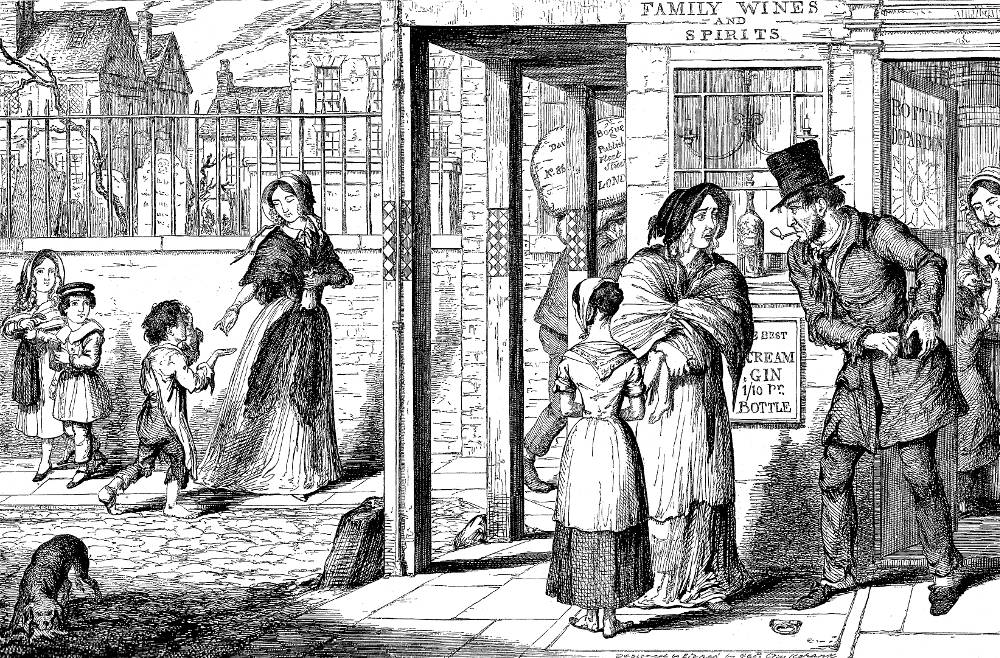

Above: Cruikshank's description of the outside of a drink-shop, juxtaposed against a cemetery, in The Bottle: Unable to Obtain Employment, They Are Driven by Poverty into the Streets to Beg, and by This Means They Still Supply the Bottle. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Above: Cruikshank's scene inside a gin palace, a place less refined than that he had depicted in Sketches by Boz, but in comparison with the beer-shop here, far more sedate. The customers in the 1848 illustration converse quietly over their drinks in Neglected by Their Parents, Educated Only in the Streets and Falling into the Hands of Wretches Who Live Upon The Vices of Others, They Are Led to the Gin Shop, to Drink at That Fountain Which Nourishes Every Species of Crime. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Whereas in illustrating Dickens and Ainsworth Cruikshank was compelled to attend to the descriptive details in the text and shape his conception of a drinking scene such as those in Sketches by Boz accordingly, much to his delight in this project for the Temperance Union he could control every detail, including the storyline, in his own "wordless" novella, The Drunkard's Children. In his pictorial telling of this sordid tale, Cruikshank had to rely only on repeating characters since, as opposed to his strategy in The Bottle, he could not repeat a single room to develop the action. Moreover, in the 1848 sequence he has made a number of the scenes are so crowded that the viewer sometimes has to search for the drunkard's son and daughter, upon whom the illustrator is relying to provide visual continuity."Since the captions for The Drunkard's Children are longer and of more importance than those for the first series, the second suite becomes more of a narrative. . . . . [and] gives scenes of lower-class Victorian life that were seldom portrayed in the arts of the period" (Vogler, p. 161).

In this 1848 sequel to The Bottle, Cruikshank employs a number of settings associated with proletarian London: the gin-palace in Plate I, the beer-shop here, the dancing-rooms, a three-penny lodging house, the criminal court of the Old Bailey, a lockup, the infirmary aboard a "hulk," or temporary, floating gaol, and one of the spans of New London or Waterloo Bridge. Whereas in only one of the scenes in The Bottle does Cruikshank offer an external view and depict a public space (Plate IV, below), the majority of the plates in the second sequence involve crowd scenes and public or communal places. The only intimate moment occurs in the lockup in Plate VI, when the brother, a convict felon, must bid his sister farewell before his transportation to Australia.

Charles Dickens on Drink and Poverty: Cause and Effect?

"We have sketched this subject," says Dickens, "very slightly, not only because our limits compel us to do so, but because, if it were pursued further, it would be painful and repulsive. Well-disposed gentlemen and charitable ladies would alike turn with coldness and disgust from a description of the drunken besotted men and wretched, broken-down, miserable women, who form no inconsiderable portion of the frequenters of these haunts; forgetting, in the pleasant consciousness of their own high rectitude, the poverty of the one and the temptation of the other. Gin-drinking is a great vice in England, but poverty is a greater; and until you can cure it, or persuade a half-famished wretch not to seek relief in the temporary oblivion of his own misery with the pittance which, divided among his family, would just furnish a morsel of bread for each, gin-shops will increase in number and splendour. If Temperance Societies could suggest an antidote against hunger and distress, or establish dispensaries for the gratuitous distribution of bottles of Lethe-water, gin palaces would be numbered among the things that were. Until then, their decrease may be despaired of." Dickens here glanced, and only carelessly, at the surface of the great question. This poverty which he deplored was the result of the drink. The Lethe-water would be unnecessary if the gin-and-water were stopped. Poverty, dirt, hunger, promote the publican’s trade; but this trade breeds the misery on which it thrives. The quartern which the father drinks, helps to raise a customer in his son, for the trade of the publican's son. More than ten years elapsed before this view of the Temperance question was destined to have complete sway and mastery over the genius of Dickens's illustrator; but already he saw deeper into it, because he looked more earnestly into it than the writer, who had not yet done with the comedy element of drunkenness. [cited by Blanchard Jerrold in "Epoch II: 1848-1878: Chapter 1, 'At Gillray's Grave,'"p. 84]

Related Material

- George Cruikshank and Charles Dickens

- The Gin-Shop

- The Parliamentary Report on Transportation (1838)

- "Great is thy power, O Gin" — Reynold's sermon on the harm it does to the poor

- London Gin Shops

- "Frauds on the Fairies" (1 October 1853)

- Temperance, Teetotalism, and Addiction in the Nineteenth Century

- Addiction in the Nineteenth Century

- Drunkedness and the ease of obtaining alcohol

- Alcohol and Alcoholism in Victorian England

- The Band of Hope Review

- Charles Dickens and Two Kinds of Punch, 1. The Beverage

Bibliography

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Cruikshank, George. The Drunkard's Children. A Sequel to "The Bottle." London: David Bogue, 1848.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

The Funny Songster. (1833)Songster Collection, British Museum (call mark C. 116 a 6-55). http://www.horntip.com/html/books_&_MSS/1830s/1833ca—1846_the_funny_songster__the_swells_night_guide_(HC)/index.htm

James, Louis. "An Artist in Time: George Cruikshank in Three Eras." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 156-187.

Jerrold, Blanchard. The Life of George Cruikshank. In Two Epochs. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. 2 vols. London: Chatto and Windus, 1882.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

Maxwell, William Hamilton. History of the Irish Rebellion in 1798; with memoirs of the Union, and Emmett's insurrection in 1803. Illustrated by George Cruikshank and E. P. Lightfoot. London: Baily Brothers, Cornhill, 1845. [Cruikshank, not mentioned on the title-page, provided etchings; he is more prominently mentioned on the title-page of the George Bell edition of 1884.]

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Meisel, Martin. Chapter 7, "From Hogarth to Cruikshank." Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1989. Pp. 97-141.

Mellby, Julie L. "More than 100,000 copies sold in the first few days." Graphic Arts: Exhibitions, acquisitions, and other highlights from the Graphic Arts Collection, Princeton University Library. Web. 13 April 2011. https://blogs.princeton.edu/graphicarts/2011/04/the_bottle.html

Scott, Derek B., David Gregory, and Ed Cray. Bawdy Songbooks of the Romantic Period: Items published by William West (1836-42). London: Taylor and Francis, 2011.https://www.bookdepository.com/Bawdy-Songbooks-Romantic-Period-Professor-Derek-B-Scott/9781848930292

Sutherland, John. "Lloyd, Edward." The Stanford Guide to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford U. P., 1989. P. 380.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Last modified 6 September 2017