The Pullen exhibition runs from 19 June 2018 until 28 October 2018. For more details, see offsite here. The first two images come, with thanks, from the Wellcome Institute's online collection, and the other photographs were taken by the author while visiting the exhibition. They are reproduced here by kind permission of the Gallery. Where feasible, the background has been digitally removed. Click on the images to enlarge them.

James Henry Pullen with his award-winning model, the Princess Alexandra, made for the wedding of the Princess and the then Prince of Wales in 1863. Credit: Wellcome Collection.

James Henry Pullen (1835-1916) was classified as an "idiot" in his own lifetime, but fêted for his ingenious and intricately carved and assembled models. Some of his work is on display at at the Langdon Down Museum for Learning Disability in Teddington, Middlesex, but beyond that, he is now little known. This summer, however, curators at the Watts Gallery in Compton, Surrey, are bringing him to the attention of a wider public. No one deserves such attention more. By exploring Pullen's life as an asylum inmate, and displaying some beautifully restored examples of his creations, the gallery has put on an amazing and often very moving exhibition about him.

The film presentation in the ante-room provides an introduction to the displays. Born into a large working-class family in Islington, Pullen was abnormally slow to speak, and indeed was never able to communicate properly. Like another of his brothers, he was given into care, admitted first to a school for "idiot" children, Essex Hall in Colchester, and later, with the rest of the children there, transferred to the newly opened Royal Earlswood Asylum in Redhill, Surrey. In an assessment from around that time, which is on display in large format separately, he was described as normal in appearance, if "florid" in colouring; and intelligent-looking. He was found to have a good memory, to be skilful in drawing, and to be keen to learn how to calculate. He was also observed to be emotionally "passionate." Despite all this, he spent the rest of his life in institutions. Significantly, he was later found to be extremely deaf.

Royal Asylum, Redhill, Surrey: panoramic view. Transfer lithograph by J.R. Jobbins after W.B. Moffat. Credit: Wellcome Collection.

Whether he should have been institutionalised in the first place is debatable. But at least the asylum was run on remarkably enlightened lines. It engaged its inmates in various activities, and Pullen for one was given a fine workshop and expected to earn his keep as a carpenter, designing and making furniture for the establishment. However, he was not prevented from working on his own projects. Some were for extra money. He would go round local pubs of an evening, matching his earnings at the asylum with money from the sales of his carved brooches, tie-pins and utensils. Examples of these are shown in one of the display cases. And apart from this sideline, he had another, more fulfilling one: concocting his extraordinary models, often but not always of ships.

Despite never having had an independent existence, Pullen became well known for this, even to the royal family; and some of his works went much further outside the asylum than he ever did, to be exhibited both at home and abroad: his huge model of a 40-gun man-o'-war, with which he is shown at the top right of this webpage, was so painstakingly accurate and impressive that it won a bronze medal at the International Exhibition in Paris of 1867. It should be said, though, that attention was focussed on such items in his own day less for their ingenuity and accomplished crafsmanship, than as proof of what could be achieved by the new institution's methods.

From left to right: (a) At the front of Pullen's State Barge (1886-87), carved ivory angels let down a gangway for a royal personage to board. (b) A crowned figurehead parts the waves for this Dream Boat, or Fantasy Boat, of about 1863, the only survivor of several like this that Pullen made. (c) The curious Rotary Sail Barge, possibly an invention for clearing canal-floors. On the wall behind is Pullen's "Pictorial Autobiography," shown on the left below.

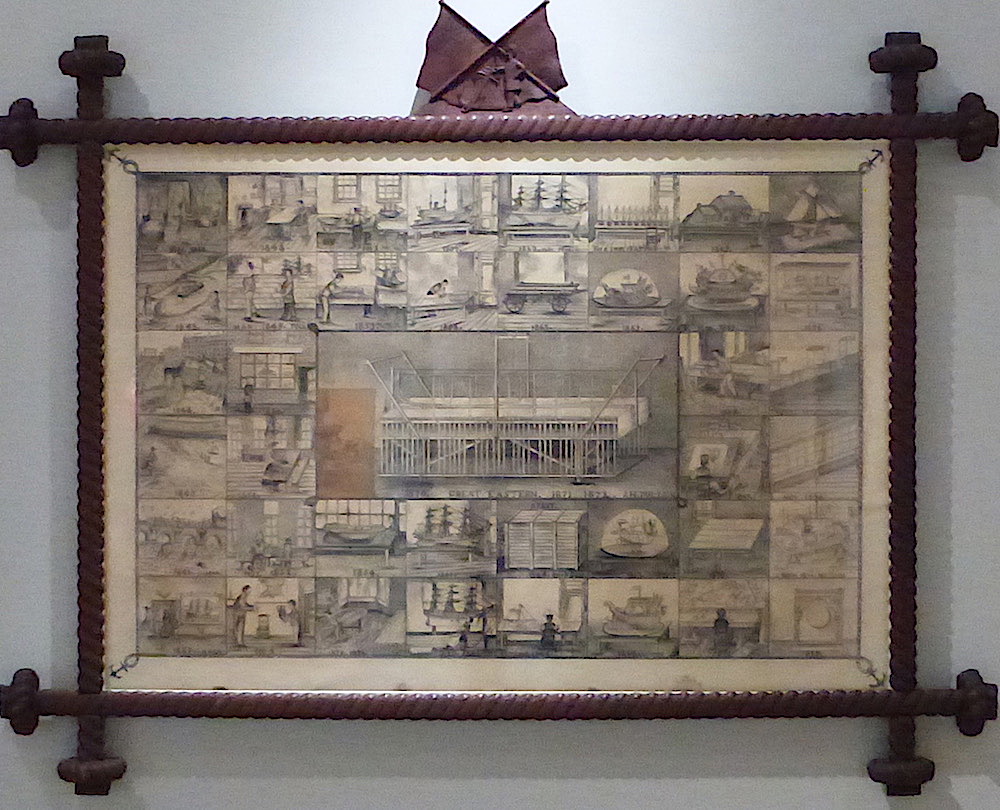

Helpful as it is, no background can adequately prepare visitors for the models themselves, or for Pullen's other work. A few steps down from where the film is shown, the main exhibition room is a revelation. The items range from his highly elaborate state barge seen on the left above, made from wood with ivory angels welcoming Queen Victoria on board — into what Pullen seems to have envisaged as a floating apartment for her. Oars are at the ready, fanning out at each side. As for the next Fantasy Boat, it is fit for a king, and supplied with wings for speed. Even more of a fantasy is the Rotary Barge, seen on the right above, with its circles of sails. These were meticulously restored and reassembled for the present exhibition. Also on display around the walls are some fascinating and detailed drawings, including the series of strip drawings which form Pullen's "Pictorial Autobiography," glimpsed behind the display case of the Rotary Sail Barge, above right, and shown more clearly below left — a touching testimony to his inner life as well as his outer one. Most of the little pictures show him at work on his models, and, at the centre, in pride of place and dominating everything, is the adjustable workbench he designed for himself, which could be raised or lowered according to need.

Left to right: (a) Pullen's "Pictorial Autobiography," with his magnificent workbench at its heart. (b) A reconstruction of Pullen's "Giant," facing the cast of Tennyson in Watt's sculpture studio. (c) Entry at the back of the model for someone to step into, to work the various mechanisms.

So was Pullen's life, in the end, all about his work? It might seem so. But perhaps the single most impressive exhibit is in the adjoining room, where G. F. Watts had his sculpture studio. Here, looking quite bizarre between the casts of Watts's statues of Tennyson and Physical Energy, stands a recreation of Pullen's huge "giant," a companion of his own making, on which he worked for decades. It had moving parts that could be worked from inside: he could make it blink its eyes, move its arms, and so on. He even made it capable of uttering sounds, by the operation of bellows — although with a "voice" too terrifying for children. Pullen, being deaf, would not have had a problem with it. It entertained people in his workshop, and went on asylum parades. It could even fire rockets. It was his friend, and the self of his own imagination, rolled into one.

The idea of having a living companion certainly entered Pullen's head. On his ventures into the locality he met a woman he liked, and even made known his intention of marrying her. But it seems that he was easily fobbed off with the gift of the smart, brass-buttoned uniform which he is seen wearing in his photograph — together with the suggestion that he could be appointed an admiral. However complex his models and normal his feelings, his mind, it seems, was easily manipulated. But then, having been institutionalised from a young age, that would have been natural enough.

Photograph frame for the Prince of Wales, whom Pullen met, and who supplied him with some costly materials.

Because his talents were exceptional, more is known about Pullen's life than about the lives of his fellow-inmates, and this information gives valuable insights into how such patients were treated. The fact that he was given a degree of freedom, was able to keep up with current technological developments, and was encouraged to express his own imagination in his own way, speaks well of the asylum. Less attention was paid to his emotional needs, and there seems to have been no idea yet of integrating such a person into the community. In that respect, Pullen's art can accurately be described as "outsider art," as the gallery's literature says (see headnote link). But displaying his artefacts at Compton is a first step towards drawing it into the mainstream, where it can stand beside the fantasy and science fiction works of contemporaries in different fields, like Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear, H. G. Wells, Richard Dadd and William Heath Robinson.

Visiting the Watts Gallery in the Watts Artists' Village, in the beautiful setting of the Surrey Hills, is always a memorable experience. This exhibition is only one part of what is on offer. But it is temporary, so go and see it while you can, as no pictures can do justice to it!

Created 27 June 2018