Photographs, captions, and commentary by the author. [You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one. Click on the thumbnails for larger pictures.]

The interior of St Giles' Roman Catholic Church, Cheadle, West Midlands. The spire of this Grade I listed building, designed by A. W. N. Pugin (1812-1852) and built from 1841-46, may be unusually tall for a church of modest size, but the real surprise is inside. Every inch of the interior is highly and intricately decorated, and glows with gilding. The idea was to reflect the richness of a spiritual heritage with which, Pugin felt, the English had lost touch. It was also to provide an appropriate setting for worship according to the old Sarum, or Salisbury, Rite. But there is something theatrical here, as well, no doubt carried over from those early days when Pugin designed stage sets for Covent Garden. The spiritual fervour of a convert, combined with this sense of drama, and a thorough knowledge of medieval ecclesiastical forms and fittings, has produced something unique: "In its elaboration, its Englishness and its predominant symbolism ... it was the epitome of Puginism" (Hill 359).

The Nave

Left to right: (a) The nave from the west end, showing the length of the church. (b) The oak roof. (c) The Chancel arch, with the painting of the Doom, that is, the Last Judgement, above it.

The five-bay nave is described in the listing text as having "octagonal columns painted in chevron pattern; pointed moulded arches, with carved lions in spandrels; large studs on corbels [with] scissor-brace collared trusses, fretwork in apices, single purlins and large curved windbraces"; Pugin himself described the roof proudly as being "framed entirely of English oak, all the beams, rafters, braces, &c, being open to the ceiling, and carved and moulded; each principal rests on a stone corbel, representing an angel playing on some musical instrument" (Lord Shrewsbury's New Church, 9). The depiction of the "Doom" above the chancel arch was a typical medieval feature, later found in other Gothic Revival churches (such as G. E. Street's St. James the Less in London). It was painted on canvas by the Swiss artist Edward Hauser (1807-1864), and has suffered a little from the passage of time. Poignantly, a daughter of the Earl of Shrewsbury, who had died in in 1840, is included among a group of young women in white robes being welcomed to heaven on the left-hand side (see Fisher 189).

Left to right: (a) One of the lion's head carvings. (b) The cross above the Rood Screen. (c) A door and its highly decorated surround.

The lions' heads are appropriate — they could allude to the winged lion of Revelations, which features, for example, in William Burges's St Mary, Studley Royal, Yorkshire — but also to the heraldic lions of the Shrewsbury family. Everything is packed with meaning here. The cross, of course, is the devotional focus: "From the centre of the loft rises the great rood and crucifix, with the attendant images of our Blessed Lady and St. John, which are placed on pedestals united to the foot of the rood with rich tracery. The cross is crocketed at the sides, and terminates at the extremities with quatrefoils, containing emblems of the Evangelists, and surrounded with foliage (Pugin, "Lord Shrewsbury's New Church," 10-11). It was carved in George Myers' workshop in Lambeth (Fisher 188). Although Pugin's ideal was to work with local craftsmen, this was only possible up to a point. The painted decoration was partly by the Earl of Shrewsbury's decorator, Thomas Kearns, but the later and more intricate work was by the more skilled London decorators, J. C. Crace (see Fisher 170).

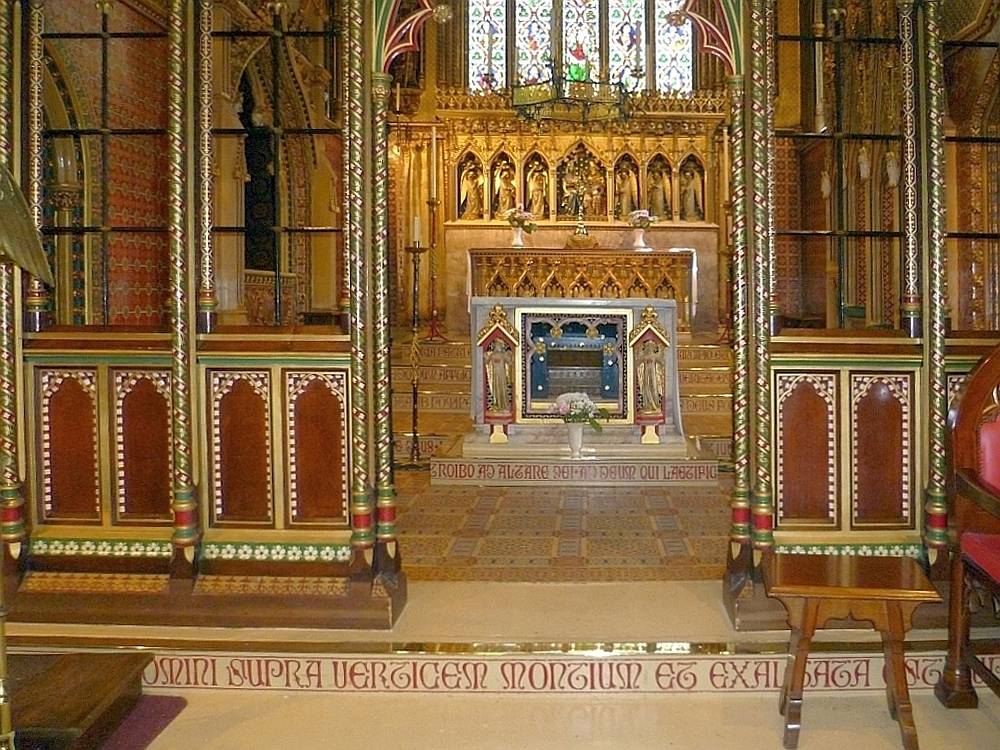

The Chancel

The chancel, says Pugin, "is twenty-seven feet in length, and nearly the same width as the nave. The ceiling is of oak, arched and divided into panels by moulded ribs, with carved bosses at every intersection," its panels "powdered with gilt stars, with monograms of the holy name in the centres, surrounded by radiating borders" (Lord Shewsbury's New Church, 12). It can be seen in the picture of the Rood, in the centre of the row of pictures above. As for the walls, these are "entirely gilt; angels bearing scrolls with Scriptures from the Te Deum. Benedictus, &c., are painted at intervals, encircled by garlands, which are connected by a continuous diaper of quatrefoils and foliage" (Lord Shewsbury's New Church, 12). Everything here glows and dazzles.

Left: The high altar and reredos. Right: The Easter Sepulchre painting in the chancel, on a metal panel, also by Eduard Hauser (see Fisher 195).

The intricate sculptural work of the high altar and reredos was by Thomas Roddis, a stonemason from Sutton Coldfield who moved to Cheadle at this time, and whom Pugin called a "faithful & Laborious man" (Collected Letters 2, 465). Pugin describes the alabaster altar that he carved for the chancel, the sacred point to which the whole nave and chancel tends, as having a "front ... filled with angels seated on thrones under elaborate tabernacle work, playing diverse instruments, relieved by gilding and colour." The reredos above "represents the coronation of our Blessed Lady. This subject fills the centre compartment, while three niches on either side contain angels bearing thuribles and tapers," whilst above that are more angels carved along the stringcourse, topped by what Pugin calls "perforated brattishing level with the syl of the east window." Every aspect of church furnishings had been studied and reproduced here, down to the soft furnishings: "At either end metal brackets support curtains of tapestry with cipherings" (Lord Shrewsbury's New Church, 12). Hauser's painting under its intricately carved and gilded ogee arch (notice all the St George's shields) is specifically for an Easter ritual in the old Sarum liturgy (see Fisher 195).

(a) The chancel tiling. (b) The sedilia, or seats for the officiating priests. Just before these is a small but similarly canopied piscina or basin for the washing of hands, and of the sacred vessels. (c) One side of the medieval corona or circular candelabra, showing words ("miserere nobis qui" or "have pity on us who") from the text that encircles it.

The nave tiling is from Wedgwood, but the Minton tiling in the chancel is more elaborate and colourful, making the area even more brilliant. Herbert Minton became a friend of Pugin's, and later visited him at Ramsgate (see Hill 43). As Pugin says, the sedilia which make another notable feature here "are elevated one above the other on the three steps approaching the platform of the altar." He continues, "The respective emblems of priest, deacon, and sub-deacon, are carved in panels at the back of the seats, and the whole is surmounted by elaborate canopies and pinnacles" (Lord Shrewsbury's New Church, 12). This is immediately opposite the sepulchre for the Easter service. The stained glass that Pugin designed for the church is discussed separately, but the east window here, showing the genealogy of Christ, adds immeasurably to the play of light and colour as well as the spiritual meaning of the chancel.

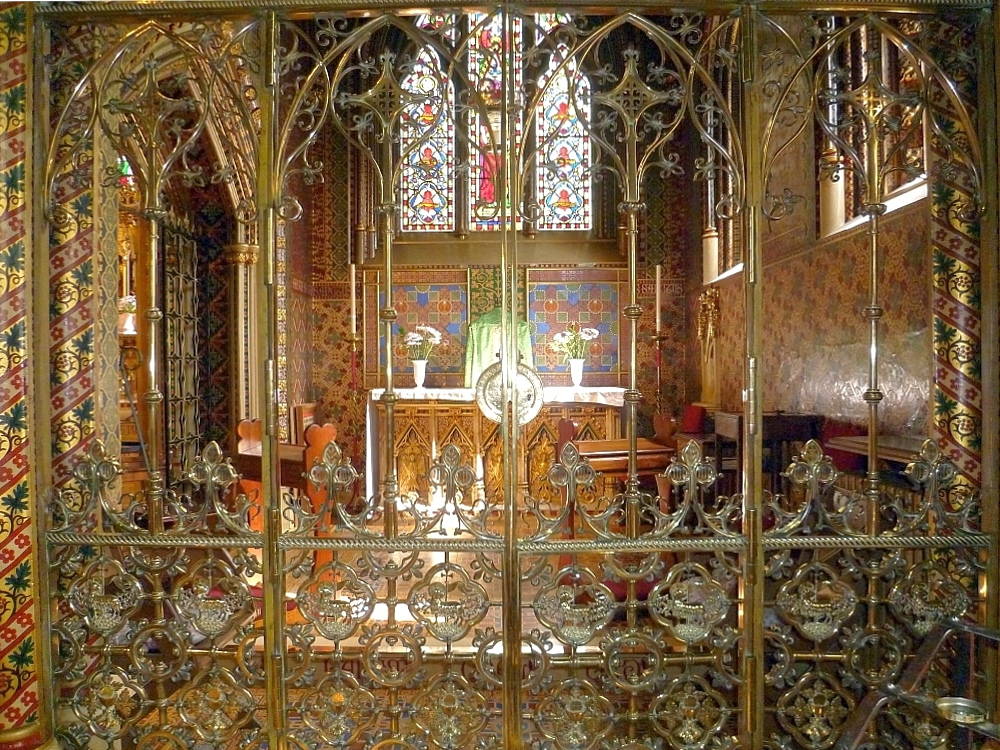

Blessed Sacrament Chapel

"The chapel of the Blessed Sacrament is divided from the south aisle by a stone arch and an open screen of wrought brass. The lower panels are filled with chased and perforated work, representing chalices, with the blessed sacrament and lambs alternately, and a pierced cresting surmounts the upper part, rising into crosses.... Although light in appearance, this screen is of immense weight, and has occupied nearly two years in execution," writes Pugin. Like other metalwork in the church, it was executed by Hardmans of Birmingham. Of the liturgical inscriptions in front of the arch, and below each step inside the chapel, only the one below the top step can partially be glimpsed here: "Panem de coelo dedit eis" or "Thou hast given us bread from Heaven." Texts, as seen above at the entrance to the chancel, were another aid to devotion.

Church Fittings

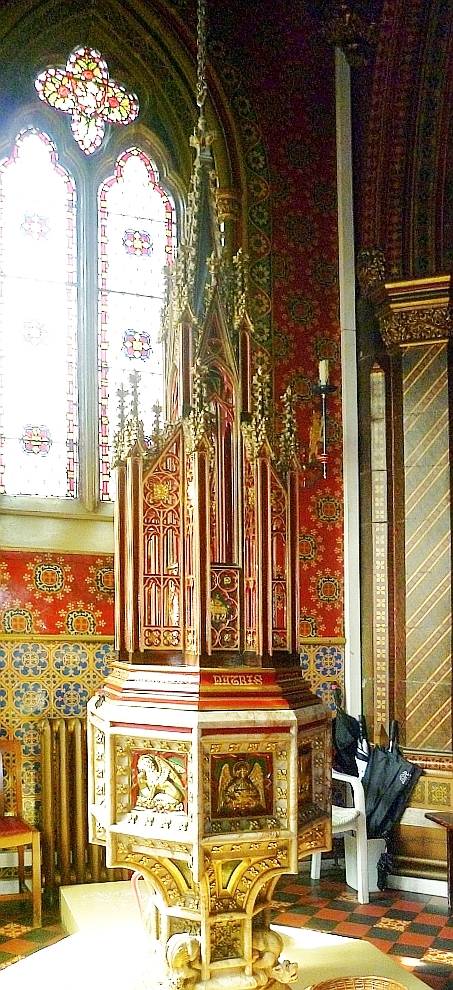

Left to right: (a) The pulpit. (b) The pulpit from the other side. (c) The font with cover. (d) Closer view of the font carving.

Again, Pugin himself gives the best accounts of the pulpit and font. "The pulpit, which joins the Lady Chapel, is octagonal in plan. The four sides facing the nave contain subjects representing St. John the Baptist preaching in the wilderness; towards the chapel the three great friar preachers, St. Francis, St. Dominic, and St. Bernardin. It is ascended by a staircase in the sacristy, leading up through a door in the east wall" (Lord Shrewsbury's New Church 10). Roddis carved it out of one piece of local stone (Noszlopy and Waterhouse 215). As for the hexagonal alabaster font, ascribed to Roddis as well (Noszlopy and Waterhouse 215), the "four monsters, or dragons" at the base are "emblematic of sin destroyed by the sacrament of Baptism. The bowl is surrounded by quatrefoils, containing emblems of the four Evangelists, and angels, bearing crowns. The cover is framed of oak, and forms a central canopy, supported by eight flying buttresses and pinnacles, and surmounted by a finial, to which the chains are attached, for the convenient raising and lowering of the same" (Lord Shrewsbury's New Church 10). Roddis also carved the lovely altars in the Blessed Sacrament Chapel and the small Lady Chapel at the end of the north aisle — Pugin topped the latter with an equally finely carved late medieval oaken reredos, of Flemish provenance.

Conclusion

The Flemish reredos, that the Earl of Shrewsbury had wanted for St John's in Alton, but which Pugin persuaded him would be better here (see Fisher 185).

Despite such touches as the chancel corona and the Lady Chapel reredos, it is hard to imagine any medieval church looking quite like St Giles'. As Rosemary Hill says, it stikes us now as "a full-blown work of high romantic art" (360). It is easier to imagine the impact of such a church on a market town where many worked in local mines, or at looms. Following the consecration on the previous day, the elaborate opening ceremony on St Giles' Day (1 September) 1846 caused a huge stir, as a whole range of important personages — diplomats and dignitaries hosted by the Earl at Alton Towers, top church people including the Archbishop of Damascus with his interpreter, and the recent convert to Catholicism, John Henry Newman, as well as people from the art world, such as Charles Barry and Clarkson Stanfield — all descended on Cheadle. John Hardman led the the choir of Birmingham's St Chad's for the introit, Bishop Wiseman (not yet Cardinal) spoke at Vespers, and so on. The Morning Post of Saturday 5 September 1846 reported that the new church was "one of the most exquisitely beautiful structures in the kingdom," and the reporter in Freeman's Journal in Ireland, on the same day, talked of its "chaste magnificence." It is still a place of pilgrimage, arguably Pugin's greatest, and certainly his most complete and influential work.

The fine brass lectern, possibly by the Hardman firm though not included in the long list of items drawn up for Hardman in December 1844 (see Fisher 205).

Related Material

- St Giles' interior, as shown in Plate of Pugin's Present State of Ecclesiastical Architecture

- St Giles' chancel, as shown in Plate of Pugin's Present State of Ecclesiastical Architecture

- St Giles', Cheadle (Exterior)

- St Giles', Cheadle: A Gallery

- Stained glass in St Giles'

- St Joseph's Convent and Primary School, Cheadle (associated buildings)

Bibliography

19th Century British Library Newspapers (Gale). Web. 26 November 2012.

Fisher, Michael. "Gothic For Ever": A. W. N. Pugin, Lord Shrewsbury, and the Rebuilding of Catholic England. Reading: Spire, 2012.

Hill, Rosemary. God's Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain. London: Penguin, 2007.

Noszlopy, George T., and Fiona Waterhouse. Public Sculpture of Staffordshire and the Black Country. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2005.

Pugin, A. Welby. Account of the church in Lord Shrewsbury's New Church of St Giles, in Staffordshire: Being a Description of the Edifice.... London: Charles Dolman, 1846. (Free book) Google Books. Web. 26 November 2012.

____. The Collected Letters of A. W. N. Pugin, Vol. 2. 1843-45. Ed. Margaret Belcher. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

"Roman Catholic Church of St Giles." British Listed Buildings. Web. 26 November 2012.

Last modified 7 February 2020