[This is a shortened version of an article that appears in Victorian Review 37.1.]

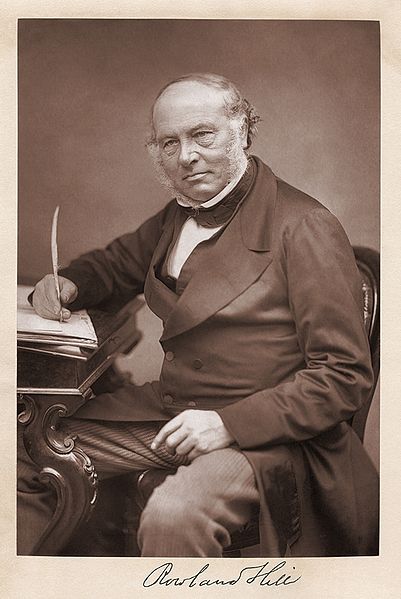

Left: Sir Rowland Hill — a photograph with Hill's signature. Middle left: Rowland Hill by Edward Onslow Ford, R. A. This statue stands outside the old Post Office headquarters on King Edward Street, London EC1. Middle right: Sir Rowland Hill by Thomas Brock, K.C.B., R.A. This monument is in Kidderminster. Right: Rowland Hill by William Theed. This monument is in Manchester. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

Postal reformer Sir Rowland Hill (1795-1879) analyzed the British postal system from the vantage point of an enlightened outsider and published four editions of his epic Post Office Reform: Its Importance and Practicability (1837). Hill’s pamphlet set in motion the reformation of the unwieldy, expensive United Kingdom postal service, resulting in the adoption of the The Penny Post in 1840. All mail weighing up to ½ ounce could travel anywhere in the UK for only a penny.

Hill was born into a family of enlightened educators during an age notorious for public school brutality and rote memorization, as Charles Dickens memorably satirizes in his characterization of Thomas Gradgrind in Hard Times (1854). Rowland's liberal and forward-thinking father, Thomas Wright Hill, founded a school that allowed its pupils to participate in self-governance and instruction. At twelve, Rowland became a teacher at Hazelwood School, but he centered his reform efforts on the postal system. In 1826, he suggested improvements for equipment and operations. In 1836, Hill worked with Robert Wallace, MP, who used his franking privilege — postmarks granting Members of Parliament and the Queen free carriage of mail (which the Penny Post, in turn, abolished) — to send Hill copious official government and Post Office documents. Hill systematically analyzed these materials, filling his influential pamphlet with facts and figures, supplemented by moving stories of broken kinship ties and deprivations due to high postage.

Hill’s Penny Post plan was revolutionary. In the early nineteenth century, letter writing was the only way to communicate with those living at a distance. Prior to 1840, the post was expensive; for the working class, a letter could cost more than a day's wage. Leaving home for work, emigration, or travel often meant losing contact with friends and family. In Post Office Reform, Hill strategically equates cheap postage with an “unobstructed circulation of letters” that would lead to “religious, moral, and intellectual progress;" as Hill advances, “When it is considered how much the religious, moral, and intellectual progress of the people, would be accelerated by the unobstructed circulation of letters . . . the Post Office assumes the new and important character of a powerful engine of civilization” (8). The Victorians envisioned cheap postage as a way to restore kinship ties, stimulate trade, and improve science, education, literacy, and morality.

Among the first actions Victoria took when she ascended to the throne in 1837 was to appoint a Select Committee on Postage, chaired by Wallace and charged to look into the post with a view towards postal rate reduction., On August 17, 1839, Queen Victoria gave royal assent to the Postage Duties Bill. On opening day of the Penny Post, January 10, 1840, people cheered for Rowland Hill.

Hill initially received an appointment to the Treasury to oversee the Penny Post transition. To signal prepayment of postage, Hill invented stationery (called Mulreadies after William Mulready, RA, who designed them) showing a glorious postal outreach and postage stamps. Public rejection of Mulreadies was immediate, giving rise to caricature envelopes that essentially killed the Mulready, which the Post Office withdrew in 1841. In contrast, the stamp featuring a bust of young Queen Victoria was an instant success. In Post Office Reform, Hill defines postage stamps as “a bit of paper just large enough to bear the stamp, and covered at the back with a glutinous wash” (45). The stamp quickly became a model for other nations: in 1843, Brazil and the Swiss Cantons of Geneva and Zurich issued stamps, and the United States swiftly followed in 1847.

Hill’s service to the Treasury ended in 1842; with the election of the Conservative party, Hill was unseated. However, in 1846, Hill returned to the Post Office as secretary to the postmaster general and, in 1854, he became secretary to the Post Office, a position he held until his retirement in 1864. During his lifetime, Hill had plenty of supporters and plenty of critics. The British people, in gratitude for his Penny Post plan, granted Hill countless honors including knighthood in 1860, an honorary Oxford degree, designation of Freeman from the city of London, and burial in Westminster Abbey. Punch, the Victorian New Yorker, even dubbed him “Sir Rowland Le Grand” in a John Tenniel cartoon that appeared on March 19, 1864 upon the occasion of Hill’s retirement.

Many of the works about Hill published in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries lack objectivity since their authors were Hill himself and close kin — e.g. daughter Eleanor, son Pearson (also his personal assistant), and nephew George Birkbeck Hill, who finished Hill’s memoir after his death. Following his retirement, Hill spent the last 15 years of his life “given over to the preparation of an elaborate autobiography — the apologia ” of his efforts and of his place in postal reform (Robinson 366n29), which Martin Daunton also laments: “the development of the Post Office is now viewed almost entirely through the distortions of Hill’s voluminous writings, works of self-justification which do not provide an objective view of the reforms introduced in 1840” (3-5). Successive postmasters general during Hill’s tenure complained of his “peremptory and high-handed” leadership style (Daunton 5), as did Anthony Trollope, a Post Office employee for over thirty years and a vocal “anti-Hillite.” However, Trollope recognized Hill’s achievement, and his satire of letter-obsessed spinster cousins, Iphy and Phemy Palliser in Can You Forgive Her (1865), fictionalizes the impact of Hill’s plan on Victorian daily life: “Free communication with all the world is their motto, and Rowland Hill is the god they worship” (I: 237-38).

Many blessed Hill as the originator of the Penny Post. In her laudatory 1843 letter to Thomas Wilde, MP, Harriet Martineau — an avid Hill supporter — even questions whether one person ever before encompassed “the functions at once of the pulpit, the press, the parent, the physician, and the ruler — ever in so short a time benefited his nation so vastly, or secured so unlimited a boon to the subjects of an empire” (48). Now largely forgotten, the once eminent Sir Rowland Hill set in motion a revolutionary postal network for sending letters of business and friendship that allowed Victorians to transcend geographical boundaries and changed postal services around the world.

BIbliography

Daunton, M. J. Royal Mail: The Post Office Since 1840.London: Athlone Press, 1985.

Golden, Catherine J. Posting It: The Victorian Revolution in Letter Writing. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2009.

Hey, Colin. Rowland Hill: Genius and Benefactor 1795-1879. London: Quiller Press, 1989.

Hill, Rowland. Post Office Reform: Its Importance and Practicability. 2nd edition. London: Charles Knight, 1837.

Hill, Rowland, and George Birkbeck Hill. The Life of Sir Rowland Hill. 2 vols. London: De La Rue, 1880.

Martineau, Harriet. "Letter to Sir Thomas Wilde, M.P." The Post Office of Fifty Years Ago. By Pearson Hill. London: Cassell, 1887. 44-48.

Robinson, Howard. The British Post Office: A History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1948.

Smyth, Eleanor C. Sir Rowland Hill: The Story of a Great Reform Told By His Daughter. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1907.

Trollope, Anthony. Can You Forgive Her. 1865. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Last modified 25 March 2012