he Introduction to this well-presented book defines Public Sculpture as any statuary which is outdoors. Works inside churches, schools, town halls etc are generally excluded. Faced with so vast a subject, the author has chosen a thematic approach rather than a geographical one. Thus successive chapters discuss monarchy, war heroes, war memorials and so on. Most works in the past fifty years are covered in the last two chapters, rather blandly entitled ‘Sculpture in Public’ and ‘Public Art’. This arrangement generally works well, although there are some overlaps: Philip Jackson’s Bomber Command Memorial (2012) is described twice, on pages 111 and 222.

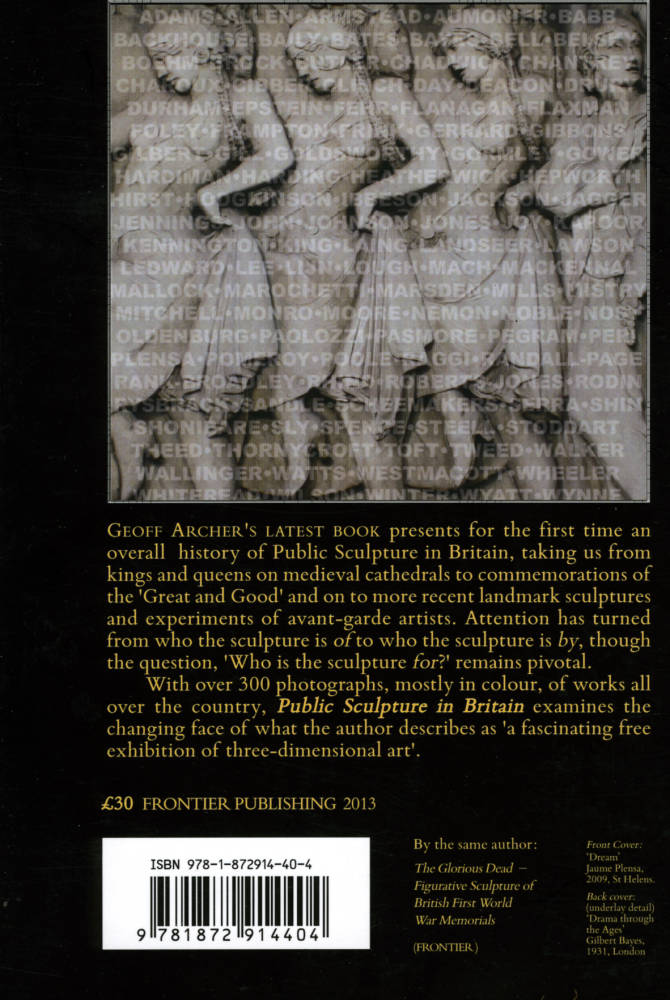

The front and back covers of the book under review and a sample page. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

The chapter on Monarchy begins with the twelve Eleanor Crosses erected by Edward I (1290) and ends with the equestrian Queen Elizabeth II in Windsor Great Park (Philip Jackson 2003). Curiously, the photograph of this elegant work shows only the back view of the royal head. The author teasingly suggests that the controversial fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square would in due course be the ‘obvious location’ for a national memorial to Queen Elizabeth.

Left photographs each of the The Albert Memorial and the Victoria Memorial. [Photographs from the Victorian Web and not the book under review. Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Full accounts are given of the Albert Memorial (Gilbert Scott and others) and the Victoria Memorial (Thomas Brock). The latter has been praised by Ben Read as ‘one of the supreme achievements of the New Sculpture’ and criticised by Susan Beattie as ‘an astonishing assemblage of echoes of the monuments of others’. The author concludes ‘it is possible to see [Brock’s] ‘reminiscences’ as positive and intentional and certainly no different from the strategies of other New Sculptors’.

Although Nelson and the Duke of York have their Columns, many statues of Military Heroes from Wellington (Chantrey 1839) to Earl Haig (Alfred Hardiman 1937) are equestrian. With the end of cavalry, this tradition has ceased and the generals of World War II have to be satisfied with standing figures of varying quality, the most recent being Air Chief Marshal Park (Les Johnson 2010). Mr Archer quotes Coventry Patmore’s “Shall Smith Have a Statue?”, with its warning against excessive haste in erecting memorials to the recently deceased, as their fame may be short-lived.

The reigns of Victoria and Edward saw an impressive flood of statues of the Great and the Good. Modern dress was a problem, and sculptors often avoided the dreaded ‘coat and trousers’ (as in Richard Belt’s Lord Byron 1880) by clothing their subjects in ceremonial robes (Disraeli by Mario Raggi 1883) or in academic dress (Gladstone by James Pittendrigh McGillivray 1917). The fact that statues by lesser-known sculptors like Belt, Raggi and McGillivray are illustrated shows that this book does not just cover well-trodden paths.

Left two: Mario Raggi's: Benjamin Disraeli (Lord Beaconsfield) . Right two: Albert Gilbert's Eros [Photographs from the Victorian Web and not the book under review. Click on these images for larger pictures.]

As early as 1893 Alfred Gilbert’s Shaftesbury Memorial (better known as Eros) offered a symbolic alternative to the traditional figurative style, but memorial committees were unconvinced. Jacob Epstein’s modernist works like his Hudson Memorial (1925) aroused controversy, but even he eventually mellowed, as shown by his Field Marshal Smuts (1956). In the last twenty years conventional statues of the Great and the Good (now called Celebrities) have ‘enjoyed something of a renaissance’, with Matt Busby (Philip Jackson 1996) and Eric Morecambe (Graham Ibbeson 1999).

The 1914-18 War produced three notable War Memorials – the Cenotaph (Edwin Lutyens 1920) being the most famous, the Royal Artillery Memorial (Charles Jagger 1925) the most powerful and the ‘anachronistic and irrelevant’ Machine Gun Corps Memorial (Francis Derwent Wood 1925) the most controversial.

Left: (a) Jagger's Royal Artillery Memorial. Right: Derwent Wood's Machinegun Corps Memorial [Photographs from the Victorian Web and not the book under review. Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Fewer monuments appeared after the 1939-45 War, the most noteworthy being the Armed Services Memorial (Ian Rank-Broadley 2007). Mr Archer may be too imaginative in comparing its imagery to Michelangelo’s Pieta, but he rightly notes: ‘….in engraving the names of the dead on its walls, the Armed Forces (sic) Memorial ….meets a very real, and unfortunately continuing need ’.

The story of Architectural Sculpture begins with the medieval west front of Wells Cathedral and ends with Walter Ritchie’s carved brick relief Seeds and Flowers (1986) in nearby Bristol. The relationship between architects and sculptors is often tricky, but a notable partnership was that between Charles Holden and the sculptors Jacob Epstein (Night and Day), Eric Gill (South Wind) and Henry Moore (West Wind) for the London Underground building (1929). It is interesting to compare their Modernist style with the Art Nouveau Queen of Time) by Gilbert Bayes for Selfridges store just a year earlier (1928).

Chapter VI surveys significant public displays of sculpture, including the 1948 Battersea Park Exhibition and the 1951 Festival of Britain. The 1953 Tate exhibition of entries for the Unknown Political Prisoner competition was ignored by the popular press until a Hungarian refugee destroyed Reg Butler’s winning maquette. Other examples of extreme reactions are Raymond Mason’s Forward, unveiled by the Queen in Birmingham in 1991 and destroyed by fire in 2003; and Rachel Whiteread’s House, awarded the Turner Prize in 1993 and demolished in 1994.

Mr Archer covers an extremely wide range of works, including all the most famous memorials, while successfully avoiding a series of lists. Public art has always been controversial, and he gives lively accounts of such disputes. As a result, he has produced a very readable and enjoyable book. He concludes with this thought: ‘the challenge for the sculptor [is] to be both original and thought-provoking while pleasing, or at least not actually antagonising, the public…. Not all have been successful…. but our towns and cities would be far less exciting places without their continuing efforts’. Let us say ‘Amen’ to that.

Bibliography

Archer, Jeff. Public Sculpture in Britain – A History. Kirstead, Norfolk: Frontier Press. 2013. ISBN (3)978.1.872914.40).4; 416 pp; pb.

Last modified 30 March 2014