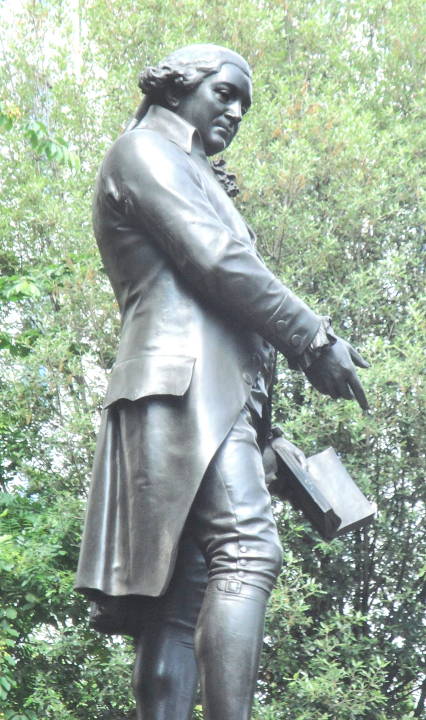

Robert Raikes. Sir Thomas Brock. Bronze. 1880. Victoria Embankment Gardens, London. According to Leslie Stephen's entry for Robert Raikes (1735-1811) in the 63-volume first edition of Dictionary of National Biography, the social reformer often credited with originating the Sunday School Movement, was born at Gloucester on 14 September 1735, the son of Robert Raikes, who founded The Gloucester Journal, “one of the oldest country newspapers. . . . Robert, [who] succeeded to the Gloucester business on his father's death, . . . was an active and benevolent person, and in 1768 inserted in his paper an appeal on behalf of the prisoners in Gloucester. The gaols were marked by the abuses soon afterwards exposed by Howard. No allowance was made for the support of minor offenders, and Raikes says that some of them would have been starved but for 'the humanity of the felons,' who gave up part of their rations.

Concerned with the lack of training or education for children, he began to promote Sunday schools.

Commentary by Leslie Stephen in The Dictionary of National Biography

Various accounts are given of the circumstances which led to the action which made him famous. He mentions an interview (traditionally placed in St. Catherine's meadows) with a woman who pointed out a crowd of idle ragamuffins. He is also said to have taken a hint from a dissenter named William King, who had set up a Sunday school at Dursley. Cynics reported that Raikes made up his newspaper on Sundays, and was annoyed by the interruption of noisy children outside when he was reading his proofs. In any case, he spoke to the curate of a neighbouring parish, Thomas Stock (1749-1803), who had started a Sunday school at Ashbury, Berkshire. Raikes and Stock engaged a woman as teacher of a school, Raikes paying her a shilling and Stock sixpence weekly. Stock drew up the rules. Raikes afterwards set up a school in his own parish, St. Mary le Crypt, to which he then confined his attention. Controversy has arisen as to the share of merit due to Raikes and Stock. It must no doubt have occurred to many people to teach children on Sunday. Among Raikes's predecessors are generally mentioned Cardinal Borromeo (1538-1584), Joseph Alleine, Hannah Ball, and Theophilus Lindsey. Raikes's suggestion fell in with a growing sense of the need for schools, and became the starting-point of a very active movement.

His first school was opened in July 1780. In November 1783 he inserted in his paper a short notice of its success, without mentioning his own name. Many inquiries were consequently addressed to him. An answer which he had sent to a Colonel Townley of Sheffield was published in the Gentleman's Magazine in 1784, and a panegyric, giving a portrait and an account of his proceedings, was in the European Magazine of November 1788. The plan had been quickly taken up at Leeds and elsewhere. Raikes's friend, Samuel Glasse, preached a sermon in 1786 at Painswick, Gloucestershire, on behalf of the schools there, and stated in a note that two hundred thousand children were already being taught in England. The bishops of Chester and Salisbury (Porteus and Shute Barrington) gave him their approval. William Fox , who had been trying to start a larger system, thought Raikes's plan more practicable, and, after consulting him, set up in August 1785 a London society for the establishment of Sunday schools. Jonas Hanway and Henry Thornton were members of the original committee, and ten years later the society had sixty-five thousand scholars.

Wesley remarks in his journal of 14 July 1784 that he finds these schools springing up wherever he goes. He published a letter upon them next year in the Arminian Magazine, and did much to encourage them among his followers. They were introduced into Wales by Thomas Charles of Bala, in 1789, and spread into Scotland, Ireland, and the United States. They had attracted attention outside of the churches. Adam Smith, according to one of Raikes's letters in 1787 (GREGORY, p. 107), declared that no plan so simple and promising for the improvement of manners had been devised since the days of the apostles. At Christmas 1787 Raikes was admitted to an interview with Queen Charlotte, who spoke favourably of the plan to Mrs. Trimmer, and Mrs. Trimmer started schools, which were graciously visited by George III. Hannah More followed Mrs. Trimmer's example by starting similar schools in Somerset in 1789. . . .

Raikes . . . died at Gloucester, 5 April 1811, and was buried in the church of St. Mary le Crypt, where there are monuments to him and his parents. His widow died, aged 85, on 9 March 1828. They had two sons and six daughters.

Raikes is accused of excessive vanity; but he seems to have been a thoroughly worthy man. His merit in the Sunday-school movement appears to have been not so much in making any very novel suggestion as in using his position to spread a knowledge of a plan for cheap schools which was adapted to the wants of the day. He very soon came to be regarded as the 'founder of Sunday schools,' but does not appear to have himself ignored the claims of his co-operators. A 'jubilee' was held in 1831, at the suggestion of James Montgomery, to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the movement (really the fifty-first), when it was said that there were 1,250,000 scholars and one hundred thousand teachers in Great Britain. A centenary celebration was also held in 1880, when Lord Shaftesbury unveiled at Gloucester the model of a statue of Raikes, intended to be placed in the cathedral. It has never been executed. Another statue was erected upon the Victoria Embankment.

Related material

Photographs and captions by Robert Freidus. formatting by George P. Landow. You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one. [Click on all images for larger pictures.]

Bibliography

Byron, Arthur. London Statues. London: Constable, 1981.

Stephen, Leslie. “Raikes, Robert.” Dictionary of National Biography. Eds. Leslie Stephen and Sidney Lee. 63 vols. London: Smith, Elder: 1885-1900. Internet Archive/Online Books Page (U. of Pennsylvania). Web. 14 June 2011.

Read, Benedict. Victorian Sculpture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982.

Last modified 11 June 2017