The historic photographs come, with thanks, from the online gallery of the Wellcome Library, London, and my be reused with attribution under the Creative Commons Licence. The recent photograph is by the present author, and may be used without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer or source, and (2) link your document to this UR, or cite the Victorian Web in a print document. [Click on all the images to enlarge them.]

Portrait of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. Source: The Wellcome Library, London.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836-1917) was one of those select few Victorians who, by their campaigning and example, utterly transformed the lives of British women. No one could have predicted this from the bare facts of her early background. She was born in Whitechapel, a poor area of East London, in 1836, the second in a large family of children born to a pawnbroker. Yet her father Newson was no ordinary pawnbroker. The son of a noted family of Suffolk agricultural engineers, he was simply running the business for his father-in-law. In 1838, he decided to take his family back to Suffolk. Here, he soon bought up a corn and coal merchant's concern, and in 1854 launched what would become The Maltings at Snape, near Aldeburgh, now a popular "heritage" attraction on the Suffolk coast, and the venue of the famous Aldeburgh Music Festival. Newsom and his wife Louisa's fortunes rose steadily now, especially since his interests extended to shipping and the railways. After a few years at home with a governess, in 1849 his daughter Elizabeth was sent to a carefully chosen boarding school in Kent. The school was run by Robert Browning's aunts, and seems to have introduced her to progressive ideas. It certainly took her nearer the city of her birth again.

These were the first three women to become fully accredited doctors. Anderson is flanked by Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1901), whose campaigning inspired her, and Sophia Louisa Jex-Blake (1840-1912), who paved the way for other women to gain a medical education without exploiting loopholes in the old system. She too founded a women's hospital, in Edinburgh, and a school of medicine there as well. Source: The Wellcome Library, London.

It was in London, in the later 50s, that Elizabeth met Emily Davies, the early feminist and future co-founder (with Barbara Bodichon) of Girton College, Cambridge. As members of the Langham Place Circle, Elizabeth and her new friends helped to promote employment for women, and organised a petition for women's right to vote. In 1859 came Elizabeth's momentous meeting with Dr Elizabeth Blackwell, an English-born woman who had been brought up in America and had managed to qualify there as a doctor. Inspired by her, Elizabeth fought for her own right to enter the profession, and showed extraordinary perseverance and initiative in pursuing her studies. The battle she fought with the University of London, for instance, is on record there: her request to sit for its Matriculation examination was rejected in the Senate only by the single casting vote of the Chancellor in May 1862 (Harte 114). At length she was able to gain her first medical qualification from the Society of Apothecaries in 1865, which would enable to become in 1869 the first woman after Blackwell to have her name entered on the British medical register (Graver 21).

Left: St Mary's Dispensary for Women and Children, at 69 Seymour Place in Marylebone, started by Anderson in July 1866. It would be the first step towards the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital in Euston Road. Source: The Wellcome Library, London. Right: Anderson and Emily Davies in amongst all the male members of the first London School Board. [Click on this for source, and more information.]

By now, she had become a very active promoter of women's rights. In 1865, she and her younger sister Millicent (later Fawcett), together with Emily, Barbara and several other like-minded women, formed a highly influential discussion group called the Kensington Society (amongst the rest were the pioneering headmistresses Dorothea Beale and Francis Buss, John Stuart Mill's wife Helen Taylor, and Anne Clough, sister of the poet Arthur Clough and the first principal of what was to be Newnham College, Cambridge). That was the year in which she set up her first medical practice close to the famous Harley Street area of expensive clinics. The practice thrived, and in 1866 she embarked on a philanthropic project, setting up St Mary's Dispensary for Women and Children in Marylebone. This was the institution that, after moving to the Euston Road in 1890, for many years bore her name.

Elizabeth had garnered a great deal of support for her dispensary, and in 1870 went on to win a landslide victory for a seat on the East London School Board. Women had never been eligible to take part in such an election before, so she was first one in the country to hold this kind of position. Browning himself had been amongst her most energetic campaigners.

Left: The new building for the women's hospital on Euston Road, opened in 1890. [Click on the picture for more information.] Right: Front Surgical Ward, c. 1866 (used for the hospital's jubilee appeal, 1866-1916). Source: The Wellcome Library, London.

The chairman of her campaign was James Anderson of the Orient Steamship Company — her future husband. The couple got married soon afterwards, in 1871. Strong-minded as ever, Elizabeth did not take a vow of obedience at the wedding ceremony, and continued with her pioneering work despite now having her own household to run and children to bring up.* She had recently (in 1870) acquired a medical degree by taking the examination of the medical school at the University of Paris. Now, at her female-staffed hospital, she herself performed operations, even though her first ovarian operation in 1872 had to be carried out in rented premises because of opposition to the procedure. The operation was successful. When the London School of Medicine For Women (later part of the University of London) was established in 1874, through the efforts of Jex-Blake, she became a member of its council and teaching staff, eventually becoming its dean. This was the "first teaching institution specifically intended to train women for degrees" (Harte 128). Elizabeth also found time to write on medical subjects; she prepared a students' textbook as well. That the school was specifically for women reflected something more than the special encouragement required for would-be women doctors in those pioneering days. Like the fact that the staff and patients at her own hospital were female, it recalls "the important part that calls for preserving women's modesty and delicacy played in the Victorian campaign for women to enter the medical profession" (Elston).

After retirement, the Andersons went to live in Aldeburgh, where in 1908 she succeeded her husband as mayor, thus adding another "first" to her list: she was the first ever woman mayor in England. She also continued to support the Suffragist cause, leading a delegation to see Prime Minister Herbert Asquith even in her old age. But she soon left the Women's Social and Political Union, disapproving of their militant tactics.

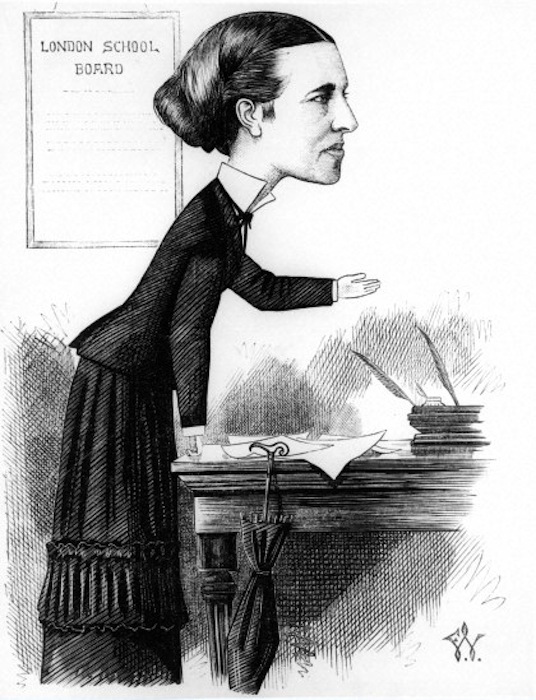

A feisty Anderson, in a caricature initialled by Frederick Waddy. From: Medical Women's Federation, The Graphic, 26 November 1872. Source: The Wellcome Library, London.

This was very much in character: "She was capable, persistent and politically shrewd. She found a way round obstacles instead of charging at them," writes her biographer Jo Manton. Manton also says that Elizabeth "lacked the flamboyance, the oratory, perhaps even the high-level intelligence, of most of the feminist pioneers" (350), but I wonder if she appreciated how dynamic her subject's character really was? As a young woman, Elizabeth Garrett certainly struck the Registrar of the University of London as a "bumptious self-asserting girl" when he first met her. That was in 1860. He guessed that it was the discipline of her studies that subsequently turned her into "a very quiet, lady-like person" (qtd in Harte 128). But perhaps she found that she could achieve more by presenting herself in this way. At any rate, whether by sheer grit, or by a mixture of grit and diplomacy, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson did manage to pursue a high-level career in medicine, and, in so doing, "achieved [the Suffragists'] biggest single breakthrough of the nineteenth century" (Manton 351).

*Like so many Victorian women, Elizabeth suffered the loss of one of her children. One of her two daughters died of meningitis in infancy. Of the surviving son and daughter, it was the daughter Louisa who followed in her mother's footsteps, becoming a surgeon and suffragette herself, co-founding the Women's Hospital Corps during World War I, and publishing a biography of her mother, based on family letters, in 1939.

Related Material

Sources

Clark, Christine. "Garrett, Newson (1812-1893)." The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online edition, accessed 25 January 2008).

Elston, MA. "Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836-1917)". The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online edition, accessed 23 January 2008). [This was my main source of factual information, though there are some discrepancies between this and other sources. For example, did Newson and Louisa Garrett have nine children (as stated by Elston), or "ten surviving" (as stated by Clark)? Elizabeth's husband, too, is variously described as a businessman, merchant and even shipwright....]

Geddes, Jennian. "Anderson, Louisa Garrett (1873–1943), surgeon and suffragette." The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online edition, accessed 13 June 2016).

Graver, Suzanne. "Anderson, Elizabeth Garret (1836-1917)." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia. Ed. Sally Mitchell. New York & London: Garland, 1988.

Harte, Negley. The University of London, 1836-1986. London: The Athlone Press, 1986.

Manton, J. "Elizabeth Garrett Anderson." In Who's Who in Victorian Britain. Ed. Roger Ellis. London: Shepheard-Walwyn, 1997. 349-51.

Last modified 13 June 2016