Preached in St. Paul's Cathedral on Sunday afternoon, the 13th April, being the first Sunday after Easter, 1890, on the text, I John v. 4: "This is the victory that overcometh the world, even our faith." Excerpted (pp.35-38), formatted and illustrated for this website by Jacqueline Banerjee.

epend upon it, brethren, that the true interests of man in this present state of being will really be advanced by his thinking much and very seriously of another. Human life is sweetened, it is braced, by motives which are drawn from a higher world. Simplicity, disinterestedness, care for others, indifference to personal gain or credit, make those who attain to them not only the children of their Father which is in Heaven, but also the salt of the earth, they save it from the moral decomposition which is ever and anon threatening to dissolve the great unwieldy mass of human society. Their toils, their tears, their prayers, arrest the merely selfish impulse of men around them, and they stay the impending judgments of God. Let us be very sure that the world at large owes more than it knows or thinks to those who, living in it, have the least share of its spirit.

There are, in this loud stunning tide

Of human care and crime,

With whom the melodies abide

Of th'everlasting chime;

Who carry music in their heart

Through dusty lane and wrangling mart,

Plying their daily task with busier feet,

Because their secret souls the holy strain repeat.

Assuredly, brethren, we cannot with impunity neglect this, or any other element, of God's revelation of His mind [35/36] and will. For us at this hour the world is just as practical a topic, just as serious an opponent, as it was in the days of the Apostles. It commonly presents itself to us at successive periods of life in different guises. It comes to us in early life as an attraction, I may almost say as a fascination. All the faculties of our minds and bodies are still, fresh and on the alert; it toys with them one after another, addressing itself to the character of each of us with singular adroitness. Here it holds out the prospect of gratifying ambition, and there it discovers large opportunities of pleasure or amusement; and away yonder it veils what is really vicious or degraded beneath the conventional drapery which puts us off our guard, and in doing this it is so skilful and so persistent that we may easily forget what is due to that unseen Friend and Master Whose name we learnt in infancy from our mother, and Who, up till now, has always had a secret place in our heart. All looks so fair that it is difficult even to suspect the precipice that is near at hand, and on the brink of which we may find ourselves without a previous warning. In early life the world stands before us, as the smiling landlord at the door of his hotel meets the traveller, assuring us of a good entertainment and of a hearty welcome, and making no allusion to any less agreeable topic beyond; but in time the pleasantest visit comes to an end, and the bill must be paid.

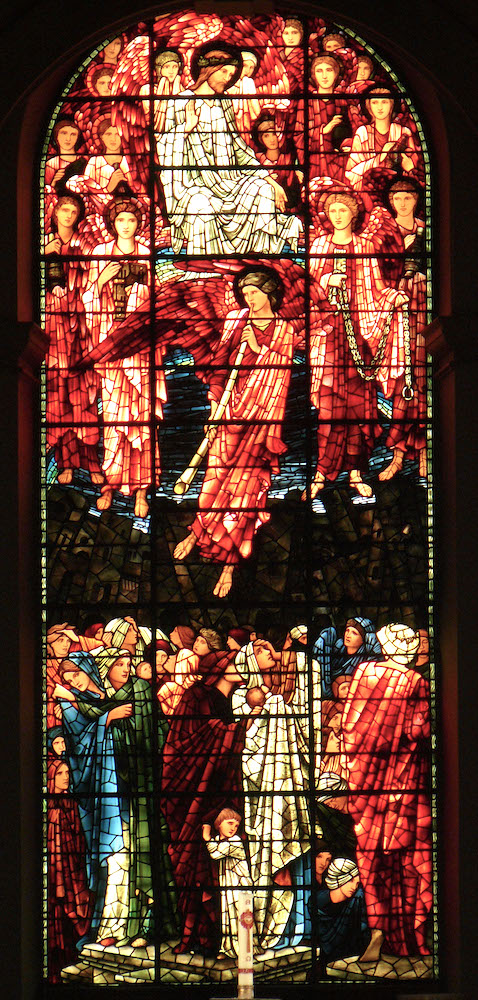

Edward Burne-Jones's The Last Judgement in Birmingham Cathedral (1897).

The Bible is more frank at the outset. "Rejoice," it says, "young man in thy youth, and let thy heart cheer thee in the days of thy youth, and walk in the ways of thy heart and in the sight of thine eyes, but know that for all these things God will bring thee into judgment." And then the world comes to us in middle life less as an attraction than as a tyranny. It brings with it a code of conduct, a body of maxims, which are often opposed to the precepts of the Gospel, but are nevertheless regarded as imperative. To stand on one's own rights, to resent injuries and insults, to make everything give way to getting on in life, to value others not by the real standard of character, but by the superficial standard of wealth or station, to make general acceptableness, and not truth, the rule of our opinions — these are some of its maxims. And it will not be trifled with. When it has once got us in its power, it keeps its eye on us. It reports any symptoms of disaffection, any lapse into high principle, with an implacable regularity; it keeps its votaries well under [36/37] the despotism of ridicule; it sneers down all generous enthusiasm the moment it shows itself; it makes men who desire better things ashamed of their duties, ashamed of their principles; it makes them not seldom insincere and false in their relations with others; it betrays them even into acts of inconsiderateness and of cruelty; it even penetrates into the sanctuary, and it bids the Christian kneeling there consider, not what befits God's presence as the Almighty and the Eternal, not what true and simple devotion would dictate, but what other people are thinking of him, and what will be said of him if he abandon himself to the better guidance of his conscience and his heart. And in later life it often happens that the world no longer attracts or tyrannizes over us from without, not because we have seen through it and bid it begone, but because it has taken possession of us and is now not without but within us. We only do not feel its power as an attractive or an oppressive force because we breathe it as an atmosphere, because, without our knowing it, we are already and altogether controlled by it.

Prayer, by G. F. Watts (1860).

At each of these stages faith is the victory that overcometh the world. As St. John's language implies, to possess real faith is to be already victorious. Faith matches the world's attractiveness in early life because it can offer a real, and much more powerful, attraction. There is more to fascinate the human soul in the eternal beauty than in any form or ideal of earthly mould, more to interest the mind and the affections in the contemplation of the love of God than in any earthly occupation, however pleasurable or engrossing. And faith overthrows the worldly spirit in middle life. It achieves this by opening and fixing the eye of the soul upon the one Being Who has a right to rule it because He is what He is, holy, just and good. As we see Him more clearly the world loses its power; its most cherished maxims are placed in the light of His countenance, and we see how little they can really do for the improvement and happiness either of ourselves or others.

And, once more, faith is equal to the hardest task of all, — that of expelling the worldly spirit when, like a London fog, it has penetrated into all the recesses of our spiritual home; for faith takes us by the hand, points us to a height from which, as from the outside gallery of this church above our heads on some winter day, it can look down upon the [37/38] mists in which life is buried below, and determine that it shall no longer be so. To see our Lord, the Sun of Righteousness, as He is seen by a Christian's faith is to have taken the world's measure, is to have parted company with it here and for ever.

Links to Related Material

- Henry Parry Liddon, D.D., D.C.L., Chancellor and Canon of St. Paul's

- Christian Philanthropy (excerpt from another sermon at St Paul's)

Bibliography

Canon Liddon: A Memoir..... London: Office of The Family Churchman, 1890: 5-12, in the Internet Archive, from a copy in Harvard University Library. Web. 4 November 2023.

Created 4 November 2023