This review is reproduced here by kind permission of the online inter-disciplinary journal Cercles, where it was first published. The original text has been reformatted and illustrated for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee, who has also added links. Click on the images for larger pictures and bibliographic information.

Thanks to the collaboration between the Freer Gallery in Washington, the Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, Massachusetts, and the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London, a travelling exhibition devoted to James McNeill Whistler's depictions of the river Thames will be presented between October 2013 and August 2014. Of course, due to specific restrictions (though it owns the largest collection of Whistlers in the United States, if not the world, the Freer cannot lend any of its works) or to sheer lack of space (the rooms devoted to exhibitions in Dulwich are extremely small), the three versions of this show will be as different as can be. The rather obscure Addison Gallery was probably included in the circuit because it hosts the very first oil painting inspired to Whistler by the Thames, Brown and Silver: Old Battersea Bridge (RA 1865). The Dulwich Picture Gallery owns nothing by Whistler, but it must have seemed logical to have a venue in London for an exhibition about the most English of American painters.

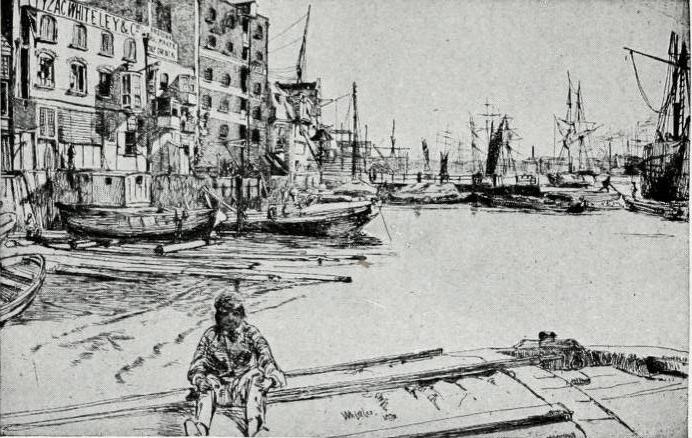

The catalogue includes no less than 79 works by Whistler, culminating with the splendid Nocturne: Blue and Gold — Old Battersea Bridge (Grosvenor 1877), plus some twenty Japanese prints and Victorian photographs. The exhibits are divided into several categories: "Etching and Drypoint," "The Thames set," "The Oil Paintings: Whistler's 'Daylights,'" "Chelsea," "Lithographs and Lithotints: from Limehouse to Old Battersea Bridge," "Nocturnes," "Old Battersea Bridge," "Japonisme," "Photographs," which allows to cover all the aspects of the artist's production in relation with the Thames, including the decorative arts, with sketches for plate designs or wall frescoes (unfortunately, the University of Glasgow did not lend the extraordinary Blue and Silver: Screen, Old Battersea Bridge, a folding screen which Whistler kept in his own house, and in front of which he was photographed). This is an impressive array of Whistlerian works, and it is quite a treat to find them gathered within the covers of one single book.

Two etchings from the Thames Set, which Whistler commenced in 1859. Left: Eagle Wharf. Right: Putney Bridge.

Two essays and a short biography precede the catalogue proper, and those texts are of such a nature that they could well be found fault with by many an admirer of Whistler's work. Perversely enough, in their examination of one of the foremost exponents of Art for Art's Sake, Margaret F. Macdonald, curator of the Whistler, Women, and Fashion exhibition at the Frick in 2003, and Patricia de Montfort, also of the University of Glasgow, have decided to reverse the usual emphasis, by focusing on some aspects which may seem rather irrelevant. They insist on the socio-historical value of Whistler's art, as if one's attention should turn to his paintings in order to know what the Thames looked like in the 1850s. "But there is also a strong sensitivity to subtle colours and complex textures, and to the qualities of the medium, be it lithography, etching or oil paint, that is reflected in his treatment of each subject" (11): with such a concession, the authors almost reluctantly grant the aesthetic quality of Whistlerian works. This approach may function with the painter's early production; Whistler's own mother considered that the subject of a canvas like Wapping (RA 1864) was "The Thames & so much of its life, shipping, buildings, steamers, coal heavers, passengers going ashore, all so true to the peculiar tone of London & its river scenes" (19), and his first view of Battersea Bridge was celebrated by Victorian critics for its truth of tone and its fifty shades of grey. Nevertheless, in England, Whistler went through a conversion which took him from Courbet-like realism to Albert Moore's Aestheticism, he soon came to be perceived as a slovenly kind of Pre-Raphaelite (according to Tom Taylor in 1865, [23]), "abandoning topographical detail entirely" (32), and the musical aspect of his work became crucial: his patron Frederick Leyland suggested the French word Nocturne as a title for his night views of London, and all his early works were later re-christened through the addition of their dominant colours, Old Battersea Bridge thus becoming Brown and Silver: Old Battersea Bridge for the 1892 retrospective exhibition.

Patricia de Montfort is especially guilty of that paradoxical appreciation of the artist, which can lead to very curious assertions. "Certainly, the evolution of Whistler's pictorial narrative in many of his Thames images between 1859 and 1874 seems to correlate with a more universal public narrative to 'tame' the riverside and to promote social order and commercial prosperity" (32). The coincidence of two events does not mean that there is a direct link between them. Besides, one might suggest that "Certainly" and "seems" are strange bedfellows, but this is still nothing if compared with some other contestable formulas: "Casting a gaze over the Thames from the upper-floor window of Lindsey Row in the late 1870s, Whistler may well have wondered at the effect of its growing number of bridges upon a vast, fragmented city," "Whistler may also have noticed changes in the spatial relationship between river and bridges" (47; emphasis added). Did the artist really care for the role of bridges as "crucial links in a network of routes for commuting city workers and incoming horse cart traffic, laden with consumer goods" (41)? If he did, he certainly did not show it in his work, and it does take some imagination to actually see "ruddy-faced boatmen" (49) even on his earliest canvases. More interesting is the development about "Whistler's own economic relationship with his bridge subjects," but here again, the conclusion is absurdly based on a pure coincidence of events: "As Battersea Bridge aged and grew more decrepit in the 1880s and its value as a crossing diminished, the value of Whistler's aestheticised visions of it began to rise" (41-42).

Finally, one might also have expected a wider view of Whistler's possible influence on the artistic perception of London: it was a good idea to look at the photographs taken by James Hedderly (1815-1885) in the 1860s, which documented the neighbourhood of Battersea Bridge, but it might also have been fruitful to look at the pictorialist images created round 1905 by Alvin Langdon Coburn, another American in London. The paintings of another exile, James Tissot, might also have given food for thought, since the Frenchman produced many works inspired by the Thames in the 1870s, with backgrounds as packed with masts and sails as Whistler's Wapping, or with views of the Gravesend docks which do recall Whistler's Thames Set of etchings.

References

McDonald, Margaret F., and Patricia de Montfort. An American in London: Whistler and the Thames. London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 2013. Hardback, 192 pp. ISBN 978-1781300060. £35.00.

Last modified 19 January 2014