Two details from Cleopatra (1872) by Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Click on thumbnail for larger image.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema completed his portrait of Cleopatra in 1877, a time when he was already established in England and gaining increasing popularity as a painter of Roman classical scenes. The ornamental frame with Egyptian style embroidery that the work appears in now was introduced after the artist was knighted in 1899 and so it is worth considering the impact of the painting independently of the frame which was introduced two decades after its completion. Like many of his paintings, Cleopatra is delightfully ambiguous and minimal in composition, especially when compared to other artists' attempts at the same subject.On one hand the viewer is given access to the empress's boudoir as she reclines and relaxes. The light tone of her flesh stands out from the dark and mostly brown hues of the rest of the painting. Yet the painting is by no means voyeuristic or erotically charged. Equally, Cleopatra is not blatantly identified as a queen since one can hardly notice the subtle crown on her head. So on the surface the painting seems to be quite plain, the woman quite ordinary inspite of her posture and clothing. However, on closer viewing, Cleopatra's gaze becomes quite captivating. It is striking that although the empress should be looking away from the viewer, as she is being viewed from the side, she seems to be slyly watching the viewer, acknowledging and participating in his or her gazing at her, indeed returning a disguised glance of her own. We are not struck, then, by her beauty or her costume, neither of which are aesthetically emphasized, but rather by the seductive ambiguity of Cleopatra's gaze which gives her a subtle but nonetheless alluring charm. As many recent historians have debunked the romantic legends surrounding her image, this painting seems to be an apt celebration of the woman as ordinary to look at but seductive nonetheless.

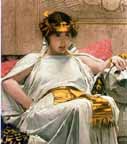

Cleopatra by J. W. Waterhouse. Click on thumbnail for larger image.

John William Waterhouse's 1888 painting Cleopatra takes an entirely different route of expression, no doubt influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite movement which was in vogue during the latter half of the nineteenth century. His seated Cleopatra relishes her power as she affects a magisterial pose, lowering her eyes at the viewer and pointing her crown out aggressively. Waterhouse opts to play upon the myth of Cleopatra, portraying her as a gender-defying femme fatale charged with a castrating power that would vie with any of Dante Rossetti's 'stunners'. The woman's bright red lips foreground her robust sexuality and act as a metonym for her covered genitalia. By clothing herself completely, only allowing the viewer small glimpses of her arms and neck Cleopatra exploits male scoptophilic desire and anxiety by making herself sexually attractive but unavailable at the same time (a hallmark of the Pre-Raphaelite woman).

As we have seen, both artists approach the subject of Cleopatra from entirely different angles. Of course Waterhouse's version is visually much more exciting, but rather importantly it reminds us that the classicist revival in British art was based upon the supposedly Roman values of decorum and restraint where rationality was meant to be the controlling force, giving everything a subtle order. Naturally there was always a gap between these ideals and the reality of Roman life, and this gap allows Alma-Tadema to make interesting use of ambiguity and give us a subtle window into Roman history.

Questions

1.Which painting is more appealing to a modern audience or is it a matter of taste?

2. Does Alma-Tadema's version benefit at all from being so ordinary on the surface?

3. Do both paintings reflect changing values towards woman during the period?

4. Was historical realism one of Alma-Tadema's aims or indeed a classicist aim?

5. How does the framing (the visual space) affect each painting?

6. Does Alma-Tadema challenge the contemporary beliefs about his subject?

Bibliography

Barrow, R. J. Lawrence Alma-Tadema. London: Phaidon, 2001.

Last modified 8 February 2007