Henrietta Rae, the first woman to exhibit nude paintings at the Royal Academy, was born 30 December 1859, at Hammersmith, and died in Upper Norwood, London, 26 January 1928. As a child, Rae studied at the Queen Square School of Art (which became the Royal Female School of Art). According to her biographer, Arthur Fish,

Art training in those days was a most serious and depressing business, especially to a young, vivacious pupil. A rigorously enjoined course of freehand drawing (so-called) was in itself sufficient to cure an ordinary craving for the artistic life, and the irresponsible spirit of Henrietta Rae rebelled against its deadly dull routine. [19]

In 1874, Rae’s rebellious spirit, says Fish, led her to “join the ranks of the free-lances who studied art in the Antique Galleries of the British Museum” (Fish 20-21), and here she met her future husband, Ernest Normand. She enrolled for evening classes at Heatherley’s School of Art in Newman Street—where she was the first female student—and began applying to be a probationer at the Royal Academy Schools. Fish notes that it was not until 1877, “after five unsuccessful attempts,” that Rae was finally admitted (Fish 24).

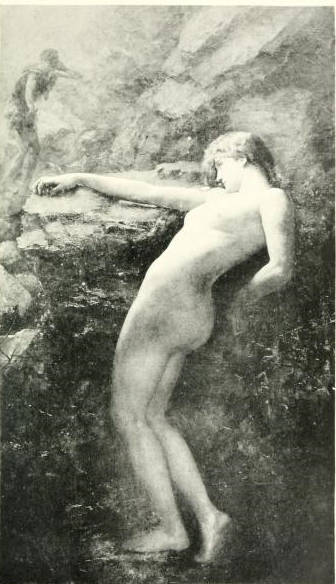

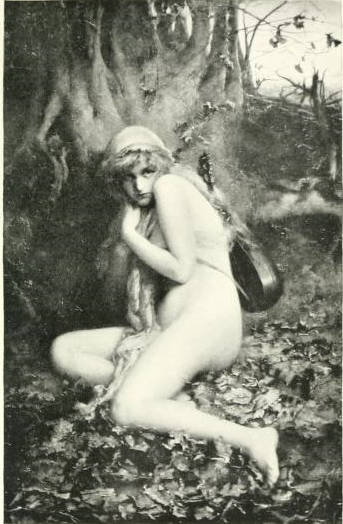

While still a student, Rae began exhibiting in 1879. Her first exhibited work was a landscape, Sketch Near Lee), at the Spring exhibition of the Royal Society of Artists. That winter, she exhibited a portrait study of herself in Empire costume, titled La fille de l’Ancienne Noblesse), at the Dudley Gallery. By 1881, she had begun exhibiting at the Royal Academy: a portrait of Miss Warman). In 1884, she married Ernest Normand and continued to work as an artist under her own name, exhibiting two nudes, A Bacchante) and Ariadne Deserted by Theseus) at the Royal Academy in 1885. In 1887, she exhibited Eurydice Sinking Back to Hades), and in 1888, Zephyrus Wooing Flora).

A Bacchante. 1885. Eurydice Sinking Back to Hades. Click on images to enlarge them.

These three paintings exemplify the primacy of classical subjects for nude art in the nineteenth century. Most of the figures are demurely draped at strategic points of the body, and all are pale and luminous. Yet, these figures also embody a kind of awkward vitality. Oddly enough, the calm and sturdy Bacchante looks reasonably relaxed, but both Eurydice and Flora appear to be straining for something or someone. Eurydice is reaching towards Orpheus as she sinks back to Hades, and Flora is reaching upward to Zephyrus, the god of the West Wind and lover of the beautiful youth Hyacinthus. All three female figures evince a kind of authenticity by appearing to be, not idealized classical statues, but genuine Victorian models who are consciously playing the role of mythological beings.

Left: Hylas and the Nymphs. Right: Psyche Before the Throne of Venus. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

A similar self-reflexive humanness can be seen in later nudes by Rae, including Psyche Before the Throne of Venus (1894) and Hylas and the Water Nymphs (c. 1909).

Both these paintings depict large, somewhat theatrical tableaux, in which the figures appear to have been posed and yet remain relaxed, giving each scene a paradoxically contemporary sense and almost parodying the late Victorian exaltation of classical mythology as a subject for fine art.

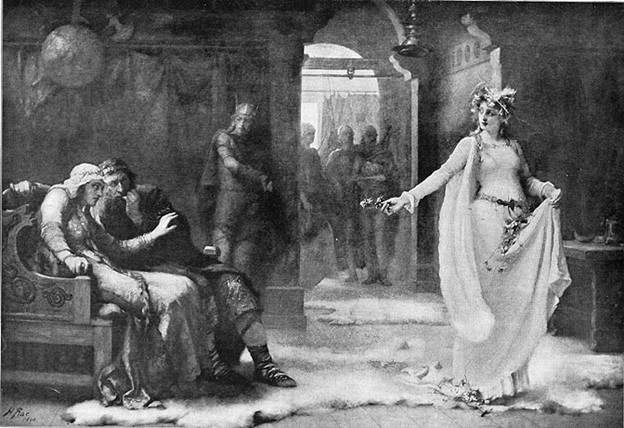

Ophelia. 1890. Walker Art Gallery.

Rae also produced narrative pictures based on literature, for example, depicting one of the most popular literary figures in Victorian painting, Ophelia. Fish remarks on Rae’s departure from the usual composition of a picture of Ophelia alone, showing her instead with other characters in the play: “a beautiful figure, with the strained, intense look of insanity in her eyes as she glances at the occupants of the room” (Fish 57). He also records the fact that while Rae was painting this picture, she evidently received perhaps too much fatherly advice from her distinguished neighbour and mentor, Frederic Leighton.

When the painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1890, Rae and Normand were disappointed and hurt because it and Normand’s entry for the exhibition, Vashti Deposed, were both hung badly: above the line in one of the smaller rooms, on either side of a doorway. Even though the paintings sold, Normand and Rae took the poor hanging as a sign of disapproval from the Academy and decided to go to Paris and study at the Atelier Julian.

La Cigale. 1891.

During July 1890, Rae and Normand spent time at an artist (mainly impressionists and international) colony in the village of Grez, near Fontainebleau. Upon their return to London, Rae showed the deep influence of this experience in La Cigale (‘The Grasshopper,’ alluding to the fable of the Grasshopper and the Ant), which was splendidly hung, on the line, at the Royal Academy Exhibition of 1891. Leighton criticised the figure in this painting for lacking “edge,” but John Everett Millais warmly praised it, reportedly saying, “I would give my left hand to be able to paint flesh like that” (Fish 74-75).

That same year, 1891, Rae painted one of her most popular works, an idealized portrait of Florence Nightingale at Scutari, titled The Lady of the Lamp. Rae’s Nightingale has a saintly, statuesque aspect, in contrast with the timid expression of La Cigale—perhaps unsurprisingly, given the thematic differences between the two paintings. Although Nightingale is made into a nationalistic icon here, as in other depictions of her, she is neither allegorical nor mythological, but solidly real. She is swathed in many folds of drapery in the form of a large white scarf, almost a veil, and a dark skirt, and gazes in a serious and detached manner down at the grateful soldier who looks up at her in awe. The positioning and treatment of The Lady and La Cigale could hardly vary more. At the same time, the strength of Rae’s Lady owes a great deal to the many nudes Rae painted before this work, and she shares with them a solidity and a warm, tangible physical and emotional presence. The Lady of the Lamp appeared as a chromolithograph for Cassell’s Christmas annual, Yule-Tide.

Left: The Lady of the Lamp. 1891. Right: Sir Richard Whittington dispensing his Charities. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In 1892, Rae exhibited Mariana, based on Tennyson’s poem, at the Royal Academy. She also began her large (ten feet by six feet four inches) canvas, Psyche Before the Throne of Venus, which was completed and exhibited in 1894. Rae began work on the painting while she and Normand were living in Holland Park, and she was able to use William Richmond’s studio. She completed it in 1894 at her new studio in Upper Norwood. With this painting, as Fish notes, Rae returned to classical subjects (Fish 80). She also drew on William Morris’s Earthly Paradise:

But even then the flame of fervent love

In Psyche's tortured heart began to move,

And gave her utterance, and she said, "Alas!

Surely the end of life has come to pass

For me, who have been bride of very Love,

Yet love still bides in me, O Seed of Jove,

For such I know thee; slay me, nought is lost!

For had I had the will to count the cost

And buy my love with all this misery,

Thus and no otherwise the thing should be.

Would I were dead, my wretched beauty gone,

No trouble now to thee or any one!"

And with that last word did she hang her head,

As one who hears not, whatsoe’er is said;

But Venus rising with a dreadful cry

Said, "O thou fool, I will not let thee die!

But thou shalt reap the harvest thou hast sown

And many a day thy wretched lot bemoan.

Thou art my slave, and not a day shall be

But I will find some fitting task for thee,

Nor will I slay thee till thou hop’st again.” (p. 408)

Leighton approved of this painting, though he qualified his approval by complaining about its “tendency to prettiness.” The picture was given a central place at the Royal Academy Exhibition, where it drew the attention of M.H. Spielmann, who called it “remarkable in its conception and execution” (Fish 81). After praising the delicacy of the tones, Spielmann offered this critique: “But we instinctively feel that the painter has never quite grasped the greatness of this scene of classical mythology—the figures, with all their charm, are not inhabitants of Olympos [sic], but denizens of an ungodly earth” (quoted in Fish 83). I would suggest that this sense of earthly humans rather than remote gods is characteristic of Rae’s paintings and a strength rather than a weakness. The theatricality of the scene, like that of Hylas and the Water Nymphs, can be read as a deliberate representation of the play-acting involved in Victorian neo-classical art.

Rae’s later work at the turn of the century included her large mural, Sir Richard Whittington dispensing his Charities , painted for the Royal Exchange in 1900. This work spanned eighteen by twelve feet, and Rae and Normand—who was commissioned to paint the panel on King John Granting Magna Carta,—had two pits sunk in their studio so that they could each work on these enormous canvases. There were to be 24 panels painted by different artists, and funding came mainly from various city guilds. The completed wall panels include Frederic Leighton’s Phoenicians Bartering with Ancient Britons, The Crown offered to Richard III at Baynard's Castle, by Sigismund Christian Hubert Goetze, and Modern Commerce, by Sir Frank Brangwyn.

Rae continued to paint portraits, including one of the Marquess of Dufferin, commissioned by the Belfast Yacht Club (of which he was the commodore) in 1899 and exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1900. Lord Dufferin suggested to her the subject of Sirens, which was hung on the centre of the line at the Royal Academy in 1903.

The Sirens. 1903.

Pamela Gerrish Nunn notes that Rae was awarded honourable mention at the Paris Exposition of 1889 and a medal at the Chicago world fair of 1893 (Oxford DNB). Rae was the first woman to serve on the hanging committee for the fall exhibition at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, in 1893; in 1897, she was president of the women’s section at the Victorian Exhibition, Earl’s Court. She continued to exhibit at the Royal Academy until 1919. Henrietta Rae died 26 January 1928 at her home in Upper Norwood.

Bibliography

Fish, Arthur. Henrietta Rae (Mrs. Ernest Normand) . London: Cassell and Company, 1905.

Gentle Author. Save the Royal Exchange Murals!Spitalfields Life. August 25, 2016. Web. 3 July 2020.

Herrington, Katie J.T. and Rosie Jarvie. . Henrietta Rae (1859-1928) Psyche before the throne of Venus. London: Martin Biesly Fine Art, 2018. Web. 3 July 2020.

Morris, William. The Earthly Paradise: A Poem. London: F.S. Ellis, 1868.

Nunn, Pamela Gerrish. “Rae [married name Normand], Henrietta Emma Ratcliffe (1856–1928).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Web. 26 June 2020.

Last modified 3 July 2020