The Fine Art Society, London, has most generously given its permission to include Lynn Thornton's introduction to Eastern Encounters, the catalogue of a 1978 exhibition, in the Victorian Web. The copyright remains, of course, with the Fine Art Society. The images, which are not in the original essay, have been added from those in the Victorian Web. — George P. Landow

Introduction

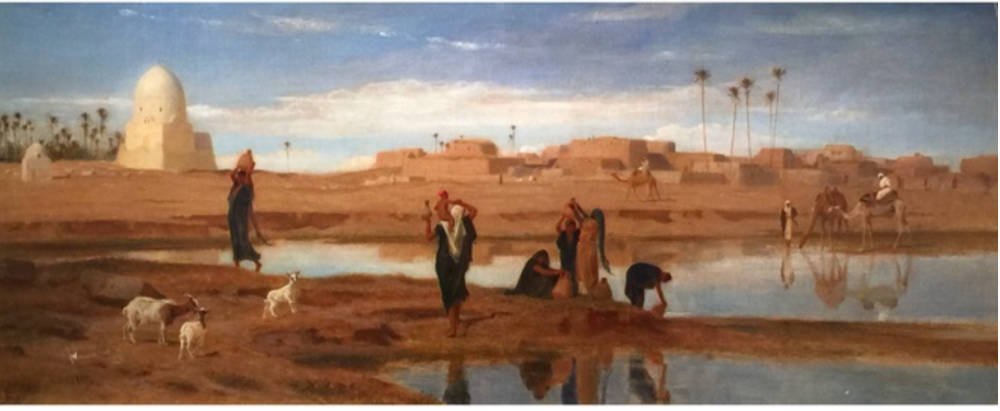

On the Banks of the Nile by Frederick Goodall. Click on images to enlarge them.

n the nineteenth century the

countries around the

Mediterranean basin attracted

an increasing number of

Europeans, exploring,

exploiting, sketching,

photographing, noting

impressions in pen and pencil,

or just visiting. The West was

finally beginning to

understand a little of the

Orient; it no longer seemed

like a mysterious, elusive

mirage. The Orient, however,

was changed by this contact,

as delicate rose petals bruise

when clumsily touched.

Indeed, much of it has now

sadly been ravaged by the

encroachments of occidental

civilisation, war and

revolution. The pictures in

this exhibition are often,

therefore, invaluable records

of a way of life which was,

even then, fast disappearing.

n the nineteenth century the

countries around the

Mediterranean basin attracted

an increasing number of

Europeans, exploring,

exploiting, sketching,

photographing, noting

impressions in pen and pencil,

or just visiting. The West was

finally beginning to

understand a little of the

Orient; it no longer seemed

like a mysterious, elusive

mirage. The Orient, however,

was changed by this contact,

as delicate rose petals bruise

when clumsily touched.

Indeed, much of it has now

sadly been ravaged by the

encroachments of occidental

civilisation, war and

revolution. The pictures in

this exhibition are often,

therefore, invaluable records

of a way of life which was,

even then, fast disappearing.

The taste for exoticism in painting goes back a long way before the Orientalists became fashionable in the nineteenth century. European artists, however, mostly painted stereotyped images of turbanned inhabitants of miraculous far-off lands, set against Western backgrounds. The eighteenth century brought a new interest in the Near and Middle East, but the artists, mainly topographical or amateur, were concerned only with classical antiquity and they had little eye for the contemporary life in Islamic countries. It was not until the early nineteenth century that the West truly encountered the East. The writings of the Romantics, enamoured of the Orient, rapid colonial expansion, strengthened diplomatic and commercial links which made travel easier in hitherto hostile countries, and the emergence of Arabist scholars, gave an unprecedented impulse to writers and painters. They went in search of the unknown, to escape from the greyness of industrialized cities into lands of light and colour, and to record the customs, clothing and architecture. Some of these Orientalist painters spent many years in the East, either travelling with the nomads or living in the more westernized cities, Constantinople, Cairo, Alexandria. Others were official painters with military or scientific expeditions. Many went abroad for a few months but continued to base their paintings destined for the Royal Academy or the Salon on sketches drawn on the spot, studio accessories and photographs. A few painted the Orient without ever having put a foot outside their home country!

The French Orientalist painters were so numerous that they can be classified as a School, although each generation had its own vision of the East. The popularity of Decamp's paintings of Asia Minor, the French conquest of North Africa, which brought commissions to military and topographical artists, Delacroix's revelation of vibrant colour in Morocco, Marilhat's majestic landscapes, Dohedencq's crowd scenes and Chasseriau's portrayal of the fatalistic Arab, launched the success of the Orientalists at the annual Salon des Artistes Français. The Masters inspired innumerable minor artists who painted ad nauseum mosques, caravans, harems and bazaars. By 1869, Theophile Gautier, one of the most perspicacious and influential critics, was writing: "the caravan continues its route. One only hopes that it does not leave too many corpses of camels on its way." The French public in the '70s was certainly beginning to tire of Orientalism but the genre was, however, given a new lease of life by Fromentin and Guillaumet who, appreciating the innovations of impressionism painted sensitive understated pictures of desert and rural life.

In the latter half of the century, the Orientalists were divided into several camps:

- the "North Africans," who painted people and landscapes in a naturalistic way;

- the artists who revelled in fantasy scenes of violence, sensual bejewelled odalisques, fierce tribesmen and chained prisoners;

- the artists like Gerome and his school who studied Oriental figures and architecture with painstaking, minute exactitude.

Those genre pictures were particularly appreciated by an emergent American society for "their brilliancy, their manifest skill, their deceptive imitation of textiles, their amusing modern anecdotes or reconstructions of old fashions and costumes. The new pictures naturally went into new houses with the new furniture and the new clothing" (Isham).

The Orientalists continued to exhibit at the Artistes Francais, at the Salon National des Beaux-Arts, formed in 1890, and, from 1893, at their own annual Salon des Peintres Orientalistes Francais. But the public, for whom everything eastern had once been strange and unknown, had, by the 1890s, become accustomed to seeing reconstructions of mosques, Arab villages and bazaars at Universal Exhibitions. Even the Oriental nude lost something of her savour, as soldiers sent postcards of the local beauties from all parts of the French Empire.

The Orientalists were, however, able to adapt to changing tastes, and developed a more modern style. A North African school was formed around the Villa Abd-el-Tifin Algiers, the Villa Medecis of the Orient, while Black Africa and Indo-China provided new motifs for the colonial painters of the twentieth century.

Orientalism in Britain was more individualistic than in France. It was also less prolific, although Britain in the nineteenth century was at the height of her maritime power and was the greatest industrial and trading nation on earth. Her interest in the Orient was aroused for many reasons: the development of travel to India, her political and commercial involvement in the Middle East, the widespread success of the Illustrated London News and scientific publications, and the revival of religious fervour, which sent scholars and divines to the Holy Land.

India, Asia-Minor, Palestine, and Egypt and her dependant countries, Syria and the Lebanon, were the favourite haunts of British artists. Persia was more or less closed except to diplomatic missions, Arabia was relatively uncharted and dangerous, and even expeditions to Sinai and Petra were not to be lightly undertaken. These lands were visited by excellent topographical artists, many of whom had been trained as architectural draughtsmen.

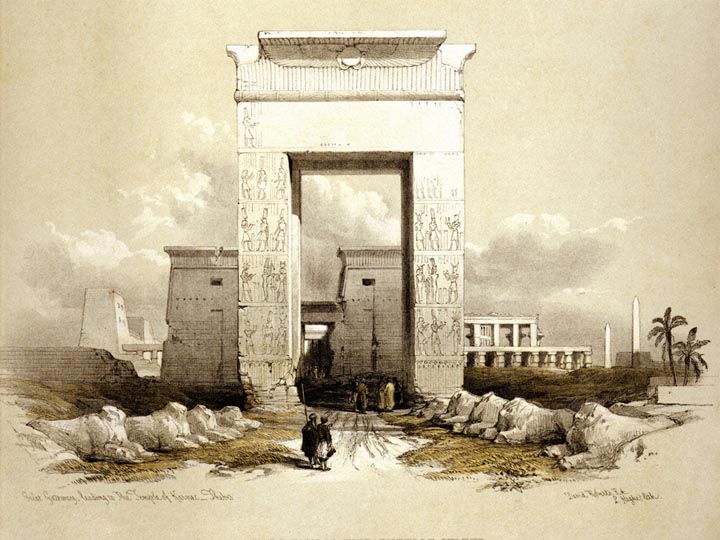

Left: Great Gateway leading to the Temple of Karnac, Thebes by David Roberts, R.A. Right: Eygptian No. 1 by Owen Jones from The Grammar of Ornament.

The most notable were Roberts, Bartlett, Allom, Purser, Page, Bonnomi, Owen Jones, whose work was engraved and published in heavy ornamental tomes. The advent of photography, however, severely curtailed their activities when photographers like Francis Frith brought back accurate records of the sites, which familiarized the public with hitherto little-known countries.

Three of Frith’s photographs from Egypt and Palestine (1858-59): Left: The Great Pylon at Edfou. Middle: The Sphinx and Great Pyramid, Geezeh. Right: The Statues of Memnon, Plain of Thebes.

The camera was, however, never a serious threat to such painters as Edward Lear, whose landscapes in a free open style could never be imitated by a photographer.

Many Victorian artists were interested in the East only in so much as it provided them with backgrounds for their religious paintings; even Frederick Goodall, whose Egyptian fellahs, camels and oases are in the pure Orientalist tradition, admitted that he visited Egypt only in order to study Scriptural subjects. There were, however, a few artists who were far more interested in contemporary Islamic life than the classical or Biblical past. Although their paintings attracted a good deal of attention, particularly the oils and watercolours of J. F. Lewis, the public also enjoyed fantasy scenes of luscious slave girls seen at the Academy. Not only the public, but the artists sought escapism; both in England and France they filled their studios with textiles, arms and objects. Chasseriau, for instance, had

yatagans, kanjars, Persian daggers, Circassian pistols, Arab guns, old Damascus blades encrusted with verses from the Koran, arms enriched with silver and coral, all this delightful display of barbaric luxury grouped like trophies along the walls; casually hanging were gandouras, haiks, bournus, caftans, giving the eyes a feast of colour by which the artists attempt to forget the dismal and the drab; for they seem to have captured the sunrays of Africa in their crumpled and gleaming folds.' (Gautier).

This tremendous enjoyment of brilliant colour and the study of the effect of bright sunlight was one of the most important contributions of the Orientalists to pre-Impressionist painting. Ruskin felt that "it is wholly impossible to paint an effect of sunlight truly. It has never been done, and never will be. Sunshine is brighter than any mortal can paint, and all resemblances to it must be obtained by sacrifice." Thomas Seddon noted that the sunlight in Cairo made the palm trees look grey, while J. F. Lewis "used to try experiments by putting coloured pieces of drapery in the courtyard of his residence to see the effect of sun on them . . . the vivid light robbed the colours upon which it immediately fell and rendered all a sort of white." Eugene Fromentin went further in his analysis:

The shadow in this land of light is inexpressible, it is something dark and yet at the same time something transparent and coloured - like deep waters; they look dark, but as soon as the eye has penetrated them, one is quite astonished to discover that there is luminosity in them! One has only to think the sun away and this shadow is itself transformed into light.

1. Turkey

ontact between Turkey and

the West goes back for many

centuries. The Levant

Company was founded, with

Elizabeth I's encouragement,

in 1581, while commercial

agreements between Italy and

Turkey were consolidated

after the conquest of

Constantinople in 1453.

Trading houses were set up

on the Golden Horn, while

Turkish, Greek and Arab

merchants and craftsmen had

their own districts in Venice

itself. Despite this, the myth

of the cruelty and savagery of

the Saracen was maintained

in a Europe who feared

possible invasion. By the late

seventeenth and early eighteenth century,

however, European diplomats,

architects and travellers had

settled in Constantinople, so

that there was a liberal

cultural exchange. The artist

Vouet was followed by Carrey,

Liotard, de Favray, Melling

and Vanmour, who were

much appreciated by the

Turkish Court. Conversely,

turkeries became as

fashionable in eighteenth century

France as chinoiseries;

artists who had never been to

the Levant painted portraits

of turbanned Parisians

en sultane.

ontact between Turkey and

the West goes back for many

centuries. The Levant

Company was founded, with

Elizabeth I's encouragement,

in 1581, while commercial

agreements between Italy and

Turkey were consolidated

after the conquest of

Constantinople in 1453.

Trading houses were set up

on the Golden Horn, while

Turkish, Greek and Arab

merchants and craftsmen had

their own districts in Venice

itself. Despite this, the myth

of the cruelty and savagery of

the Saracen was maintained

in a Europe who feared

possible invasion. By the late

seventeenth and early eighteenth century,

however, European diplomats,

architects and travellers had

settled in Constantinople, so

that there was a liberal

cultural exchange. The artist

Vouet was followed by Carrey,

Liotard, de Favray, Melling

and Vanmour, who were

much appreciated by the

Turkish Court. Conversely,

turkeries became as

fashionable in eighteenth century

France as chinoiseries;

artists who had never been to

the Levant painted portraits

of turbanned Parisians

en sultane.

The last days of the glory of the great Ottoman Empire were recorded by Hilaire, Preaulx, Page, Dupre and Mayer, who visited Turkey before the first reforms, the law passed by Mahmud II obliging the Turks to abandon their traditional costumes, and the elimination of the powerful Janisseries in 1826.

With the popularity of Alexandre Decamp's genre paintings, so admired by Gautier and the Marquis of Hertford, Asia-minor took on different colours in the 1830s and 1840s. In heavy impasto, with ivory light and black shadow, in the manner of the Dutch Masters, they set the style for Orientalist pictures for many years. Inspired by the heroism of Missolonghi during the Greek War of Independance, Byron, Hugo, Delacroix, became partisans of freedom, and through their genius, the Turk became once again the image of the bloody despot. But by the Crimean war in 1854, Europeans had gone back to a more realistic view. Constantinople was invaded by English and French soldiers, sight-seers wishing to visit the Front, correspondents for the Illustrated London News, The Times and L' Illustration, and accredited artist-reporters such as Constantin Guys and William Simpson.

Gone were the days of mysteriously veiled women riding in ox-drawn arabas or chattering by the Sweet Waters of Asia, painted by Laurens, Preziosi, von Chlebowski, Pasini, Lewis, Berchere and Brest; gone were the props of this theatrically rococo city described by Chateaubriand, de Nerval, Gautier, de Lamartine. The sultanas were dressed by Worth and steamships and factories lined the Bosphorus. Even Ziem, one of the best known painters of the Golden Horn, beat a retreat saying "The Orient is Venice."

The Turks formed their own school in the late 19th century, led by Osman Hamdy Bey, a pupil of Gerome, and Zonaro. But the last gleams of past exoticism was to be found in the shimmering blue and pink pastels of Lucien Levy-Dhurmer, inspired by the writings of Pierre Loti -- evocative, nostalgic, they spoke of ephemerality, death, disenchantment and irremediable solitude.

2. Egypt

n 1517, Egypt, formerly

under the rule of the

Omayyades and the

Mamluks, had become a

pachalik of the vast Ottoman

Empire. After Napoleon's

invasion of Egypt in 1798,

which heralded an era of

European patronage in the

East, a new dynasty was

founded in 1805 by Mehemet

Ali.

n 1517, Egypt, formerly

under the rule of the

Omayyades and the

Mamluks, had become a

pachalik of the vast Ottoman

Empire. After Napoleon's

invasion of Egypt in 1798,

which heralded an era of

European patronage in the

East, a new dynasty was

founded in 1805 by Mehemet

Ali.

There was a flourishing Levantine community in Alexandria, and the presence of Greeks, Maltese, Syrians and Jews bridged the gap between East and West. In Cairo, Europeans lived in the Esbeikah area, and although newly-arrived visitors shuddered at the noise and squalor, the residents had most of the pleasure and little of the pain of living in an Oriental city. The artists of the 1830s and 1840s, Lewis, Gleyre, Marilhat, Muller, Roberts, and the sociologist of modern Egypt, Edward William Lane, found it still thoroughly Eastern . . . "turbanned Turks in rich pelisses, Arabs in the graceful bournus, Copts in fringed garments of camel's hair and half-naked Nubians, their black limbs relieved by some scanty drapery of white cotton" (Muller). But by 1854, Thomas Seddon was writing: "this country is a spectacle of a society falling into ruins, and the manners of the East are rapidly emerging into the encroaching sea of European civilisation." The Khedive Ishmail, to welcome European dignitaries for the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, gave Cairo a face lift. Swamps were drained, hotels built, the Opera opened -- with Verdi's Aida -- and transport between Alexandria and Cairo improved. Thomas Cook began to organise his trips up the Nile and into the Holy Land, the meticulously planned tours protecting its members as far as possible from the rigours and discomforts of contact with the country. By the 1890s, Cook's were managing to house a thousand visitors under canvas at one time. "The Nile is now being visited by crowds almost equal in number to those of the multitude which flocks to the Riviera," wrote Somers Clarke. "Egypt is indeed becoming a fashionable resort."

What then of the artists in all this hurly-burly of tourism? Seddon, writing in the 50s, said that Cairo

is certainly a wonderful kaleidoscope and has all its beauties and some of its inconvenience? The narrow streets, so bustling and picturesque, are as inconvenient to paint in as Cheapside. The dust and crowd make oils impossible . . . the religious prejudices of the people make it difficult to persuade any respectable person to sit.

It seems that Lewis, residing in Cairo between 1842 and 1851 was one of the few artists able to live as an Oriental and to paint in complete freedom.

Two paintings by John Frederick Lewis: Left: The Bezestein Bazaar of El Khan Khali, Cairo. Right: The Street and Mosque of the Ghoreeyah, Cairo.

Paintings of the Sphinx, Thebes, Memphis, Philae, the Pyramids, the Nile Delta and Cairo itself were soon common sights at the Academy, so much so that Ruskin rather nastily remarked "Are we never to get out of Egypt any more? Nor to perceive the existence of any living creatures but Arabs and camels?"

Flaubert's Salammbo was to inspire as many artists as Gautier's Roman de la Momie; Flaubert had been infected with a longing for the exotic, especially by his reading of Byron, Hugo's Les Orientales and The Arabian Nights. Reality was evidently different, and the discomfort and boredom of photographic expeditions with his travelling companion, Maxime du Camp, drove him to distraction. However, his pantheistic love of the sun, his taste for antiquity, his curiosity concerning religions and customs, led him to a deeper understanding of the Orient.

Each artist took from Egypt what he wanted to find: a Pharaohonic or Scriptural past, episodes from the Napoleonic epic, modern Moslem life and customs, political actualities or just the light effects and colour of this infinitely varied country.

3. East of Suez

e Lamartine wrote in

Voyages en Orient that

"Chateaubriand went there as

a Pilgrim, as a Knight, the

Bible, the Gospel and the

Crusades in his hand. I,

myself, passed through merely

as a poet and philosopher."

Poets and philosophers were,

however, rare in the lands

East of Suez. In the main,

there were archaeologists and

their accompanying

draughtsmen, explorers such

as Burkhardt and Burton,

eccentrics like Lady Hester

Stanhope and Jane Digby,

Arabists and linguists, and a

stream of Victorian visitors

and theologists seeking proof

of the veracity of the

Scriptures. Indeed, for many

Victorian artists, notably

J. J. Tissot, Lord Leighton,

Holman Hunt, David Wilkie,

the main purpose of

travelling to the Holy Land

was to paint religious pictures

with their authentic

backgrounds and ethnic

types. Many were deeply

moved at the sight of

Jerusalem; others, like Lear,

were disappointed by the

mixture of squalor, poverty

and decay. "0 my nose!

o my eyes! o my feet!" he

cried. "How you have

suffered in that vile place!

For let me tell you,

physically Jerusalem is the

foulest and odiousest place on

earth." Thomas Seddon

found that the views of the

Holy Land illustrated in the

journal of the Christian

Knowledge Society were

sadly misleading, and wanted

to write reproaching them for

their "most unchristian story-telling."

e Lamartine wrote in

Voyages en Orient that

"Chateaubriand went there as

a Pilgrim, as a Knight, the

Bible, the Gospel and the

Crusades in his hand. I,

myself, passed through merely

as a poet and philosopher."

Poets and philosophers were,

however, rare in the lands

East of Suez. In the main,

there were archaeologists and

their accompanying

draughtsmen, explorers such

as Burkhardt and Burton,

eccentrics like Lady Hester

Stanhope and Jane Digby,

Arabists and linguists, and a

stream of Victorian visitors

and theologists seeking proof

of the veracity of the

Scriptures. Indeed, for many

Victorian artists, notably

J. J. Tissot, Lord Leighton,

Holman Hunt, David Wilkie,

the main purpose of

travelling to the Holy Land

was to paint religious pictures

with their authentic

backgrounds and ethnic

types. Many were deeply

moved at the sight of

Jerusalem; others, like Lear,

were disappointed by the

mixture of squalor, poverty

and decay. "0 my nose!

o my eyes! o my feet!" he

cried. "How you have

suffered in that vile place!

For let me tell you,

physically Jerusalem is the

foulest and odiousest place on

earth." Thomas Seddon

found that the views of the

Holy Land illustrated in the

journal of the Christian

Knowledge Society were

sadly misleading, and wanted

to write reproaching them for

their "most unchristian story-telling."

The Scapegoat by William Holman Hunt.

Holman Hunt, accompanied by Seddon, went to the edge of the Dead Sea, to paint his celebrated Scapegoat agonizing on the flat salt plain. Despite the intense heat, skirmishes with local tribesmen and the death of two animals, he was finally able to exhibit his picture at the Royal Academy of 1856. But he got no thanks for his labour ... "I wanted a nice religious picture," wrote the art dealer Gambart, "and he painted me a great goat." although there were a good many excellent watercolours and engravings of the landscapes and sites, few artists were able to work actually inside the mosques. However, Carl Werner painted the interior of the Mosque of Omar in Jerusalem and Gustav Bauernfeind the great Omayyade mosque in Damascus. This last city was particularly difficult for artists, as it was hostile to non-Moslems, being of great importance to the Islamic world as a point of departure for pilgrims to Mecca.

Syria and the Lebanon were somewhat more accessible after coining under the domination of the Ottoman Empire and the ruins of Palmyra and Baalbeck were very popular with artists. There were, however, many dangers for the traveller besides rapacious governors and fanatic tribesmen. Fever was widespread and in Baghdad in 1831 there was a terrible plague with 5,000 people dying each day. During the early nineteenth century, guides had been necessary and native dress more than advisable. Consuls would invite the few tourists to their houses, give them official protection on their journeys and act as their bankers. But as the number of visitors increased, so did their intrepidity. It was felt if you "went slowly and looked English" no harm could come to you. The paraphernalia considered necessary for comfortable travelling was enormous. One list reads

tents, canteen, basins, tubs, leather bottles, corks, candlesticks, lanterns, mats, carpets, kitchen apparatus, iron portable beds, mosquito nets, two portable tables, camp stools, armchair, spades, umbrella, straw hats, saddlebags, green or blue spectacles, soap in cakes, sago, apricot jam or marmalade, books

The craggy desolation of the Sinai desert held a romantic attraction for travellers surfeited with the trappings of the too westernised Oriental cities. Flaubert, writing from Constantinople, said that "Passing Abydos, I thought of Byron. That is his Orient, the Turkish Orient of the curved sword, the Albanian costume, and the grilled window looking onto the blue sea. I prefer the baked Orient of the Bedouin and the Desert."

4. North Africa

efore the taking of Algiers

in 1830 and the French

colonisation of North Africa,

the only pictorial images were

those of Barbary pirates; the

idea of young girls being

carried off to pachas's harems

excited the popular

imagination and provoked

pious indignation. The

opening up of the ancient

African continent came as a

violent shock to both writers

and painters, overwhelmed by

its mystery and richness.

While the military artists,

Yvon, Vernet, Phillippoteaux,

Raffet, Dauzats, dutifully

recorded each Governmental

victory, Delacroix, Chasseriau

and Dohedencq painted the

ethnic types, the brilliant

colours, the movement of the

crowds, with an enthusiasm

bordering on delirium.

efore the taking of Algiers

in 1830 and the French

colonisation of North Africa,

the only pictorial images were

those of Barbary pirates; the

idea of young girls being

carried off to pachas's harems

excited the popular

imagination and provoked

pious indignation. The

opening up of the ancient

African continent came as a

violent shock to both writers

and painters, overwhelmed by

its mystery and richness.

While the military artists,

Yvon, Vernet, Phillippoteaux,

Raffet, Dauzats, dutifully

recorded each Governmental

victory, Delacroix, Chasseriau

and Dohedencq painted the

ethnic types, the brilliant

colours, the movement of the

crowds, with an enthusiasm

bordering on delirium.

As immigration was intensified and colonisation completed, so the number of artists in North Africa increased. Many, notably Roberts, Lewis, Regnault and Clairin, went first to Moorish Spain. Fromentin and Guillaumet painted the open skies, the implacable light and the overwhelming vastness of the desert, their simplicity and economy of style placing, them at the head of the second generation of African Orientalists.

During the 1880s and 90s, legions of painters set off across the Mediterranean, "their souls filled with sunlit dreams" (Dayot). Moucharabies and marabouts, the twisted columned suks of Tunis, the red gorges of El-Kantara and the arcades of the Place de l'Amirauté in Algiers became as well-known to Salon visitors as Breton coifs, the Mont St. Michel or the Forest of Fontainebleau. The last French Orientalist in the nineteenth century sense was Etienne Dinet, known, after his conversion to Islam as Hadj Nasr Ed Dine Dini. Acclaimed by the Algerians as one of their own, Dinet was one of the few painters to be able to lift the veils behind which the Orient has always hidden.

5. Odalisque and Slave

n Victorian times, the

hypocritical horror of the

nude did not come from a cult

of chastity, but seemed

rather more to have been part

of the enormous facade of the

nineteenth century, with its tacit

code of respectability. One

could hang pictures or show

sculptures of nudes but it

would be bad taste to mention

an ankle. A nude could mean

two things; pictorial ideal or

erotic provocation. In the

first case, the continued

admiration of classical art

allowed representations of the

perfect goddess-nude,

particularly acceptable in

mythological, Greek or

Roman settings. In the

second, it was possible to

paint more realistic nudes, but

in exotic or historical

contexts. Manet's Dejeuner

sur Herbe, with a naked

woman surrounded by men in

contemporary clothes,

outraged public opinion, as he

had not had the decency to

camouflage the obvious

eroticism.

n Victorian times, the

hypocritical horror of the

nude did not come from a cult

of chastity, but seemed

rather more to have been part

of the enormous facade of the

nineteenth century, with its tacit

code of respectability. One

could hang pictures or show

sculptures of nudes but it

would be bad taste to mention

an ankle. A nude could mean

two things; pictorial ideal or

erotic provocation. In the

first case, the continued

admiration of classical art

allowed representations of the

perfect goddess-nude,

particularly acceptable in

mythological, Greek or

Roman settings. In the

second, it was possible to

paint more realistic nudes, but

in exotic or historical

contexts. Manet's Dejeuner

sur Herbe, with a naked

woman surrounded by men in

contemporary clothes,

outraged public opinion, as he

had not had the decency to

camouflage the obvious

eroticism.

Orientalism provided the ideal excuse to paint nudes, but since Moslem women would not sit for the artists, they were usually hired models posed in the studio, with suitable eastern accessories. The rising class of industrialists, throwing aside the pruderies of the capital, found it cheaper and safer to buy works by living artists. These erotic pictures gave them an official excuse to enjoy scenes of odalisques and dancers, chained slaves, public baths and harems, with overtones of rape, brutality and sensuality.

Most nineteenth century artists and writers visited the Cairo slave markets. Maxime du Camp wrote that "when the dahabeeahs return from their long and painful journeys on the Upper Nile, they install their human merchandise in those great okels which extend in Cairo along the ruined mosque of the Caliph Hakem; people go there to purchase a slave as they do here to the market to buy a turbot." William Muller, although saying that the scene was of a "revolting nature," felt

more delight in this place than in any other part of Cairo . . . The slave-market was one of my favourite haunts . . . one enters this building which is situated in a quarter the most dark, dirty and obscure of any at Cairo by a sort of lane ... in the centre of this court, the slaves are exposed for sale and in general to the number of thirty to forty, nearly all young, many quite infants. The scene is of a revolting nature; yet I did not see as I expected the dejection and sorrow as I was led to imagine . . . when anyone desires to purchase, I not infrequently saw the master remove the entire covering of a female — a thick wollen cloth — and expose her to the gaze of the bystander

Many visitors were anxious to watch the Gházeeheh dancers or to hear the A'l'mehs — the female singers. But Mehemet Ali had passed an edict in 1834 forbidding dancing and prostitution in Cairo, and it was necessary to go up the Nile in order to see the Gházeehehs. Flaubert wrote enthusiastically about the archaistic nature of their dance, certainly descended from Pharaohonic times, but Muller found "it partakes so strongly of the lascivious nature as to be disgusting."

Outsiders could not of course visit the harems, but they were able to get enough information in order to describe them vividly. Popularly imagined as places of debauchery, they were in fact morally and socially well-organised. The harem consisted of up to four wives, female slaves who were generally concubines, slaves of slaves, nearly all blacks from Sudan, called calfas, and free female servants. The legitimate wives would invite the slave-mothers to their private quarters to play cards or tric-trac; sewing, embroidery and weaving were other favourite occupations during idle hours. Only the master and the eunuchs, nearly all Nubian or Sudanese, could penetrate into the intimacy of the harem.

The public baths also attracted the attention of many visitors. One went through a vestibule and a series of warm rooms into the centre, where a fountain of tepid water splayed. There, one was massaged, scraped and pumiced. In an adjoining room, one was rinsed, left to rest on mattresses, given coffee, kif, and told the latest stories. The baths were open to men in the morning, but the rest of the day was reserved for the women. They came to gossip and sometimes to form harem intrigues. Several of them were accompanied by their slaves who would rub them down.

What could be more delicious than these sensual pleasurable pastimes to the industrious, dutiful people of the North?

Bibliography

Eastern Encounters: Orientalist Paintings of the Nineteenth Century. London: The Fine Art Society, 1978.

Created 30 December 2004

Last modified 19 October 2021