Sir John Everett Millais, one of the three principal founding members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood along with William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, displayed precocious talent at a young age, gaining the reputation of a child prodigy. At the age of eight, Millais won the silver medal of the Society of Arts, which drew further encouragement from his parents who moved to London in order to provide increased training for their son. However, despite the numerous years he spent attending Royal Academy schools, upon meeting Hunt and making the acquaintance of Rossetti, he joined with his friends in an artistic alliance that shunned the art world's contemporary rigid conventions, such as "subdued colors" (Millais 14) and pyramidal compsition. This desire to counter the principles advocated by the Academy in favor of a fresh naturalistic art ultimately led to the formation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848. PRB aesthetics, thus, stemmed from the artists' "resistance to academic rules of representation and composition" (Codell 120) and their admiration for the art critic John Ruskin's "emphasis on the truth and beauty to be found in nature, and the purity of the earlier Italian masters" (Bennett 5). Millais emerged as the most talented artist associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which followed Ruskin's ideal of picturing nature in its likeness and wonderment. Though Millais initially included detailed renderings of nature to augment the poetic nature of his figurative paintings, he later devoted himself increasingly to landscape as he noted that "'you can so completely please yourself as to what you do in landscape; you have only yourself to satisfy'" (Spielmann 58). Therefore, his great ability to create photographic representations of nature and the various ways in which Millais incorporated nature in his works act as elements that contribute to his enduring legacy as a distinguished and renowned artist.

Millais's involvement with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood created lasting influences that permeated the works that Millais produced during his career. For example, Millais and the other Pre-Raphaelites harshly criticized the convention of using "subdued colors" in artworks. The Academy in return denounced their use of a bright palette, declaring that these colors appear "crude and vulgar," and supported an inoffensive color scheme (Millais 14). However, as Millais notes the ignorance of men who will not include such colors as bright green in their works, he declares "God Almighty has given us green, and you may depend upon it it's a fine color" (Millais 14). Thus, the Pre-Raphaelites sought to paint using bright, illustrious colors and eliminated the incorporation of shadows with the intent of illuminating the entire painting, which often gave an impression of flatness (Landow).

In addition, the hard-edge photographic realism of the early Pre-Raphaelites developed as a direct contradiction to the conventions of the Royal Academy. The Academy supported neoclassical theories of representation that involved giving impressions of a particular object rather than pointedly expressing each detail. However, the Pre-Raphaelites considered attention to natural detail a critical element of painting. Hence, by painting each object, including those that traditionally did not merit much worthiness, with meticulous attention to detail as well as using a bright color palette, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood successfully abandoned the conventional notion of chiaroscuro. Therefore, the two most important and obvious components of Pre-Raphaelite naturalism include "minute detail and and bright color with a minimum of shadow" (Landow).

A work that clearly displays Millais's superiority in creating photographic representations of nature is John Ruskin, Esq., a portrait that Millais created of the man that singly provided the most influence to the members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Ruskin idealized the faithfulness with which an artist should represent naturalistic detail, and the Pre-Raphaelites' desire to maintain this faithfulness in their works won the support of the art critic. Millais successfully creates a photographic representation of Ruskin himself. Ruskin is depicted with a posture that appears natural, which reflects Millais's careful studies of anatomy and expression (Codell 121). The facial features of Ruskin appear individualized as careful brushstrokes portray and highlight Ruskin's complexion and the natural lines that outline each aspect of his face. Millais also devotes time to integrate elaborate details to the accessories of the figure, such as the clothing and the hat Ruskin carries. The meticulous coloring that Millais applies to the pants as well as the curves of Ruskin's hat to accentuate the realism of the portrait clearly reflects PRB and Ruskinian ideals.

A work that clearly displays Millais's superiority in creating photographic representations of nature is John Ruskin, Esq., a portrait that Millais created of the man that singly provided the most influence to the members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Ruskin idealized the faithfulness with which an artist should represent naturalistic detail, and the Pre-Raphaelites' desire to maintain this faithfulness in their works won the support of the art critic. Millais successfully creates a photographic representation of Ruskin himself. Ruskin is depicted with a posture that appears natural, which reflects Millais's careful studies of anatomy and expression (Codell 121). The facial features of Ruskin appear individualized as careful brushstrokes portray and highlight Ruskin's complexion and the natural lines that outline each aspect of his face. Millais also devotes time to integrate elaborate details to the accessories of the figure, such as the clothing and the hat Ruskin carries. The meticulous coloring that Millais applies to the pants as well as the curves of Ruskin's hat to accentuate the realism of the portrait clearly reflects PRB and Ruskinian ideals.

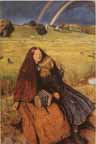

However, Millais's landscapes and reproductions of nature do not merely serve as tributes to geology and Ruskin's teachings, but they also enhance the messages and symbolism that Millais sought to convey in his typologically symbolic works, such as The Blind Girl. Millais fuses elements of both figurative and landscape paintings in order to create The Blind Girl. Although the figures of the two girls depicted along the side of the road clearly act as the main focus of the painting, the landscape and various objects of nature that Millais employs appear indispensable to the work. In The Blind Girl, Millais continues to abide by the Pre-Raphaelite notion of creating photographic representations, and the result reveals painstaking attention to detail and a light source that evenly highlights all aspects of the colorful painting. For example, the hair of the younger girl who turns away from the viewer to observe the rainbow actually appears to incorporate individual strands, which enhances the realistic nature of the figure. The outfits that the girls wear also display exquisite detail as Millais carefully depicts the rips and tears as well as the threading in the skirts of the two girls.

Again, like John Ruskin, Esq., the emphasis on realism as endorsed by the Pre-Raphaelites extends beyond the focal subject into the landscape. Millais paints the individual blades of grass and weeds near the blind girl's hand with meticulous care as well as the butterfly that rests on her cloak. However, unlike John Ruskin, Esq. in which every inch of the canvas involves the same level of painstaking detail, in The Blind Girl, Millais seems to subtly depart from complete minuteness. As the viewer's eye moves away from the foreground that the two girls inhabit, the landscape's details become increasingly less fastidious though Millais successfully gives off the impression of precisness that pervardes John Ruskin, Esq..

Moreover, Millais uses the background to explain the meaning of his work. The double rainbow in the background that emerges from Millais's landscape serves as a symbol of beauty that the blind girl cannot witness in her current state but will be able to encounter in another world perhaps as a reward for her suffering. Thus, the presence of the rainbow and the butterfly emphasize "the full affliction of loss of sight and the supreme consolation of the Divine promise" (Spielmann 31) and how "Christ will raise the girl with new and better vision" (Landow). In addition, the overall landscape lends The Blind Girl a hopeful mood despite the rain that appears to have previously prevented the two girls from continuing their route. Though the dark clouds still cover the expanse of sky in the background, the warm light that envelops the two girls and begins to stretch towards the town and the fields by which they sit suggests a sense of calm, comfort, and beauty. Therefore, it appears that the landscape serves as a method for Millais to saturate the painting with mood and emotion as well as to offer more clues to understand the religious and biblical allusions of the work rather than merely acting as a means to create photographic representations of nature.

Moreover, Millais's embedding of nature in his paintings concerning romantic, tragic love like Ophelia also indicates the importance of backgrounds in conveying this particular theme that often engrossed the Pre-Raphaelites. Millais realizes Shakespeare's play, Hamlet, in his meticulous interpretation of Ophelia's death. Millais takes a surprising route by depicting Ophelia as she drowns to her death, sinking slowly in the pool of water that increasingly envelops and will eventually completely overwhelm her body. The expression on Ophelia's face as well as the placement of her hands reflect the Pre-Raphaelite interest in the study of anatamy and expression more so than the positioning of Ruskin on John Ruskin, Esq.. Her slightly open mouth imparts a sense of eroticism, which highlights the beauty of the figure. In addition, the blank stare of her eyes shows how Ophelia has resigned herself to the situation and subsequently, her death. Furthermore, the careful attention paid to the Ophelia extends beyond her body to the elaborate embroidered dress that she wears. The viewer can perceive the exquisite nature of the dress's intricacy embroidery, particularly on her bosom, as well as the folds in the gown as it becomes submerged underwater.

However, as in The Blind Girl, the solitary figure of Ophelia itself does not communicate the effect that Millais strives to create, but rather, the detailed landscape that surrounds the dying Ophelia helps to augment the tragic nature of the situation. Millais conceives a lush, green background that includes the following flowers: violets, pansies, and poppies The painstaking details that Millais endows on these flowers, which float on top of the water as Ophelia slowly releases them from her grasp and line the edge of the pool, emphasize the conception of fragility that they generally represent (Codell 136). For example, violets represent the "faithfulness, chastity, death of the young; pansies as love in vain and thought; poppies as death" (Codell 136). Therefore, though Ophelia has not yet died in the specific moment that Millais chooses to render, the presence of the flowers foreshadows the doomed destiny of Ophelia. Additionally, the landscape of greenery that encloses the location of Ophelia's inevitable death appears to play an accompanying role to this tragedy. Setting Ophelia's death against a natural backdrop that would ordinarily appear beautiful indicates how Millais desires that the viewer comprehend the atypical, tragic essence of this youthful woman's suicide and death. The immaculate detail with which Millais paints the tall vegetation near Ophelia's head, the branches of the shrub along the bank, and the algae that floats alongside her dress all appear to show how she will be engulfed by nature upon her death. The background also seems to intensify the solitude in which the death occurs. No living being but the plants and trees exist to witness Ophelia's suicide. Therefore, Millais uses the landscape of Ophelia to heighten the effects of the tragedy caused by failed romantic love.Ultimately, Millais's ability to reproduce nature with meticulous attention paid to even the most minute details as well as his interest in naturalistic studies later culminated in his pursuit of painting pure landscape paintings "between 1870 and 1892, during the mature phase of his artistic career" (Helmreich 149). Millais's first pure landscape painting, Chill October reflects his attempts to pursue nature solely and not use it as a mere background to highlight and strengthen the figurative subjects that dominated his art work earlier in his career. After its exhibition at the Academy, Millais became further recognized by admirers and enhanced his popularity as critics noted and praised his immense versatility (Baldry 56). Despite achieving additional fame, Millais's pure landscapes did not only return positive responses. Rather, others charged that his landscapes seem to exist only as painted photographs that do not capture emotion or create a sense of atmosphere. Ruskin himself, in an essay published in 1859, proclaimed that "Millais lacked the inventive power of Turner while possessing stronger powers of observation" (Helmreich 158). Drawing from J.D. Harding's theories regarding landscapes, Ruskin explains that "'the landscape painter must always have two great and distinct ends: the first to induce in the spectator's mind the faithful conception of any natural objects whatsoever; the second, to guide the spectator's mind to those objects most worthy of contemplation, and to inform him of the thoughts and feelings with which these were regarded by the artist himself'" (Landow). It remains clear that Ruskin nor other critics denounced the masterful techniques of representation that Millais unequivocally possessed, which had been duly noted during the course of Millais's career. Yet, Millais's ability to convey emotion through landscape alone appears to was highly doubted by many.

Similar criticism streamed in from other sources besides one of the original mentors of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. For example, Baldry also notes that Millais's landscapes lack "the imaginative insight into poetic subtleties which accounts for so much in the work of a master like Turner" despite the brilliance with which Millais is able to carefully depict nature (Baldry 57). Baldry goes even further to suggest that Millais hardly ever attempted "the touch of fantasy, of actual unreality, by which the inspired landscape painter seems to suggest more truly the real spirit of nature" nor did he ever succeed (Baldry 61). Therefore, Ruskin and other critics appear to claim that Millais did not fulfill the requirements of being a master landscape painter due to his inability and unwillingness, as Baldry charges, to evoke emotion and feeling in his pure landscapes.

Although many critics have charged that Millais's landscape paintings merely reflect an imitation of nature, others argue that poetic feelings actually do resonate within these works and that Millais does not merely transcribe nature onto a canvas (Mancoff 14). This seems to correlate with William Holman Hunt's assertion that the intent of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood does not solely involve "offer[ing] prosaic, static transcriptions of natural objects" (Codell 120). Millais himself remains consistent when offering his support of Hunt's statement that Pre-Raphaelite naturalism does not simply act as a study of surface details; rather, Pre-Raphaelite naturalism acts as a study of change to capture the "complex field of shifting forces: emotional, psychological, social and historical" (Codell 133). In responses to the criticisms that accused Chill October of existing only as a photographic representation of nature, Millais countered that he "'chose the subject for the sentiment'" (Codell 140). This statement in itself suggests that Millais would naturally desire to convey this sentiment rather than simply transferring the view with the techniques that involve immaculate, meticulous details. In fact, Millais expressed dissatisfaction and unhappiness with painting in microscopic detail due its time-consuming nature (Codell 141). Thus, Pre-Raphaelite naturalism does not seem to merely embody the painstaking detail with which artists such as Millais utilized to create their paintings. Rather, it also inherently involves an emotive element, according to the two of the principal founding members of the Brotherhood, Hunt and Millais. Therefore, the pure landscape paintings of Millais also appear to possess this element despite stinging acknowledgements that they only serve as exact blueprints of nature.

In Chill October, the sheer expanse of landscape that fills the canvas appears to create a mood of melancholy while portraying the transience of life that also embodies other works by Millais. The absence of figures allows the viewer to concentrate solely on the full landscape, which remains in stark contrast from Millais's earlier use of landscapes to accentuate the subject at hand. For example, one cannot deny the significance of the background in Autumn Leaves. By depicting the leaf-gathering and burning session at sunset (Ruskin lauded this portrayal, calling it "the first instance of a perfectly painted twilight" [Walker Art Gallery catalogue, 42]), Millais emphasizes how the youthful nature of these girls are also at the mercy of the transience of life. The sun that sets over the landscape acts an indicator for the sunshine of life that will inevitably set over the life of each of these girls. However, despite the importance of the background of this meaning "is conveyed largely through the young girls, whose frail beauty is accentuated by the setting" (Helmreich 153), whereas the landscape in Chill October alone illustrates this theme.

In Chill October, however, Millais does not rely upon figures to reveal the transience of life through melancholic beauty. The palette of yellows, greens, and browns that Millais uses to recreate a view of Scotland near Perth and Dunkeld (Helmreich 151) perpetuates this somber mood. Moreover, Millais portrays a view in which the wind blows to the left. The brown marsh grasses in the foreground of the painting follow the course of the wind as do the dark trees in the background. The steady movement caused by the window indicates that life is not static, but rather always in motion. Thus, this furthers the suggestion that Chill October seeks to evoke transience. The uprooted tree trunk that lies in the bottom left corner of the canvas also appears to "signify death and loss" (Helmreich 153). However, the painting does not solely depict death and loss but actually appears to impart hopefulness as well due to the beauty of the scene and the sense of calm that envelops the landscape. In addition, the autumnal setting of Chill October contributes to the mournfulness and suggests a "transience of beauty" and life, which clearly invokes the theme that Millais explores in Autumn Leaves (Helmreich 153). Therefore, it appears upon observation that many of Millais's pure landscape paintings reflect the notion of transience and mortality that often embed his figurative paintings, such as Autumn Leaves and The Vale of Rest. Yet, in Chill October the landscape serves as the prime vehicle for communicating meaning and expression. Despite arguments that Millais's pure landscapes are solely photographic representations that involve meticulous attention to detail by renowned critics such as Ruskin, it appears that there, in fact, exists an emotive element that these unfavorable responses.

Another example of a pure landscape painting that seems to discount criticisms that Millais lacks the talent to convey "the real spirit of nature" (Baldry 61) is Dew-Drenched Furze. Millais again uses autumn, a season that evokes the feeling of transience and reminds viewers of nature's mortality, for the setting of his painting. However, unlike Chill October, Dew-Drenched Furze appears to focus more on the hopefulness that nature provides rather than its transience. The color palette that Millais utilizes appears similar to the one used in Chill October, but he paints with lighter versions of these same colors, which brightens the landscape. Moreover, the light that shines over the landscape emanates warmth and calm that allows the viewer to perceive Millais's advocacy of nature's inherent hopefulness. In addition, the dew that soaks the branches and the reeds reminds the viewer of morning, which elicits a sense of new awakening. These elements combine to create an ethereal sense of beauty, and Millais appears to evoke the hope that new life will always emerge in nature. Therefore, Millais does not seem to be the landscape painter that merely transcribes landscapes and lacks imaginative qualities, but he appears to create evocative portrayals of the scenes of the outside world.

Exploring Millais's works that incorporate landscapes as well as those that involve landscapes alone reveals Millais's innate talent in successfully capturing individual elements of nature and then fusing these elements into an entire canvas. Millais clearly carries out the two predominant components of Pre-Raphaelite naturalism--the application of minute details and a bright color palette with minimal shadows--with much success. Despite allegations that he lacks the ability to evoke feelings in the absence of figures in his pure landscape paintings, the way in which he utilizes backgrounds in his typologically symbolic pieces as well as his works involving tragic love and the transience of life In addition, observing Chill October and Dew-Drenched Furze indicates that Millais does not endeavour to merely create photographic representations using the Pre-Raphaelite ideal of hard-edge realism, but that he also seeks to convey meaning through his backgrounds and landscapes. Therefore, Millais expresses the poetry and grandeur of nature through Pre-Raphaelite naturalism not only in his figurative, thematic paintings but also in his pure landscape paintings that he created later on in his career.

Bibliography

Baldry, A.L. Millais London: T.C. nd E.C. Jack; New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1908.

Codell, Julie F. "Empiricism, Naturalism and Science in Millais's Paintings." John Everett Millais: Beyond the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood Ed. Debra N. Mancoff. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001. 119-147

Helmreich, Anne. "Poetry in Nature: Millais's Pure Landscapes." John Everett Millais: Beyond the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood Ed. Debra N. Mancoff. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001. 149-179.

Landow, George P. "J.D. Harding and John Ruskin on Nature's Infinite Variety." The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 38 (1970). The Victorian Web.

Landow, George P. "Pre-Raphaelites: An Introduction." The Victorian Web.

Landow, George P. "Rainbows: Problematic Images of Problematic Nature." Images of Crisis: Literary Iconology 1750 to the Present. Boston and London: Routledge, 1982. The Victorian Web.

Landow, George P. "The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple and Pre-Raphaelite Compositional Themes." William Homan Hunt and Typological Symbolism. New Haven and London: yale UP, 1979. The Victorian Web.

Mancoff, Debra N. "John Everett Millais: Caught Between the Myths." John Everett Millais: Beyond the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood Ed. Debra N. Mancoff. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001. 3-19.

Millais, Sir John Everett. "Thoughts on Our Art of To-day." Millais and His Works. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1898.

Spielmann, M.H. Millais and His Works. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1898.

Walker Art Gallery. Millais: an Exhibition Organized by the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, and the Royal Academy of Arts. London, January-April, 1967. Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery; London, Royal Academy of Arts: 1967.

Wood, Chrisopher. The Pre-Raphaelites. New York: Studio/Viking, 1981.

Last modified 21 December 2004