Left: For Sale [At the Bazaar; The Empty Purse], by James Collinson (1825-1881). 1857. Oil on panel. 33 1/4 x 27 15/16 inches (84.4 x 70.9 cm), oval shaped. Collection of Graves Art Gallery, Museums Sheffield, accession no. VIS.11. Image reproduced via Art UK for the purpose of non-commercial research. Right: For Sale. Oil on canvas. 23 x 18 inches (58.4 x 45.7 cm), oval shaped. Collection of Nottingham City Museum & Galleries, accession no. NCM 1959-94, reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial licence (CC BY-NC).

The principal version of this work was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1857, no. 115. This is the painting now at the Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield. Ronald Parkinson has noted that there are five known versions of this painting, "all are almost identical (the only difference is that the words 'Follow Me' are missing from the print of The Way to Calvary in two of the versions), and four are approximately the same size (the fifth is quarter size)" (74). The two versions that lack the phrase "Follow Me' are the ones at Philadelphia and Nottingham. The version at Sheffield known as At the Bazaar bears the words "James Collinson Printer" at the bottom of the yellow handbill advertising the sale of work (Cox, 7). Tthe replica in the collection of the Tate Britain is entitled The Empty Purse (accession no. N03201). This work is 24 x 19 3/8 inches (61 x 49.2 cm) in size. The version in the Philadelphia Museum of Art from the Mcllhenny Collection is 23 x 18 inches (58.4 x 45.7 cm) in size. A small study for For Sale sold at the John Schaeffer sale at Christie's, London on July 29, 2020, lot 64. This version was only 12 x 9 ¾ inches (30.5 x 23.8 cm) in size and was once in the Forbes Collection where it sold at Christie's on February 20, 2003, lot 98. Parkinson felt this small version might possibly be a copy by another artist but it is signed by Collinson so more likely was a preliminary study based on what Beresford has described as its "freer and livelier" style (38). It was not unusual for Collinson to re-title works that had failed to sell in London exhibitions when he exhibited them in provincial centres but was more unusual to re-title different replicas of the same picture.

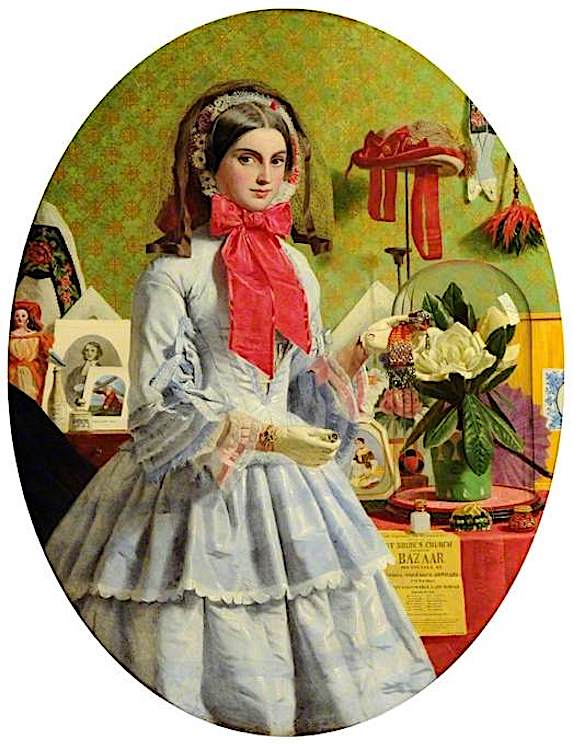

The painting features a fashionably dressed young woman, somewhat younger than the one pictured in To Let. She is standing upright looking directly outwards towards the viewer and clad in a full-length dress of a light blue and pale grey material with a large red bow tied at her neck. Her bonnet has a dark veil, which is drawn back over her head. She is wearing white gloves and holding what has been described as either a ring or a thimble in her right hand and an apparently empty, fancy embroidered and beaded purse in her left. She is at a church bazaar where Beresford has described her surroundings:

As the paper besides her tells us this is St. Bride's Church Bazaar for the sale of [use]ful and fancy articles Patroness [the] honourable Lady Dorcas. On the table are ranged a variety of goods for sale, many of which would have been duly crafted for charitable purposes by the daughters of well-to-do households. The objects include a doll in 17th- or 18th- century costume, a portrait print or drawing of an ecclesiastic, a small colour print of Christ on the way to Calvary inscribed FOLLOW ME, a wax flower under a glass dome, a parasol, a wooden box labelled BRICKS (a child's toy?), a straw hat decorated with red ribbons, an elaborately decorated pair of braces and a feather duster. The name "Lady Dorcas" is a reference to various Victorian Dorcas societies composed of women who, sometimes unable to give money, donated their time to make clothes for the poor, naming themselves after the original Dorcas of the Bible. [38]

The story of Dorcas can be found in Acts 9: 36-42. She was a woman who followed Christ's teachings and made clothes for widows and the poor. Collinson's religious views are also reflected in the coloured print of Jesus bearing the cross inscribed "Follow me." Other objects in Collinson's painting can be seen on the table covered with a red tablecloth, in front of the large glass dome, including a small jar, a casket, and a paperweight. Behind the domed plant is a portrait of a woman, a small chequered ball, and a fan. Parkinson feels while "most of the objects for sale at the bazaar seem to me mainly remarkable as ordinary and innocuous, some of the details may have a significance" (75). Rosemary Treble, for instance, mentions "the doll at the far left, dressed in eighteenth century finery, is probably a comment on the superficial nature of fashion and its followers" (28).

Berenson noted there has been speculation that Collinson intended the title For Sale to have a double meaning, and that the woman is, in some sense, the item "for sale": "It seems inevitable that a picture of an attractive young woman holding a ring in one hand and a purse in the other and standing next to a poster announcing 'St. Bride's Bazaar' would have suggested in some minds the idea that she might be 'on the marriage market.' It was perhaps because he actively wanted to discourage this reading that Collinson later found alternative titles for the image: At the bazaar and The empty purse" (38). Newman has commented on this controversy, too: "there is also the question of whether James' somewhat ambiguous titles were deliberate or not. Did he, for instance, intend a moral message to be read into them, or had this possibility never occurred to him?" (116). Parkinson noted that Collinson was "apparently distressed when the public interpreted the title of "For Sale … as a description of the girl" (74-75). Newman has given the fullest discussion of the possible interpretations of this painting and its companion To Let, noting how "religious and sexual connotations can be applied to both" (118). Susan Casteras has provided a more modern feminist possible interpretation of this painting (55).

When For Sale and its companion To Let were shown at the Royal Academy in 1857 a critic for The Literary Gazette failed to be impressed calling them "A pair of subjects…representing two specimens of vulgarity in the shape of a showy landlady and a lively saleswoman, are attractive at a distance from their smart drawing and bright colour; but are hung too high to allow of any certain estimate being formed of their merits" (499).

Bibliography

At the Bazaar. Art UK Web. 2 March 2024.

Beresford, Richard. Victorian Visions: Nineteenth-Century Art from the John Schaeffer Collection. Sydney: Art Gallery of NSW, 2010, cat. 5, 38-39.

British and European Art. London: Christie's (20 July 2020): lot 67. https://onlineonly.christies.com/s/british-european-art/james-collinson-british-1825-1881-67/92263>/p>

Casteras, Susan Ed. The Defining Moment: Victorian Narrative Paintings from the Forbes Magazine Collection. Charlotte, North Carolina: Mint Museum of Art, 1999, cat. 9, 54-55.

Cox, Valerie A. "The Works of James Collinson: 1825-1881," The Review of the Pre-Raphaelite Society IV, no. 3, (1996): 6-7.

For Sale. Art UK Web. 2 March 2024.

Forbes, Christopher. The Royal Academy Revisited. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1975. 30.

The Forbes Collection of Victorian Pictures and Works of Art . London: Christie's (20 February 2003): lot 98, 130-31.

Newman, Helen D. James Collinson (aka "The Dormouse"). Foulsham: Reuben Books, 2016. 116-20.

Parkinson, Ronald. "James Collinson." in Leslie Parris Ed. Pre-Raphaelite Papers. London: Tate Gallery Publications 1984. 74-75.

"The Royal Academy Exhibition." The Literary Gazette XLI (23 May 1857): 499.

Treble, Rosemary. Great Victorian Pictures, their paths to fame. London: Publications Dept. Arts Council of Great Britain, 1978, cat. 5, 28.

Created 2 March 2024