Canal navvies, rough and lowering but not yet thought monkey-like, began by calling themselves Excavators, Cutters, Diggers, Bankers, and Navigators (because they made inland navigations). When navigator was shortened to navie or navey, nobody knows. Navvy — so spelt — was first used in print in the 1830s. In the 1850s they called themselves Pinchers and Bankers, as well as navvies and navigators. By the 1870s they were Thick Legs and Blue Stockings, as well as navvies. By the 1890s they were Bill Boys, Tradesmen, Excavators, and navvies. In the twentieth century they were Pick-and-Shovel men, men who followed public works (the posh phrase, that, for polite society) and navvies.

For each other they had a whole welter of nicknames which spanned the entire navvy era. Brindley's proto-navvies on the Bridgewater Canal had them: Busick Jack, Bill o' Toms, Black David, and in 1932 a navvy woman could still advertise for her runaway husband by his nickname of Shakey Joe. Most incorpo- rated place-names, like peers' titles: Cumberland Ike, Lincoln Tom, Nottingham Rags, Cheshireman, Dover Curly. In 179$ North- amptonshire Tom, a man who terrorised every county he lived in, was arrested for rioting in Leicestershire. Cousin Jack was a Cornishman. Geordie came from the Tyne's north bank. Lane or Lank came from Lancashire, though he could be a lanky man as well. York/Yorkie came from Yorkshire. Less obviously Waxie was from Northamptonshire (from the wax used in the leather trade?). Clanger came from Bedfordshire and was named after a local sand- wich, a convenience meal in itself, beginning at one end with meat and ending in pudding at the other. Veg was stuffed in between.

Moonrakers were Wiltshire men. Once, one night when the water was bright with moonlight, revenue officers surprised smugglers raking contraband from a Wiltshire village pond. The smugglers quick-wittedly pretended to be village idiots raking the moon's bright reflection from the water.

Taff was a Welshman, but so less frequently was Moutainpecker. Herdwicks, like the sheep, came from Westmorland and there were never many of them. Suffolk men were sometimes called Punch after their own big horses, though more usually Punch was a description of size and shape. Wide shouldered, stumpy men, squat like Judy's husband, were Punches. Many names, in fact, described the man himself: his intact bits or his missing bits, it didn't matter which. Peg or Peggy had a wooden peg in place of a leg. Chump also only had one leg - chump, like chump-chop, being the blunt end of something that's been sundered. Wingy was one-armed, and had been on the canals. Gunner, when he wasn't an old artillery man, was one-eyed, so called because he was ready-made for aiming a gun. 'They've got one eye closed already,' said a mid-century navvy, 'and they've no occasion to shut he.'

Tweedle Beak had a great parrot-bill/eagle-beak nose, as had Snipe. Duke, too, was nosed like his namesake, the Iron one. Slen, a common name for a slim lean man, was short for Slender or Slenderman.

Some names described character: Scan, short for scandalous, was so common it's a mystery how so many navvies managed to scandalise so many others as to earn it. Some described personal habits, like Swillicking Dick who swillicked himself to death with ale at a dam on the moors above Accrington in 1887. Some were ironic: Primrose who navvied near Kirby Stephen in the late i8^os was a most unflowerlike, scruffy ruffian. Some seemed to go in fashions: Rainbow Ratty, Fatbuck, Hopper, Chinaman, Beer, and Brandy were popular in the '70s but not noticeably so at other times.

Gorger gorged a shoulder of mutton at a sitting. Hedgehog looked like a hedgehog (snouty face? spikey hair?). Uncle Ned was forever singing Uncle Ned, a. minstrel song. Rush, the name of a well-known Victorian murderer, was given to an unknown navvy for no known reason. Cat's Meat had been in the cat's meat trade (presumably selling dead cats, not pet food). Graze-the-Field almost literally grazed the fields for a year when he was out of work, living on stolen vegetables and fruit.

Which is all very well and mostly understandable, 'But why,' asked the Rev Daniel Barrett, 'Skeedicks, Acamaraclous, or Okem-finny Joe?' Unless Okem-finny was a corruption of oakum-fingered and was a nickname for an old lag or seaman, [24/25] nobody seems to know. Why Pupe, an obscure obsolete word for a ([Bid of snail? Why Johnny-up-the-Steps? Why Standing-up- sitting-down-shitting Scan, a poacher so skilled it was said he could entice rabbits from their warrens on the Westmorland fells?

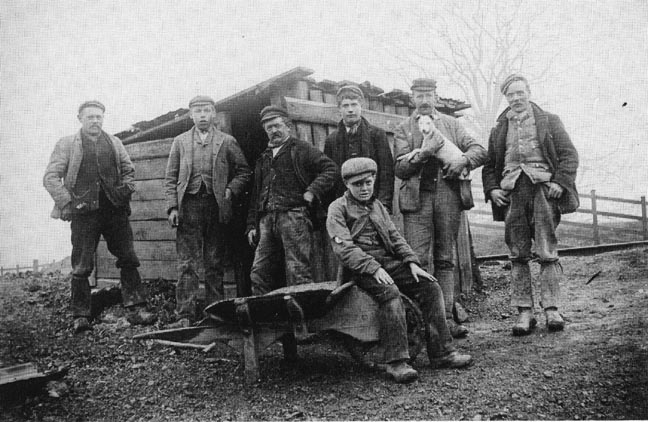

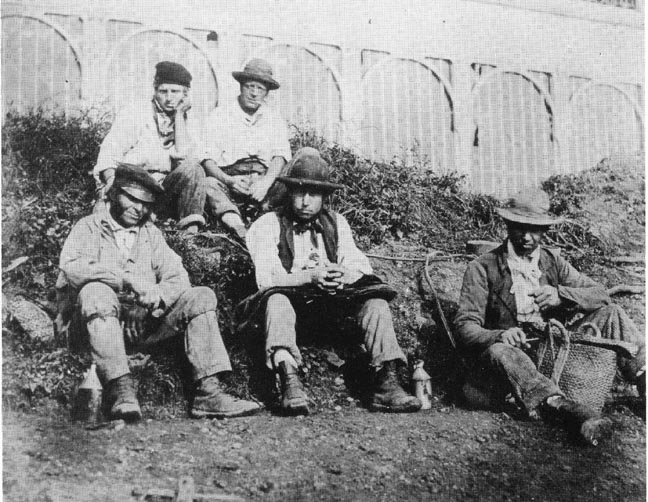

Nipper with navvies outside tommy cabin, 1890s.

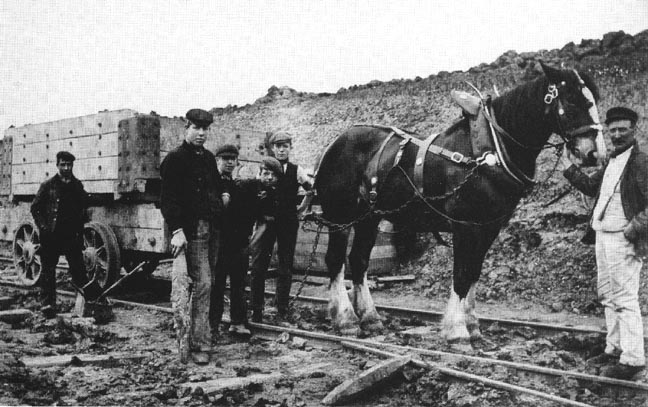

Nippers on the Grand Central Railway, 1890s

Click on thumbnail for larger image.

Food to the navvy was tommy and he carried it to work in a tommy handkerchief, generally red with white spots. Tommy was bought in tommy-shops and the provident and non-mooching carried it on tramp in straw bags called pantries. At work navvies drank tea, either brought cold in a tea bottle or made on site in a can called a drum. A drum could be anything: a biscuit tin with a wire handle, perhaps. Making tea was drumming up.

A nipper was a boy (any boy, all boys) and drumming up was a nipper's job. Usually it involved a dented tea-bucket and a certain amount of ritual. After screwing the half-filled bucket into the flame of an open fire, the nipper circulated among his navvy-clients collecting the tea and sugar which each man brought ready-mixed in his own Colman's mustard tin. The nipper emptied each tin, one by one, into the bucket, following it with a cup of cold water. (An engineer once asked why? 'To tempture it,' he was told).

Navvies with metal tea bottles, 1853. Click on thumbnail for larger image.

Tea bottles were usually metal, bottle-shaped, with a metal ring-handle near their wide mouths. They were stoppered with corks, or wads of folded newspaper when they got lost. At work you either drank your tea cold, drummed it fresh, or reheated cold tea by sticking the tea bottle in the fire, in which case the tea bottle itself became a drum. In tunnels, tallow from the candles was often used as a drumming-up burner. On some dams, later, some contractors supplied coppers of boiling water in special tommy- cabins.

To slope was to welsh, do a midnight flit, sneak away without settling your debts or after you'd stolen something. There was a child's song about it:

I had a sloping lodger, but I don't care,

But I don't care,

He left a pair of clogs that I can wear,

And he won't get them back till he pays me.

Sloping was probably the major navvy-crime against another navvy, and it was never all that widespread (It didn't pay to slope a lodge, any road. You never knew when you'd meet up with them again) though there were a few sloping black-spots, like Breary Bank near the Leighton dam outside Masham, a slopers' haunt right [25/26] up to the Great War, as far as the Mission was concerned. The pay office was beyond the huts, so slopers could collect their pay and slink away unnoticed.

Mrs Garnett particularly scorned slopers. 'Slopers are street corner boys, and such like, who come on Public Works and call themselves "navvies". They are not navvies, but moochers and have no business working with decent men, and bringing disgrace on our respectable class. I wish every one was back and starving where they came from.' (Though she conceded shopkeepers deserved to be cheated for overcharging.)

Some words stayed. Others went. Yorks — strings tied around the leg below the knee to hitch trouser bottoms clear of muck — were known to railway navvies in the 1840S and dam navvies in the 1930S. 'A randy is a drunk frolic,' Thomas Jenour, missionary on the Croydon-Epsom railway, told the 1846 Committee. He added:

'There's every sort of abomination, lewdness and bad women.' As a word it survived into the twentieth century, but only just. As a concept it slowly died away as the navvy settlements were slowly tamed.

[What Navvies Wore]

What happened to navvying in fact was one long taming. Even dress got less flamboyant, more dowdy. Except that they wore knee-breeches we don't know how the first canal diggers dressed, but by the early railway period you could always tell a navvy by the brightly coloured clothes he wore: scarlet waistcoats, glowing neckerchiefs, velveteen coats, white felt hats with the brims turned up, breeches buttoned at the knees, high-laced boots.

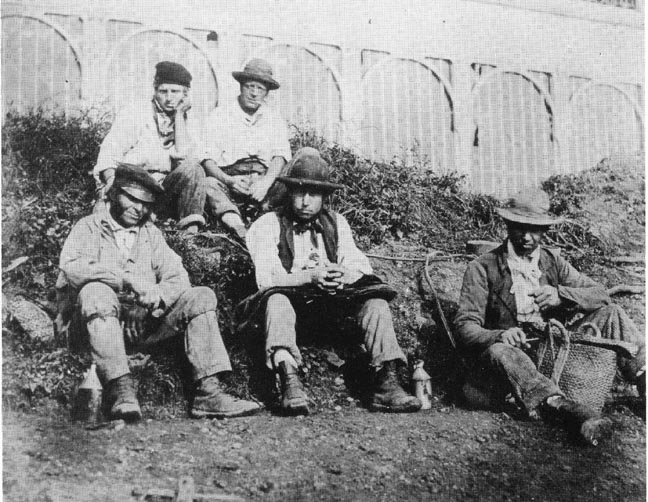

Left: Navvies at mid-century; Middle: Navvies, 1880s; Right: Navvies, 1890s

Click on thumbnails for larger images.

By mid-century, in the '50s and '60s, they turned out on knock-off days all a-dazzle in yellow and blue, scarlet and flame, waistcoats flashing with glass buttons, shining with mother of pearl, rich with silver watch chains. White duck frocks set off blazing silk neckerchiefs knotted sailor-like around muscle-thick throats. Below the waist they were more sombre: short, smooth, velvety moleskin trousers and huge boots. Whiskers, like explosions of hair, exploded from jaws. Thick curls tendrilled about heads gleaming with white enamelled teeth, better than anything in the mouths of those tiresome Italian ruffians you kept reading about.

In 1907 Mrs Garnett remembered the navvies at the Junction dam thirty years ago. [Now one of four lying in line astern near the headwaters of the Tame in the Lancashire moors. Both the village of Denshaw and the dam were called the Junction because five roads cross there. More properly it is the New Year's Bridge dam.] They were dressed in white knee-breeches, blue woollen stockings, thick boots, white shirts and sweating caps. Every Class on Public Works then wore its own dress. The [26/27] Gangers: brown velvet jackets and vests, and cord breeches tucked into high boots. The Black Gang had shining buttons, stamped with engines, on their caps. The (horse) drivers, in red or blue plush waistcoats, with big rows of pearl buttons. The men, double canvas coats, as well as trousers, white all over, and exquisitely clean from top to toe of an evening, a bright neckerchief tied in a knot-silk on Sundays, cotton on work days. In the south of England the men wore much embroidered slops, and frequently these and even shirts were made by the men. It was the fashion in some places to sew pearl buttons on slops, and I have been told of six dozen sewn on one!'

Knee-breeches survived into the 1890s, usually accompanied by thick blue woollen stockings. Double-breasted waistcoats were now popular, along with smocks like big bags. Moleskin, always navvy-fashionable, was worn right into the 1900s when corduroy started rivalling it. Between the Wars, corduroy was the mark of the navvy, as fur is the mark of the beast. Only navvies wore it. Navvies wore corduroy almost as soldiers wore khaki or nannies wore starched cotton: as a uniform. Subdued flannel shirts, bought by post from Wales, latter-day navvies wore as well. By now the navvies' former colour-splashed brightness was reduced to the blue, white-spotted snow-storm neckerchiefs they wore around their necks.

Most navvies in the twentieth century bought their clothes by mail-order from George Key's, the navvy's tailor, in Rugeley. (Old George fell out of a window and killed himself soon after the Great War.) Key's also tailored special corduroy trousers called Forkstrongs. 'When navvies meet and talk of clothes,' ran one of their ads. in the 1920s, 'they are sure to mention Keys' cord trousers. Their fathers thirty years ago nicknamed them "Forkstrongs" because they couldn't split the Forks no matter how hard they wear.'

There was no real navvy-lore as such, just twists on old country wisdom. 'It won't rain if there's enough blue in the sky to make a navvy a waistcoat' (instead of a sailor a pair of trousers). Irish navvies in Brunei's Rotherhithe tunnel believed that if you blinded flood water by dowsing the lights it couldn't see you to drown you. Navvies on the Calder Navigation chipped away Robin Hood's gravestone at Kirklees, thinking it cured toothache. [27/28]

But navvies always expected each other to be cool in danger. Being phlegmatic — 'taking misfortune in your stride' — was part of the navvy ethic. Muck from Blisworth, a thatched, two-tone ironstone village (two tones of brown: light and deep), on the London-Birmingham was wagoned to the Wolverton embankment for tipping. At yo-ho and snap time men and nippers rode the wagons back to camp. Derailments were common. One derailment heaped a body of men and lads under a pile of wagons and limestone. A nipper was dragged from under it, his foot squeezed into a mess of flesh and splintered bone.

'Crying'll do thee no good, lad,' said the ganger, taking his pipe from his mouth. 'Thou'dst better have it cut off above the knee.'

A broken-armed man scrabbled from the same heap. 'It's broke,' he announced, unemotionally, wagging his dangling limb. 'I maun go home.' And home he went, striding the six miles to his village.

A rock fall in a tunnel east of Rouen in the 1840s trapped a French labourer and a Lancashire navvy. Rescuers sank a shaft to them at the rate of ten feet an hour, a brisk mole's pace. When they were safely back on top the Frenchman wept. The Lancashire man strolled round the lip of the rescue shaft. 'You've been an infernal short time about it,' was his professional and professionally phlegmatic verdict.

A contractor called Bayliss used to tell a story about a tunnel just north of Bugsworth on the Manchester-Ambergate line. One day its mouth caved in, trapping a gang of navvies. 'Well, chaps,' said one to the rest, 'we shall never get out alive, so we may as well go on with our bit while we can.' They worked on, hacking at the rock face in the flickering candle light, until one by one they fell limp and dying in the heavy, oxygen-drained air. Rescuers reached them as their candles were guttering. (But there is no tunnel just north of Bugsworth.)

Late in the 1880s one of the shafts of the Cowburn tunnel, opening into the Vale of Edale in Derbyshire, was nine hundred feet deep. Signals to the> banksman were sent by thwacking the iron skips with iron bars [The banksman drove the winding gear.]. One day a skip was dangling just above the floor, with a man inside, waiting for the shot-firer to clamber aboard. The waiting man slipped and struck his iron-shod heel against the skip which was immediately raised. The shot-firer leaped for the rising bucket and was still swinging outside it as the hots went off in a flower-like pattern below him.

Another time a navvy on the Central Railway in Scotland lit his fuses at the bottom of a shaft. As he was being raised in the skip, the winding horse fell down with the staggers. The fuses spat and flared in the blackness a few feet below. Faced with being boinged to death like a clapper in a bell or ripped to bits at the bottom of the pit, the navvy vaulted from the skip and calmly began finger-and-thumbing the fuses. The last was a few micro-seconds away from exploding the gunpowder when he finally snuffed it out.

What humour survives is mainly about the two big facts of navvy life: its hardness and its isolation.

Life was so hard even the softness of a bed could kill. A workhouse bed was soft enough to do for Tommy the Gate in the 1870s. Tommy had been born in a Pickford's van and so was on the move even at the moment of his birth. After failing as a pig-dealer he took to following the navvy camps and never slept in a bed for twenty years until he went into the workhouse where the straw-based softness of his donkey's breakfast mattress butchered him.

In the twentieth century, two bedless navvies one night conrided to a publican that they hadn't slept in a bed for twenty years. The landlord, a jovial soul, gave them a double bed for the night. So delighted were they by its womb-like warmth and flock comfort, they laughed themselves to death.

Getting the better of the non-navvy enemy was a common theme, like the story of the young man who bested a bragging publican's wife on the London-Birmingham in the i83os. She despised all navvies and boasted none would ever outwit her. One morning a young navvy went into her pub, the Stag and Pheasant at Hillmorton on the Grand Union Canal, carrying a gallon stoneware bottle of the kind they called a greyneck. He called for a half-gallon of gin. The landlady poured it into his stone bottle. He refused to pay. She poured the gin back into her cask. Exit the navvy grinning happily. Before going in he'd half-filled the greyneck with water.

A man on the Manchester Ship Canal told a missionary to go to hell. He'd be sacked if he didn't apologise, he was told. The navvy knocked at the missionary's door. 'Are you the man who I told to [29/30] go to hell this morning?' he asked the black-suited man who answered. 'I am. Come in, my poor brother.'

'No,' said the navvy. 'I only came to tell you you needn't go now.' (That at least was the story as told by the Navvy's Guide. Reality was perhaps less flattering. It was at the time of the Canal's financial and labour troubles in 1891. Sir Joseph Lee, company deputy chairman, questioned a navvy about his pay, hours and where he worked. 'Go to hell,' said the navvy. A ganger advised him to apologise. 'Master,' then said the navvy, 'I didn't know who you were, and I told you to go to hell, and I'm sorry for it, but I didn't mean you to go.')

For a time in the early 1890s the Navvies' Union had its own stand-up comic called Brighton Ted to keep meetings amused, particularly along the Manchester Ship Canal. A navvy wrote home to his mother, went one of his jokes. He wrote three big-lettered words to the page. She was a very deaf old lady, explained a nipper, and needed a loud letter.

A temperance man collared a Ship Canal wagon filler. 'Ah, my friend,' said he, 'you shouldn't drink whisky. Whisky's killed thousands. Why don't you drink water? Water never killed anyone.'

'Who are you gammoning?' replied the wagon filler. 'What price Noah's Flood?'

A nipper, mooching from a man who had religion, was given a crust of bread. 'Let us say the Lord's prayer together,' said the godly man. 'The first words are "Our Father".'

'That means my Father as well as yours?' asked the nipper.

'Yes. Everybody's Father, for we are all brothers and sisters in this world.'

'Then you're my brother?' said the nipper, wanting to get it right.

'Yes.'

'Then you ought to be precious well ashamed of yourself,' came back the boy, 'to offer your poor little brother such a hard, dry crust as this.'

In the market square in Lancaster a Salvationist told a navvy to stop smoking. 'Friend,' said the Salvationist, 'If Providence had intended thee for that dirty habit of tobacco-smoking, heaven would have provided thee with a funnel on the top of thy head to [30/31] carry the fumes away.'

'And, friend,' returned the navvy, 'if Providence had intended thee to lead thy murdering brass band by walking backwards, heaven would have had thy toes where thy heels are.'

A notable navvy was being buried. Six men carried him to his grave. 'Reverse the corpse/ said the parson.

'What's he say?' said the unlettered navvies.

The ganger said: 'Slew the old bugger round.' And they slewed him round quick.

A navvy woman took her son to the surgery. 'H'm, costive bound,' diagnosed the doctor.

'Eh, I don't care if it costs five pound,' said the indignant navvy woman. 'The lad's got to shit.'

But then a navvy and his money needed no prising apan. Navvies, like horseplayers, usually died broke, their money dribbled away on drink or gambling even before it was earned. If it wasn't for the beer shop, a navvy told the Rev Sargent in Penrith in the early 1840s, he wouldn't know what to do with his money. He would rather spend it on himself now than let strangers spend it for him when he was dead.

'Wouldn't your wife like a new gown?' asked the parson.

Slowly the navvy shook his grizzled head. 'She's as many as she can use as long as she lives,' he said.

One navvy in the 1880s even professed he thought it was 'the duty and the custom of every navvy to work for his money like a horse and spend it like an ass.' And perhaps on the whole he was right. When life is generally rather short and usually very nasty you can afford to be extravagant with it. Like the old-time lower-deck sailor they had little to lose by burning short candles at both ends. Things were done gargantuanly: living, starving, the hard times, dying.

In 1801 a gang of navvies on the Dearne and Dove canal were given supper in the Red Lion in Worsbrough to celebrate the Peace of Amiens. 'They ate and drank as follows,' reported the Doncaster Gazette, '40 Ibs of beef, 36 Ibs of potatoes, 20 Ibs of pudding, 18 Ibs of bread, and a quantity of ale equal to 150 Ibs weight, which amounted to 10^ Ibs to each man.' (In fact, eleven pounds per man.) John Ward always said a navvy could eat a pound and a half of prime rump steak without being too conscious of having done so. [31/32] Men commonly swallowed two pounds of red meat, two pounds of bread and ten pints of ale in working hours. One man once drank twenty-eight pints of beer in an afternoon.

Jubilee Day, 1897, was a paid holiday for the Elan Valley navvies. Crowds of them, ribald and raucous, trooped down to the junketings in Rhayader, where in less than an hour they gobbled all the food the Jubilee Committee had laid on for the whole day.

Half a gallon of good cheap ale and two pounds of slab-sided beef always induced deep navvy contentment. Collective navvy opinion considered the Westmorland of the 185 os not even part of England on account of the poor thin cow-meat (as opposed to fat bullock beef) and the beer which was very dear at threepence a pint.

Most navvies smoked hugely too: men, women, lasses, nippers, it made no odds. Tobacco was taken in clay pipes called gum-buckets.

In the 1850s Thomas Payers, the missionary on the Lune valley line at the corner of Westmorland, Lancashire and Yorkshire, had a theory about women gum-bucketeers. The long-stemmed smokers were better, neater, tidier housewives than short-stemmed women. Long-piped woman sat more alertly (even bolt upright), cupping the elbow of the arm that held the pipe in their other hand. Short-stemmed sluts sat scrunched up, elbow on knees, shortening the gap between pipe bowl and lazy hand.

One woman had a worn face, dark with grime. She was bleary eyed and lank haired, a long-boned woman, loose-limbed like a broken marionette. The stitching of her frock was so badly stretched it seemed it would pull apart at any moment and her dress would drop in a heap from her gangling bones. She smoked a two-inch stump of gum-bucket. "Tis the only comfort I've got,' she told Payers, taking the ruined black stem from her mouth as she slovened among the ruins of her hut under the rainy fells. 'When I'se upset, and things go 'wry, I get me a pipe, and sets me down, and forgits it all.' [32/33]

Sources

[Note: Full citations for works cited by the name of the author or a short title can be found in the bibliography.]

The names navvies had for themselves is from the Quarterly Letter to Navvies [hereafter cited as NL], Palk, and word of mouth.

Nicknames are from Smiles, Favers, Barrett, Our Navvies, Our Iron Roads, Death or Life, NL, and word of mouth. Nippers' tea making habits are from Kennedy. Mrs Garnett's scorn of slopers is from NL.

How navvies dressed in the 1830's is from Smiles's Stephensons, in the 185 os from Illustrated London News, at Winchmore Hill from Henrietta Cresswell, and at Lindley from Our Navvies. Mrs Garnett reminisced about navvy dress in NL 177, September 1907. The Forkstrong ad. is from the Journal of the National Union of Gasworkers, 1923.

Stoicism at Cowburn is from High Peak: Places and Faces, by Keith Warrender (published by the author). The story of the horse that fell with the staggers was told to the 1846 Committee. Other stoicism stories are from Our Iron Roads, as is the story of the greyneck, the navvy, and the landlady (a different account appears in Lecount).

Most of the jokes are from the Navvy's Guide. The other side of the story of the navvy who told the boss to go to hell is from Leech.

The man who told the Rev Sargent his wife had gowns enough for life is from the 1846 Committee. The man who thought it a navvy's duty to spend like an ass is from NL 30, December 1885.

The story of the Dearne and Dove feast is from Hadfield's Canals where the source is given as the Doncaster Gazette 13 Nov 1801. The Elan valley feast is from the Montgomery and Radnor Echo. Navvy opinion of Westmorland and navvy smoking habits are from Payers.

Last modified 19 April 2006