The first image here is of the front cover of the book under review. The other two are from our own website. Click on the thumbnails for larger pictures and more information about them.

Poor Napoleon! He may have been a towering figure on the world stage, yet in the battle of the bed he had to accept defeat. How could this be? Suffice it to say that when Joséphine's pug Fortune finally met his nemesis, it was his mistress who shed bitter tears, and not his master. Told with a light touch but also with reference to several biographies of Napoleon and his published letters, Mimi Matthews's account of this episode is the perfect curtain-raiser to her book about close encounters with animals in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

As the first and longest section of the book shows, the roles of pet dogs in the household could not be over-estimated. The poet Alexander Pope, for instance, for all his diminutive size and frailty, was the proud possessor of a series of Great Danes called Bounce. Far from knocking him over, they protected him, and were a comfort and inspiration to him in what was undoubtedly a difficult life. His last lines of poetry were on the death of his last Bounce, and Matthews suggests that his sorrow over this loss may have hastened his own death, which occurred soon afterwards. Other authors' dogs featured in the book are Byron's Newfoundland, Boatswain, beside whom the poet had hoped to be buried, and Emily Brontë's devoted bulldog, Keeper, who once bore the full brunt of his mistress's anger without complaint.

Cats were less popular pets in these centuries, but Matthews finds an example of a much-loved one in Dr Johnson's Hodge — "a very fine cat, a very fine cat indeed," as Johnson himself put it (qtd. p. 69). Cat-fanciers remained thin on the ground until the well-known illustrator and obsessive pet-keeper, Harrison Weir, organised the first cat-show at Crystal Palace in 1871. Although the tide began to turn in their favour, there was still an unfortunate association between cats and "maiden ladies" — no doubt encouraged by such cases as that of the "cat hoarding spinsters" (p. 87) reported in Chapter 12. Delving into an array of archival sources here, Matthews gives some intriguing insights into nineteenth-century life and attitudes, and brings out the growing concern for animal welfare towards the end of the period.

Barnaby Rudge and Grip the Raven (1888), by Felix O. C. Darley.

The later sections of the book deal with a whole range of other creatures, from horses and farm animals, birds (including Dickens's two ravens, both called Grip), rabbits and rodents, reptiles and fish to more unusual pets like foxes. Some of them are seen in very curious circumstances which bring these centuries to life more effectively than any textbook. What chance would the "Piccadilly goat" stand on London's congested streets now? What twenty-first century balloonist would risk the wrath of the RSPCA and general public by making an ascent on a pony? And would it still be quite as dangerous to adopt a fox?

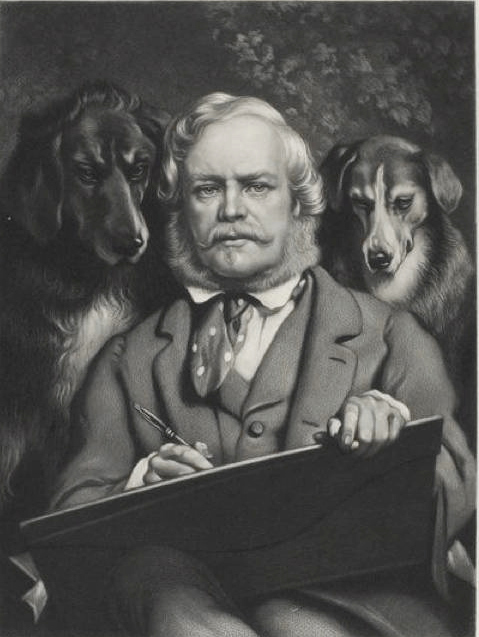

Landseer and His Connoisseurs, self-portrait by Sir Edwin Landseer, pre-1885.

Finally, one of the joys of this book is its large number of very superior colour illustrations. Writers could immortalise their four-footed friends in words: Pope even made Bounce a speaker in one of poems. But others staked their pets' claims to immortality in a different way, by having their portraits painted. Some were so keen to do justice to them that they engaged well-known artists like Thomas Gainsborough, George Stubbs and Sir Edwin Landseer. On display in the first section, for instance, is Landseer's painting of Prince Albert's patient greyhound Eos (1841), commissioned by Queen Victoria as a present for her husband; and rearing up at the beginning of the section on horses and farm animals is Stubbs's magnificent likeness of the Marquess of Rockingham's racehorse, Whistlejacket (1762). Such reproductions, as well as some engravings from the archives, enrich the text tremendously. The paintings themselves become more enjoyable when their backgrounds are fully appreciated.

There are many other heartwarming or quirky stories in this wide-ranging book, and every reader is sure to find some surprises here. They will also find the author's own sympathetic and sometimes humorous reflections — and, once they have finished the last chapter, endnotes and a bibliography to help them follow up their particular interests. The Pug Who Bit Napoleon is due to be published at the end of November this year (2017). But beware: those who buy it as a Christmas gift may feel quite unable to part with it!

Related Materials

Book under review

Matthews, Mimi. The Pug Who Bit Napoleon: Animal Tales of the 18th and 19th Centuries. Barnsley, S. Yorks.: Pen & Sword History, 2017. 177 + ix pp. £14.99. ISBN 978-1526-705006.

Created 5 November 2017