Many thanks to the National Portrait Gallery, London, for permitting us to download the images here. Click on the images to enlarge them, and mouse over the bulleted text for links — Jacqueline Banerjee.

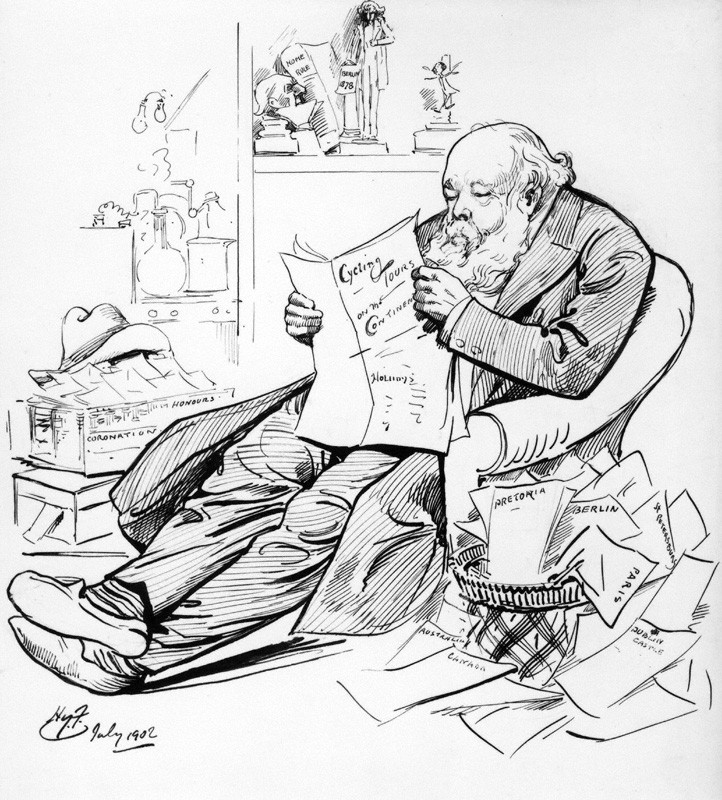

Two pen-and-ink drawings of the third Marquess of Salisbury (1830-1903) by illustrator Henry Furniss. Both © The National Gallery, London. Left: in 1891, NPG 3411; right, in 1902, NPG 3603. Click on images to enlarge them.

- Salisbury's view of flattery: "Cecil had a weak stomach for compliments, which he considered "discreditable to the utterer and odious to the receiver" (66).

- Salisbury's naming of a new kind of holiday:

...in the session of 1871 when a General Holiday Bill came before the House of Lords to add Easter Monday, Whit Monday and the first Monday of August to the two existing national holidays of Good Friday and Christmas Day. Salisbury, never given to Utopian redistribution schemes for working-class advancement but always receptive to ideas that might genuinely ease their lot, fought for it in committee against governmental scepticism, suggesting that they be renamed "Bank Holidays." [126]

- Salisbury warning about experts (as Secretary of State for India, to Lytton, the Viceroy):

I think that you listen too much to the soldiers. No lesson seems to be so deeply inculcated by the experience of life as that you should never trust experts. If you believe the doctors, nothing is wholesome: if you believe the theologians, nothing is innocent: if you believe the soldiers, nothing is safe. They all require to have their strong wine diluted by a very large admixture of common sense. [218]

- Andrew Roberts on Salisbury's "phrase-making," and on phrase-making generally: "Drawing on his journalistic experience, Salisbury was an inveterate phrase-maker, experiencing all the pitfalls of that small, clever but accident-prone band" (247).

- Roberts on Salisbury's dislike of bureaucracy:

As well as an ideological preference for liberty on its own merits, Salisbury was convinced of the inherent incompetence of bureaucracy in general and in particular the way that Whitehall "will create business for itself as surely as a new railway will create traffic." ... His two worst bugbears were the Treasury and the Service departments. The officials of the former he described as "imbecile punctilios." ...He particularly hated its cheese-paring nature and "the damage to England's reputation" which "this unscrupulous straining after minute economy has caused." [281]

- Salisbury as a True Tory:

As Lord Rosebery later pointed out, the Conservatives had at last got a genuine Tory for a leader. Canning had been repudiated by the Tories, Wellington was entirely unideological, Peel was excommunicated by them, Derby had been a Whig Minister and Disraeli had spoken in favour of Chartism in his early career. Here, by contrast and at long last, was a true believer in philosophical and practical Toryism, someone who since his schooldays had declared himself "an illiberal Tory." [334]

- On Salisbury's letters, "No less a master of the English language than Lord Randolph's son paid tribute to the quality of Salisbury's letters, saying they:

have a character and interest apart from and even superior to the events with which they deal. A wit at once shrewd and genial, an insight into human nature penetratingly comprehensive, rather cynical, a vast knowledge of affairs, the quick thoughts of a moody, fertile mind, expressed in language that always presents a spice and flavour of its own, are qualities which must exert an attraction upon a generation to whom the politics of the "85 Government will be dust." [377]

- Salisbury on Ireland, in an 1883 article: "Possession of Ireland is our peculiar punishment, our unique affliction, among the family of nations. What crime have we committed, with what particular vice is our national character chargeable, that this chastisement should have befallen us?" (442).

- Salisbury on a House of Lords debate: "'A Quaker jollification, a French horse-race, a Presbyterian psalm, all are lively and exciting compared to an ordinary debate in the House of Lords,' he wrote, likening them to"'a debate in one of Madame Tussaud's showrooms'" (494).

- A wife's remedy for all ills: "Lady Salisbury also believed in alcohol's medicinal properties; she would administer a medication to elderly tenants at Hatfield made up of the family's left-over medicines all mixed together in a jug, added to an equal measure of her husband's port" (502).

- Salisbury's independent spirit: "Salisbury made British foreign policy entirely by himself, helpfully inured by his peerage from the clamour of the Commons. For even a senior official at the Foreign Office to offer unsolicited political advice, Salisbury regarded as something of an impertinence…..'Until my own mind is made up,' he told his daughter, 'I find the intrusion of other men's thoughts merely worrying'" (511).

- Roberts on Salisbury's cabinet: "The 1895 Cabinet.... had a radically different social composition, with only eight upper-class members and eleven from the middle class, against the ten upper to five middle-class mix of nine years earlier" (604).

- Roberts on Salisbury's dislike of Jingoism:

Within a few months he had identified the Jingoism which the two Jubilees, especially the last, had unleashed, as a serious political problem. He saw the strident support for the expansion of the Empire, "wider still and wider" in Arthur Benson's later phrase, regardless of any other diplomatic or strategic considerations as noble Imperialism's bastard brother, and the bane of his foreign policy. Imperial chauvinism, my empire right or wrong, struck him as a form of insanity, and he used to complain to his officials during Jingoistic outbreaks that it was like having "a huge lunatic asylum at one's back." [666]

- Salisbury on awarding "gongs": "He was delighted when deaths ... released KCBs for his disposal, something he complained never happened regularly enough. The Order of the Bath was, he declared, 'a positive elixir of life – a prophylactic against influenza and all other epidemics. Nobody dies who is either KCB or CB. I shall bring it under the notice of the hospitals'" (671).

- Salisbury on marriage: "Salisbury wrote to Knutsford in January 1891 that: 'The lady question is always a difficult one. Men who have made themselves, have rarely taken the trouble to make their wives at the same time'" (675).

- Salisbury's distrust of political theorists:

"In men of genius, as a rule, the imagination or the passions are too strongly developed to suffer them to reach the highest standard of practical statesmanship,'" wrote Salisbury in his Quarterly Review essay on his hero Castlereagh. "They follow some poetical ideal, they are under the spell of some fascinating chapter of past history, they are the slaves of some talismanic phrase which their generation has taken up, or they have made for themselves a system to which all men and all systems must be bent..... When great men get drunk with a theory," he wrote about political theorists, "it is the little men who have the headache." [838]

Related Material

- A Review of Andrew Roberts' Salisbury, Victorian Titan

- Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (1830-1903)

Bibliography

Roberts, Andrew. Salisbury, Victorian Titan. 1st ed. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1999.

Last modified 28 January 2015