Carved tympanum on a perimeter building at Coram's Fields. The design comes from Hogarth's arms for the Hospital, with the shield showing an infant under the moon and stars. On either side are supporters: on the left, the many-breasted Diana of Ephesus, representing Charity; on the right, the familiar Britannia. Above the shield is the Lamb of God, and below it the motto, the simple statement-cum-appeal, "Help" (see Wagner 184).

The Earliest Years

The children's earliest years must often have been their happiest. First, they were sent away to be wet-nursed in the countryside, with the upper-class female patrons of the Hospital playing "a crucial role" by monitoring their nurses carefully (Zunshine 153). From 1756, the restrictions against admitting infected children had been lifted; these were then sent to be dry-nursed rather than wet-nursed (McClure 93). Numbers seem to have remained fairly stable during the Victorian period. In 1868, for example, 63 infants of about four months old were admitted, with altogether 301 in the institution, and 169 in the country (Archer). Five years later, Edward Walford writes that "[w]ithin a distance of twenty miles, in Kent and Surrey, there are always about 200 of these foundlings at nurse" (359). Information at the Metropolitan Archives shows that babies could sometimes be sent further afield as well, "as far away as West Yorkshire or Shropshire" ("Finding Your Foundling," 1).

When they were approaching five, they returned to the strict routine within the Hospital. The transition from family to institutional life was hard. Some years ago, Bessie, an elderly woman interviewed for a well-known over-fifties' magazine, recalled her own experience at the Foundling Hospital in the early twentieth century, remembering that she grew up "among idyllic orchards," until the day her foster mother snipped off a lock of her hair as a keepsake, and delivered her back to the Hospital. "By the end of the next day, they had shaved off her blond curls, taken away her clothes, dressed her in a regulation serge frock, apron and tippet, and hung a tag around her neck with her name engraved on it. Normal family life was over" (Shepherd 91). Other accounts of the little returnees overwhelmed with shock and grief at being abruptly institutionalized are even more heart-rending: "Some describe the group they were admitted with as being completely silent, others remember a room full of naked, crying children" (Shepherd 92).

Happier scenes in front of the building with a tympanum, as twenty-first century children play in sand- and water-trays, with their parents close by, in Coram's Fields.

Hospital Routine

Arrangements and routines after returning to the Hospital were quite harsh. Having painted a grim picture of the older foundlings' day in the eighteenth century, Ruth McClure says that "in the nineteenth century the Hospital saw only minor changes" (249). The By-Laws of 1856 state that from 1 April to 1 October the porter should ring the bell at 6 a.m., and for the rest of the year at 7 a.m. McClure describes the younger children as having lessons with some playtime, saying that, at first, hornbooks were used to teach reading. But by 1836 the Hospital had acquired a library, and by then teaching methods would have improved.

Timetable, 1856 (By-Laws, 35; click to see properly).

The time allocated to teaching had certainly grown. A chart from the 1856 By-Laws shows lessons before breakfast, and then extending from 9.30-12.30 a.m., and from 2.30-5.30 p.m. (34; see later illustration). The word "Employments" is also used in the timetable. In the eighteenth century, the older children did handiwork — sewing and housework for the girls, for example, and rope-making and gardening for the boys. This was not simply for teaching purposes: the work done by the older children earned the Hospital some much-needed extra funds. Like everything else, this was also intended to prepare the children for the kinds of menial roles they were expected to play in later life. Reference to "domestic and other labour" in the ByLaws (29) suggest that these kinds of "employments" continued.

Left: Orphan girls entering the refectory of a hospital, by Frederic Cayley Robinson (1862-1927), 1915. Here, the girls come down into the refectory through an arched staircase, adopted by the artist from Edward Burne-Jones's The Golden Stairs of 1876-80. Courtesy of the Wellcome Museum.

Wearing a uniform reinforced the sense of being institutionalized. Hogarth designed the original uniforms, as well as the Hospital's shield. The clothes were brown, not blue as in Robinson's painting above, but enhanced by scarlet trimmings. The material was hard-wearing drugget at first, not serge — drugget is now associated with floor-covering rather than apparel. At prayer in the chapel, another important part of the daily routine, the girls wore white bonnets and pinafores too, these helping to turn them into the "pooty little things" of Thackeray's "Ballad of Eliza Davis' (160; see Part One). Despite modifications, the uniform was still quaintly old-fashioned in the early twentieth-century, as Bessie's reference to a tippet or shoulder-cape would suggest.

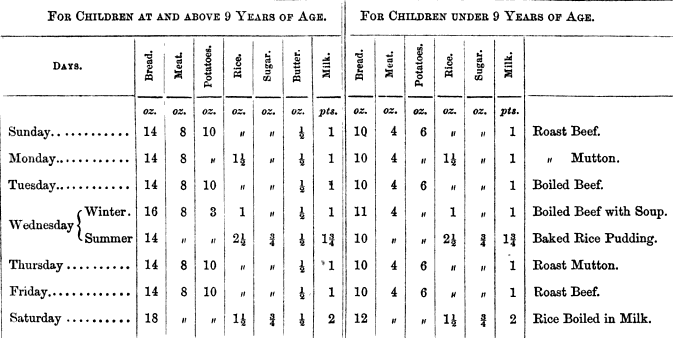

Diet chart (By-Laws, 34; click to see properly).

Life was generally very simple. The children ate plain fare, in the past the uniquitous watery porridge called gruel, and boiled meat, except on Sundays, when they had a roast. Supper was generally bread, with either milk, butter or cheese. In all, it was not dissimilar to the kind of diet provided in the workhouses later on. One feature that McClure picks out as different and rather unusual even in the early diet charts was the inclusion of potatoes. All this had certainly improved by 1856, when the diet chart shows a grand total of four roast meat days (two beef, two mutton), and only two altogether meatless days, one of them in summer alone (By-Laws, 34).

As time went by, the menu like the uniform improved. There is a pleasant picture of the girls and younger children eating quietly in the refectory in "No Thoroughfare," the Christmas story by Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins, with visitors wandering up and down the long room and relieving its monotony with the odd word of kindness (9-10). The children seemed to be on show at this time, as they ate their Sunday roast. However, the visitor finds that the boys' refectory is much less of a draw: "At length she comes to the refectory of the boys. They are so much less popular than the girls that it is bare of visitors when she looks in at the door-way" (11). The account brings home the fact that the children were not only generally isolated in their institutional world, but strictly segregated even within it. Boys were housed in the West Wing, their days passed under the supervision of the schoolmaster and drillmaster. The girls were in the East Wing, and supervised by the Matron, whose duty was "to educate and train the minds of the girls, in such a manner as will make them intelligent, obedient, and teachable servants, when they leave the walls" (By-Laws, 21).

Yet, however pared-down their existence was, however cut off from the outside world and unlike life with a family, living in the Foundling Hospital was still better than living in the workhouse or on the streets (see Part Four). Another (real-life) Victorian visitor to the Hospital described it as a happy place, with a "great jovial kitchen" and two rocking horses in the infant-school. This visitor was pleased with the children’s "general healthy enjoyments, cheerfulness, and unrestrained childishness," and thought they looked much happier than children in other types of homes (Archer). The only problem here is that it had become fashionable both to visit and extol the Hospital. There is something self-congratulatory in the glowing account, which should be set against the description of the children eating silently in separate refectories in "No Thoroughfare."

Looking past the Art Room towards the Band Room at the end, housed in a rebuilt nineteenth-century building in Coram's Fields. The arts are still important on the present-day charity's work.

One change across the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries did help: in 1847 a Boys’ Band was formed (Archer). The musician and musicologist Charles Burney, Fanny Burney's father, had been closely involved with the institution in the eighteenth century, and had had long ago suggested that music should be an important feature of the children's lives. He had even proposed establishing "a national School of Music on the lines of the Conservatories on the Continent" (see Compston 108-9). This had been too much for the governors of the day, who feared the kind of influence this might bring in. The mid-Victorian "Juvenile Band of Musicians" may not have been quite what Burney had in mind, but the more enlightened Victorian governors voted £250 for buying instruments, and appointed a proper bandmaster. It proved to be a "highly successful experiment" (Nichols and Wray 320). A new bandroom was erected in 1864, and the band became a major asset to the Hospital. It was seen to improve the physical capacities of the weaker children, contributing to their social skills, and, perhaps most important of all, enhancing the boys' future prospects.

Apprenticeships

Between the ages of ten and twelve, rising later to fourteen for boys and sixteen for girls, the foundlings were apprenticed to masters outside the Hospital. The governors tried hard to ensure that they understood their rights, and were well treated. Of the first fifty-nine children to be apprenticed from the Foundling Hospital, about half (most of the boys) had followed in Coram’s footsteps, and gone to sea — like him, on trading ships. Now there were more possibilities. Of the boys who showed musical talent, for example, "many, at their own desire, have been placed as musicians in the bands of Her Majesty's Household Troops" (Brownwlow 126). Others went to work for farmers, tailors, bakers and so on. The girls often became housemaids, although some learned skills like embroidery and hat-making: the first girl ever to have been apprenticed had gone to a London silk-dyer (Nichols and Wray 183). Touchingly, many children remained close to the nurses who had cared for them as babies (see Walford 359), and were apprenticed back into their families. These, athough now taken as apprentices, tended to become part of the family again.

A well-known fictional example of a girl taken from the Hospital as a housemaid is Tattycoram in Dickens’s Little Dorrit, serialised from 1855-57. The Meagles family take her after seeing her in the chapel there. While the last part of her name acknowledges her background, "Tatty" has evolved from "Harriet," via "Hatty," and has connotations not only of rags and tatters, but scattiness. Indeed, Tattycoram is headstrong and impatient. But at length she realises that "no people could ever be kinder" to her than the Meagles (20), and comes to love "the dear old name" (614).

Last modified 11 May 2016