Photographs by the author. [Click on images to enlarge them.] You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.

The King's House, Spanish Town.

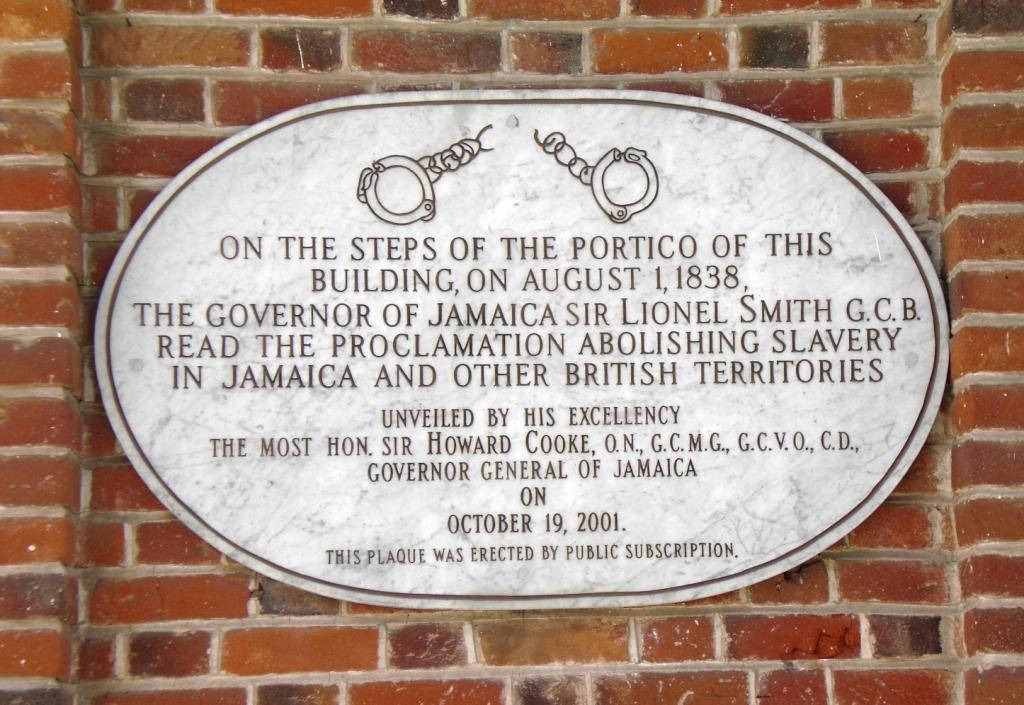

nly one year into the Victorian age, on 1st August 1838, slavery was finally and fully abolished in the British colonies. So ended the single greatest source of shame of Great Britain and its empire. Britain sought to recoup some of its moral deficit by trying to interdict the slave trade elsewhere (in West Africa, Brazil, Cuba and the southern states of the USA) with an admirable tenacity over subsequent decades. But the damage had been done and remains a live issue to this day. British Prime Minister David Cameron’s 2015 visit to Jamaica was overshadowed by the legacy of slavery.

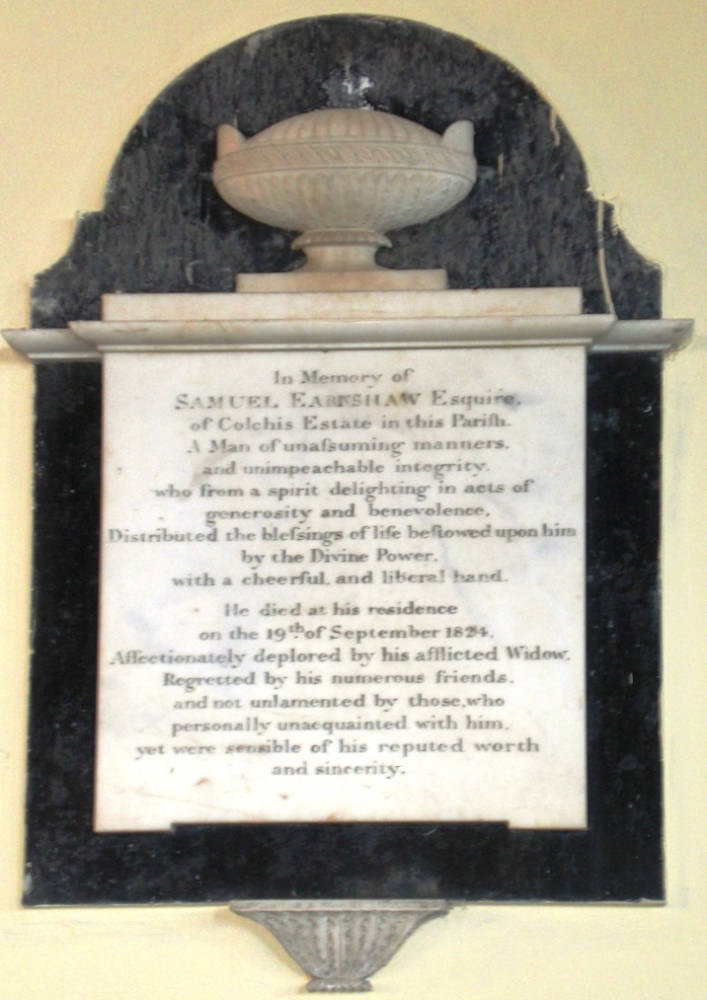

Left: Plaque commemorating the place at which the abolition of slavery was declared. Right: Memorial plaque for a Jamaica slave holder.

Unsurprisingly the abolition of slavery also ended the huge profitability of the plantations of Jamaica and the British Caribbean For the remainder of the Victorian period the region would become something of a colonial backwater. Many of the 700 Great Houses (some of which were really quite small) were abandoned and disappeared into the jungle as did the elaborate sugar factories with their boiling and trash houses, mills and water wheels. Most of the former slaves were happier settling in the hills or on their old provision grounds and living a life of subsistence on the rich agricultural land than working on sugar plantations. Immigrants were brought in from Germany and India to work the estates (not just sugar but coffee and pimento) but Jamaica’s period of economic dominance never recovered.

And what a period of supremacy it had been! As Derrick Knight points out the profits from sugar built many of the most prosperous areas of Georgian Britain; not just the great seaports of Liverpool, Bristol and Glasgow but also the Bloomsbury and Marylebone areas of London and some of the most venerable towns in the shires; Bath, Edinburgh and Cheltenham. Many of the great families of Britain built their fortunes on sugar and slavery. A new study by University College London has demonstrated (by researching the slavery compensation claims paid to owners) that the profits trickled down to middle class families all over Britain; not just bankers and landowners but clergymen and widows. There was also a particular nexus between Jamaica and Scotland, following the failure of the Darien venture as Dobson has shown.

Jamaica was a British colony from 1655 until 1962; making it one of the longest serving parts of the empire. Indeed it straddled what is sometimes called the first empire (up until the surrender of the American colonies following Yorktown) and the second empire (when the focus was mainly on India). Nowadays it is hard to believe that some in Georgian London were willing to sacrifice the American colonies so long as Britain retained the profitable Caribbean islands, in particular Jamaica.

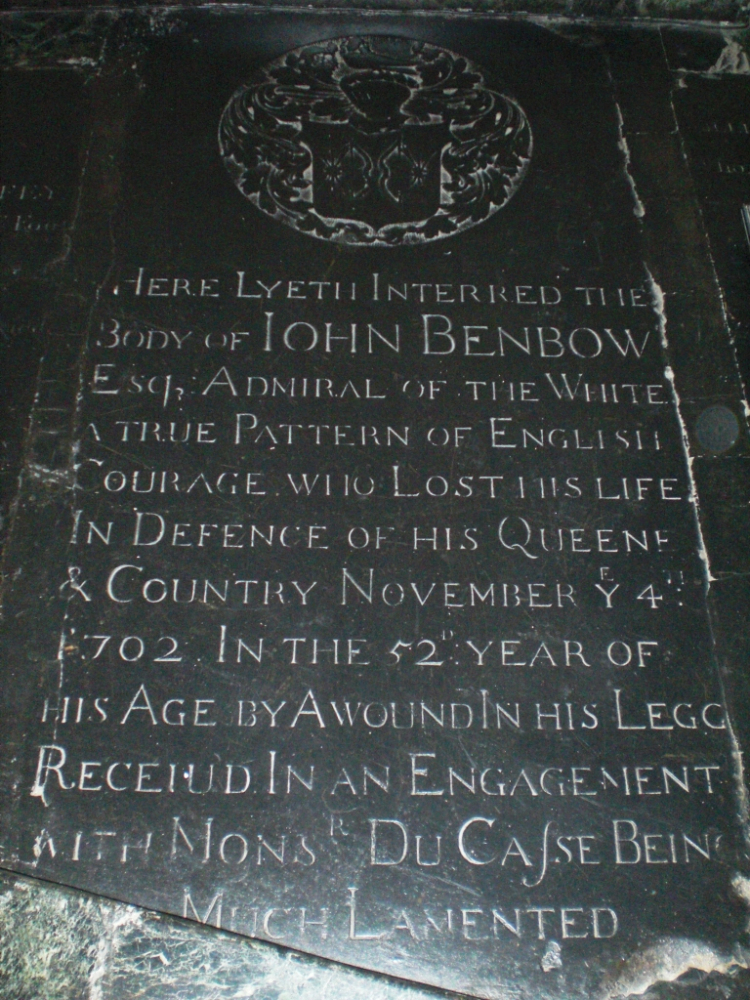

Left: Grave stone of Admiral John Benbow. Right: William Carr Walker's memorial in Lucea.. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Jamaica was also an important naval station from 1675 and throughout the Georgian and Victorian eras until its closure in 1905. The Caribbean had been hotly disputed between Britain and Spain in the 17th Century and between Britain and France (and Spain) in the 18th. Only after Rodney’s victory at the Saintes in 1782 was Britain’s dominance secure although there were serious naval scares before Trafalgar in 1805. Most of Britain’s naval heroes have been based in Jamaica. Admiral Benbow is buried in Kingston parish church (see photo). Nelson too was posted in Port Royal and there is a plaque to him at Fort Charles (photo) with the inscription “You, who tread his footprints, remember his glory”.

Fort Charles, Port Royal. [Plaque commemorating Horatio Nelson]

The army presence was also important; not only to protect the island from invaders but also to reinforce the militia against slave revolts. George Gilchrist writes to his uncle in 1764 “there has been a very great insurrection this year made by the negro slaves, it seems they took it in their head in the Easter holiday and gathered in a body of about 12 hundred before they were the least suspicious of any such thing, they attacked three or four different plantations putting all the white people to death and seizing all the money and arms”. Indeed the worst incident of military retribution against an uprising would happen in the Victorian era when a rebellion in the Morant Bay area was suppressed in 1865 under the orders of Governor Eyre with an excessive use of force. The incident led to a furore in London, the withdrawal of the Governor and his enforced early retirement to Devon. The story is well told in Jan Morris’s Heaven’s Command (pp. 301-317). The white inhabitants lived in daily dread of rebellion, and it was a source of some pride when a planter’s workers protected him and his family from an insurrection as in the case of William Carr Walker at Bamboo plantation (photo).

Left: Greenwood Great House. Right: A colonial house in East Street, Kingston.

In Jamaica and the other British Caribbean islands the wealth of the Georgian period is best seen in the remaining Great Houses like that at Greenwood (photo), the magnificent Town Halls and in the Anglican churches, where no expense was spared on sculptures by John Bacon the elder or Westmacott. Anglicanism was closely associated with the planters and colonial elite whereas the black population preferred the dissenting or non-conformist Methodist and Baptist churches. The great missionary William Knibb was a Baptist. His first words on arrival in Jamaica were “I have now reached the land of sin, disease and death”. His memorial is in the grounds of the Baptist church in Falmouth (below).

Left: Memorial to William Knibb, the Baptist missionary. Right: The Anglican Church in Falmouth. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Indeed the fear of disease and death suffuse many of the writings of the period. Maria Nugent was the young wife of General Nugent, the Governor in the early 1800s. Her remarkable diary of those years is replete with the fear of death from yellow fever and from the pestilential climate. When her children were born her fears were exacerbated; not least because her representational duties involved huge banquets at the King’s House in Spanish Town (photo). It was something of a miracle that she, her husband and children survived as their guests (young naval and army officers, lawyers, officials and planters) died all around them. Maria Nugent escaped to Stony Hill in the foothills of the Blue Mountains when she could or to the sea air of Port Henderson. Most of the Great Houses were built on hill tops where the air was cooler and clearer with wide verandahs to catch any possible breeze. Anthony Trollope was also struck by the unhealthiness of Jamaica during his 1858 visit. But the habits of the British and Creole residents hardly helped. They drank and ate to extraordinary excess.

In spite of the profusion of churches it was also a godless place. George Gilchrist wrote to his uncle in 1764:

I’m at a great loss to find whether or not there is any [religion] in the Island for I have never been at their Church yet and by the appearance of the inhabitants I’m more apt to believe I’m got amongst Heathens than Christians, for at their Sunday meetings (as the gentlemen most commonly visit one another at day) immediately after dinner the company most sing a profane song all round and get drunk and consequently after being drunk quarrelling and fighting but however I’m informed there are a few churches but that their congregations seldom exceed two or three old wives and that their clergymen give more examples of vice than of virtue.

And yet, however ungodly the population might have been, they were keen to adorn the churches with testament to their lives. Some, of course, were undoubtedly honourable men and women. Both Lewis and Hakewill testify to this fact. But overseers generally were not. After all their job was to get the maximum production out of their workforce. William Gilchrist writing to his mother in 1784 says “a tyrannical Overseer makes no distinction between them [young white book-keepers] and the slaves whom it is their chief employment to drive”. However my photo of Samuel Earnshaw’s plaque in Falmouth church hides a truly insidious story. According to an anti-slavery tract of 1830 “A mulatto female slave, Eleanor Mead of Colchis estate in Jamaica. Her owner Mrs Earnshaw, for some offence, ordered her to be stripped naked, held prostrate on the ground and given 58 lashes of the whip. One of the people ordered to hold her down was one of her own children. She was then, still semi naked, put in the stocks with her feet fastened.” Later it emerged that Mrs Earnshaw’s venom was because “Mr. Earnshaw had cohabited with this woman during his lifetime” (Monthly Anti-Slavery Reporter for 1829).

The Rio Cobre bridge today and in Hakewill's watercolor.

In contrast to such horror is the sheer beauty of the island. We are fortunate to have some wonderful images of Jamaica produced by some fine artists. Supreme amongst these is James Hakewill. His 31 “drawings made in 1820 and 1821” are superb. Many of the scenes are recognisable today. I have included “then and now” pictures of the Bog Walk (the road north of Spanish Town) and of the Rio Cobre cast iron bridge at Spanish Town built in 1800 in Rotherham and installed the following year.

Left: Bog Walk. James Hakewill. Right: Bog Walk today. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

It is a wonder that any architecture has survived in Jamaica at all because it has suffered the most incredible natural disasters. Best known is the earthquake of 1692 which sank two thirds of Port Royal into the harbour. But there were major earthquakes in 1812, 1824, 1839, 1907, 1914, 1943 and 1957 and perhaps two dozen major hurricanes including Gilbert in 1988 and the truly epic hurricane of October 1780.

Left: The epic sugar factory at Magotty or Kenilworth.JPG. Right: The remains of Flint River Great House near Lucea. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Jamaica today is an island of contrasts. At Montego Bay and Negril western tourists enjoy their “all inclusive” holidays and have little or no contact with the islanders or its history. It is ironic that one of the few guided tours, of Rose Hall Great House, includes a completely mythical story of cruelty to servants and slaves whereas (as we have seen in the Earnshaw case) there are plenty of real examples. The island is still full of well maintained and well attended churches and yet violent crime and gang culture remain a significant problem. Yet once you leave the beaten track and explore the terrain behind the coast you immediately come across evidence of Jamaica’s eighteenth-century economic power; sugar mills covered in jungle creepers. It is curiously alluring but with an abiding sense of historical discomfort.

Further reading

Black, Clinton. History of Jamaica. Kingston: Longman, 1983.

Dobson, David. Scots in Jamaica. 1655-1855. Baltimore: Clearfield, 2011.

Hakewill, James. A picturesque tour of the island of Jamaica. London: Hurst and Robinson, 1825.

Knight, Derrick. Gentlemen of Fortune. London: Frederick Muller, 1978.

Legacies of British slave ownership. London: UCL Department of History, 2015.

Lewis, Matthew. Journal of a West India Proprietor. Oxford: OUP, 1999.

Monthly Anti-Slavery Reporter January 1829. Supplement to the Religious Intelligence in the Christian Observer for 1829. London: Ellerton and Henderson, 1830.

Morris, James. Heaven’s Command. London: Penguin, 1973.

Trollope, Anthony. The West Indies and the Spanish Main. Gloucester: Alan Sutton, 1985.

The Gilchrist letters. GD153. The Scottish Record Office, Edinburgh.

Wright, Philip. Knibb, “the notorious” London: Sidgwick and Jackson,1973.

Wright, Philip.Lady Nugent’s Journal. Kingston: Institute of Jamaica, 1966.

Yates, Geoffrey. Rose Hall; Death of a Legend. Unpublished, 1965. (Available on the Jamaican Family Search website).

Last modified 29 November 2015