The Crimean War resulted from a string of blunders:

- blunder, misunderstanding and lack of clarity between the Powers consequent

to

- failed diplomacy

- failed co-operation

- suspicion between the Powers which was not controlled

- the itch for a fight after 40 years of peace

- Britain's weakness and indecisiveness

- Stratford's encouragement to the Sultan to resist Russia

- religious reasons, which hid the deeper conflicts and desires of the Powers

- collective blunders, reflecting the changed nature of collective diplomacy in Europe

- a series of changed personalities which led to a lack of expertise in dealing with dangerous situations

- collective responsibility due to a lack of a 'Congress' mentality that had followed the end of the French Wars

- too many conflicting individualisms which allowed 'drifting'

Examples of Britain's war hunger and over-confidence from Punch': A Caution to Imperial Birds of Prey, Right against Wrong, and A little cloud . . . [Click on images to enlarge them and to obtain information about them.]

Britain had little to gain from the war but became involved in order to

- restrain of Russia, rather than protect Turkey

- stop the advance of the Russian Black Sea naval power

- stop the advance of France in Napoleon III's ventures

- preserve her Mediterranean bases and protection of her over-land route to India

- maintain her prestige and continue the advance of British supremacy

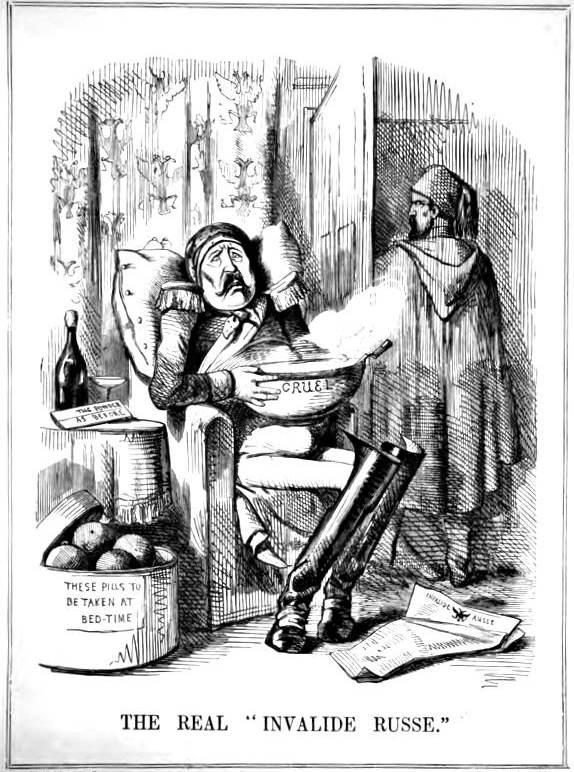

Examples of attitude toward Russia from Punch': St. Nicholas of Russia, The Real “Invalide Russe”, and Montagne Russe — a Very Dangerous Game. [Click on images to enlarge them and to obtain information about them.]

Britain perhaps had more to lose by entering the war because if she lost she would have to accept a peace imposed by Russia. That might include loss of territory, bases and ports, and pose a threat to India. Britain therefore had to be victorious in order to maintain her prestige, empire, the routes to and control of India and her Mediterranean bases. For Britain, the war was very much a gamble with the odds stacked her for a while. Having blundered into the war, Aberdeen's government then failed to conduct it competently. The result was stalemate: it should have been a short war — everyone said that it would be 'over by Christmas' but it dragged on. It was almost a war of honour rather than one of necessity so that Britain could 'teach Russia a lesson'.

The west coast of the Crimean peninsula. This map is taken from Christopher Hibbert's The Destruction of Lord Raglan (Longmans, 1961), p. 10, with the author's kind permission. Copyright, of course, remains with Dr Hibbert. Click on the image for a larger view

There could be no naval action of any significance during this war because Russia was a land power. Britain was therefore unable to use her major force to any effect; and there was no way that Russia would risk a naval engagement because she did not have the sea power. Britain and France knew their armies faced huge difficulties on land against Russia because of the Russians' "scorched earth" policy — no-one knew the devastating effect of this better than the French who had been defeated in 1812 by this policy and the Russian weather. Consequently, the war had to be a coastal fringe campaign; it became bogged down in the Crimean peninsula where neither side could win, but both could reinforce.

The Allies initially went to Varna to ensure that Russia had evacuated Moldavia and Wallachia. By the time they arrived the Russians had almost completed their withdrawal, therefore to teach the Russians a lesson it was decided to take the troops to the Crimea for a quick campaign against Sevastopol, which was to be captured and destroyed. Russia could have been defeated within a few weeks, but was not because of lost opportunities. All the combatants wanted a quick campaign and rapid end, once honour had been seen to be satisfied. Britain and France landed troops at Eupatoria on 14 September 1854. This was not an auspicious day: it was that anniversary of:

- Britain's introduction of the Gregorian calendar in 1752 when there had been riots in the streets and many deaths

- Napoleon's arrival in Moscow in 1812

- Wellington's death in 1852

Troops quickly fell prey to cholera at Varna in the summer of 1854 and were weakened by September. There was also confusion because the British and French had never fought together before: traditionally, they were enemies. The British forces were led by Lord Raglan, aged 66. Raglan had served under Wellington and followed his methods, without his ability. he thought that the French were the enemy at times. He died in the Crimea. The French forces were led by Marshall St. Arnaud, who died in the war and was replaced by Canrobert. There was no overall supreme command and the Commanders-in-Chief found it difficult to co-operate with each other.

The Landing at Eupatoria: William Simpson, The Seat of War in the East, second series. I am grateful to John Sloan for permission to use this image from the Xenophongi web site and which graciously he has agreed to share with the Victorian Web. Copyright, of course, remains with him. Click on the image for a larger view

The target of landing at Eupatoria was Sevastopol - the main Crimean town. They had a march of 100 miles between the two, which could have been taken within a week of their arrival. At this point, the generals showed themselves to be a match for the politicians in incompetence.

- Lord Lucan was in charge of the Heavy Brigade. He was nicknamed "Lord Look-on" by his own men.

- Lord Cardigan led the Light Brigade

These men were brothers-in-law, hated one another and refused to work together.

Furthermore, the Allies were equipped for a short summer campaign. Insufficient supplies were provided and the armies were not equipped for a winter campaign. The Supply Department in Britain had not been reformed since the French Wars and was inadequate to deal with the demands of a war 2,000 miles away. In the British army, the purchase of Commissions still ruled the day, and experienced officers from India were treated as inferior. This meant that inexperienced men who led the army refused to make use of the knowledge of officers who had fought recently.

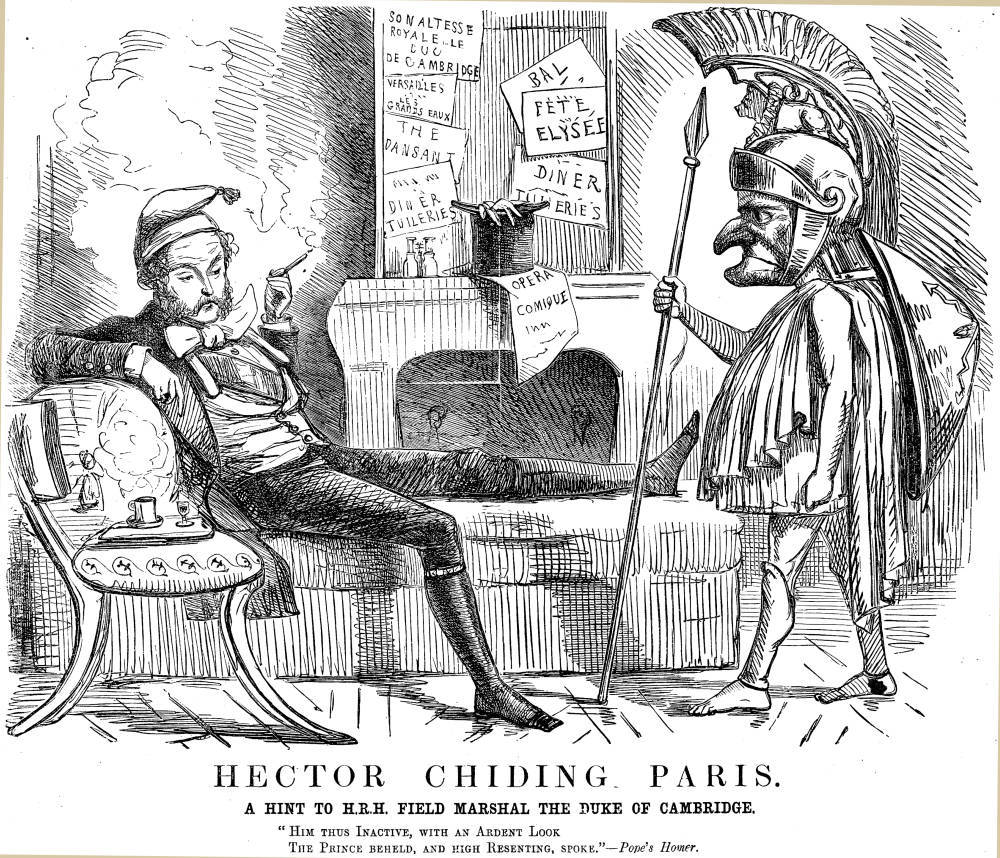

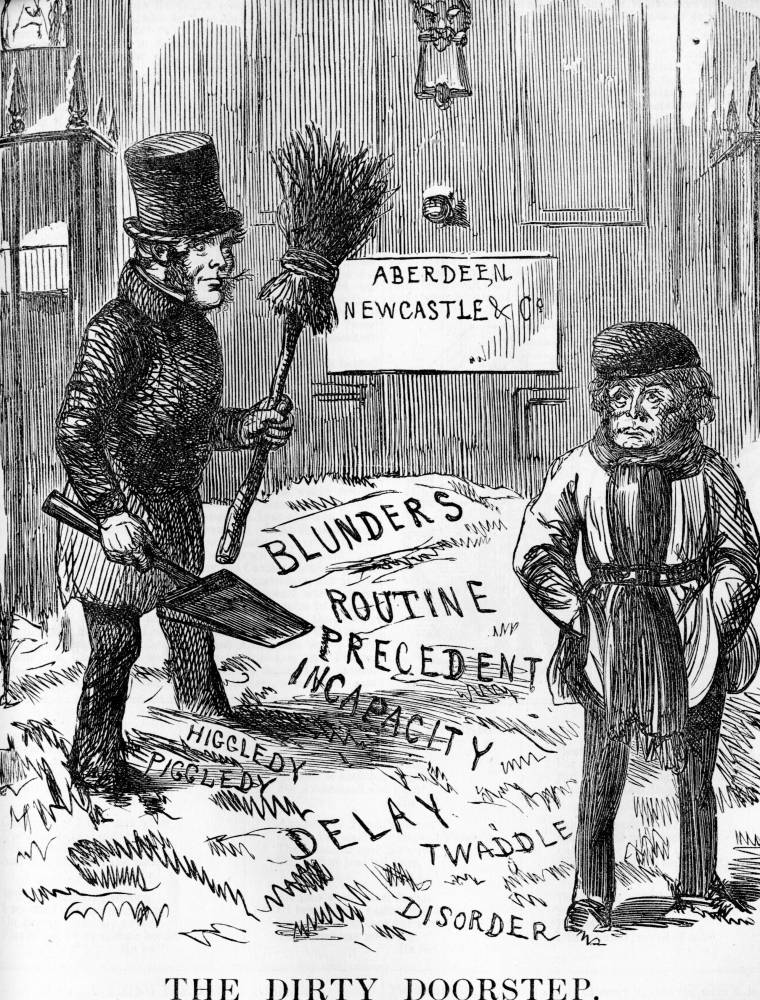

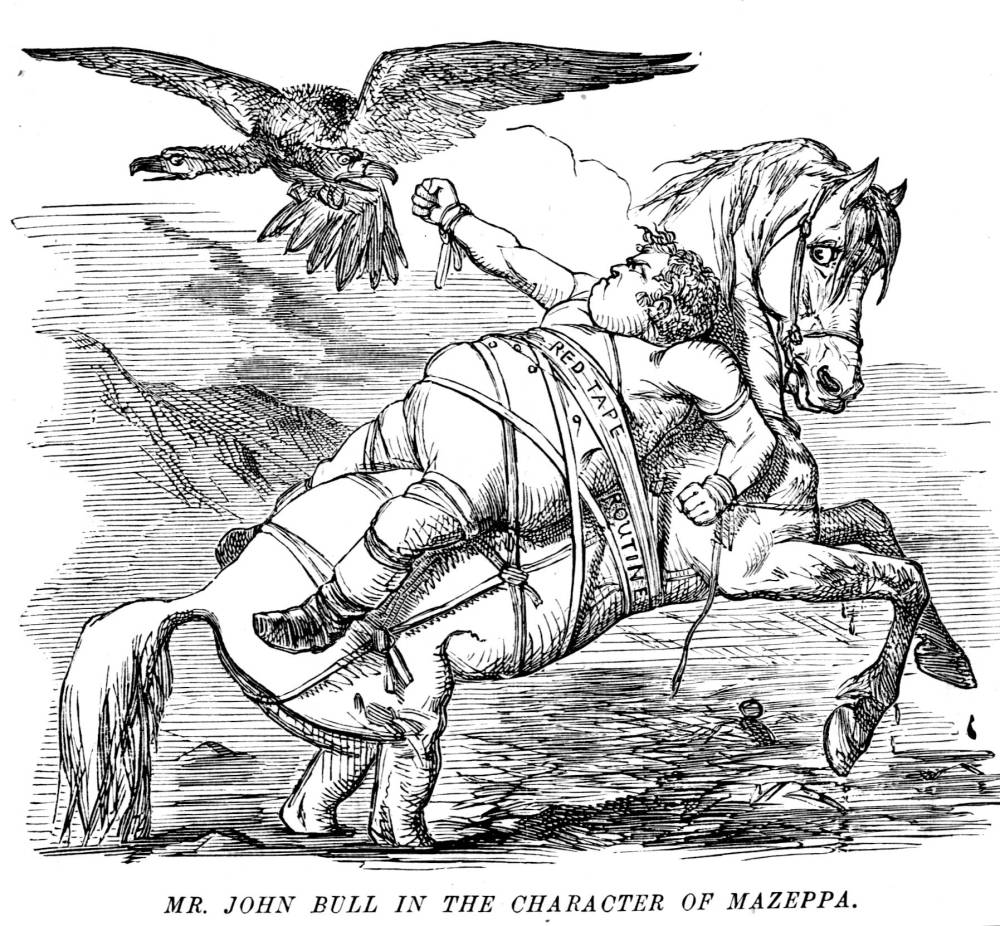

Examples of public anger over military and logistical incompetence and from Punch': Hector Chiding Paris [criticism of the Duke of Cambridge], The Dirty Doorstep, and Mr. John Bull in the Character of Mazeppa. [Click on images to enlarge them and to obtain information about them.]

Last modified 8 May 2002; images added 14 May 2014