Menageries and London Zoo

Polito's Royal Menagerie, Exeter 'Change, Strand. Ackermann's Repository, Plate 2, Vol. VIII (1812), facing p. 27. [Click on this and the following images to enlarge them, and for more information about them where available.]

Helen Cowie talks of the "surprising pervasiveness of exotic animals in nineteenth-century Britain" (2), and indeed those who were unable to keep living and breathing exotic creatures themselves could still go and see them. The two London menageries (at the Tower of London and the Exeter Exchange on the Strand) closed before the beginning of the Victorian era, and their remaining animals were sent to the new Surrey Zoological Gardens — the future London Zoo. Having been granted an irregular plot in the new Regent's Park, this opened to the public in 1847. Despite initial objections to letting people into an area which natural historians considered their own preserve, visitors could now promenade past the structures and enclosures designed by Decimus Burton, admiring and learning something about the animals on their way.

George Du Maurier's At the Zoo for English Society, 1897. The mother here reflects the artist's feeling that the animals, rather than the visitors, are the spectators.

Just as an example, in 1850 the zoo acquired the first live hippopotamus to be seen in Europe. The Times ran a jocular article which it borrowed from Household Words, reporting that the creature drank huge amounts of milk and consumed huge amounts of meal, but was nothing short of a "Benefactor to the whole human race," in that "he bathed and slept serenely for the public gratification," and "[p]eople of all ages and conditions rushed to see him bathe and sleep and feed" (4). In the late Victorian period, a baby hippo was still a star attraction:

But the pride and flower of all the youth of the Zoo is the young hippopotamus. As it lies on its side, with eyes half closed, its square nose like the end of a bolster tilted upwards, its little fat legs stuck out straight at right angles to its body, and its toes turned up like a duck’s, it looks like a gigantic new-born rabbit. It has a pale, petunia-coloured stomach, and the same artistic shade adorns the soles of its feet. It has a double chin, and its eyes, like a bull-calf s, are set on pedestals, and close gently as it goes to sleep with a bland, enormous smile. It cost £500 when quite small, and, to quote the opinion of an eminent grazier, who was looking it over with a professional eye, it still looks like “growing into money.” There are connoisseurs in hippopotamus-breeding who think it almost too beautiful to live. [Cornish 215-16]

People did not need to travel far to see such animals. Supplied by the Jamrach establishment and others (including William Cross in Liverpool, and Hagenbeck's in Hamburg), at least a dozen travelling menageries were touring the country by the 1860s (Tait 70), featuring curiosities like hyenas and jackals as well as lions, tigers and elephants. The appeal of these "transcended social boundaries" (Cowie 3). The best known, throughout the period, was Wombwell's. On 28 October 1847 the Queen recorded the menagerie's visit to Windsor Castle, and enthused in her journal about the fourteen wagon-loads of animals that rolled in, commenting on the "very accomplished elephant" and "a lioness, with 2 dear little cubs."

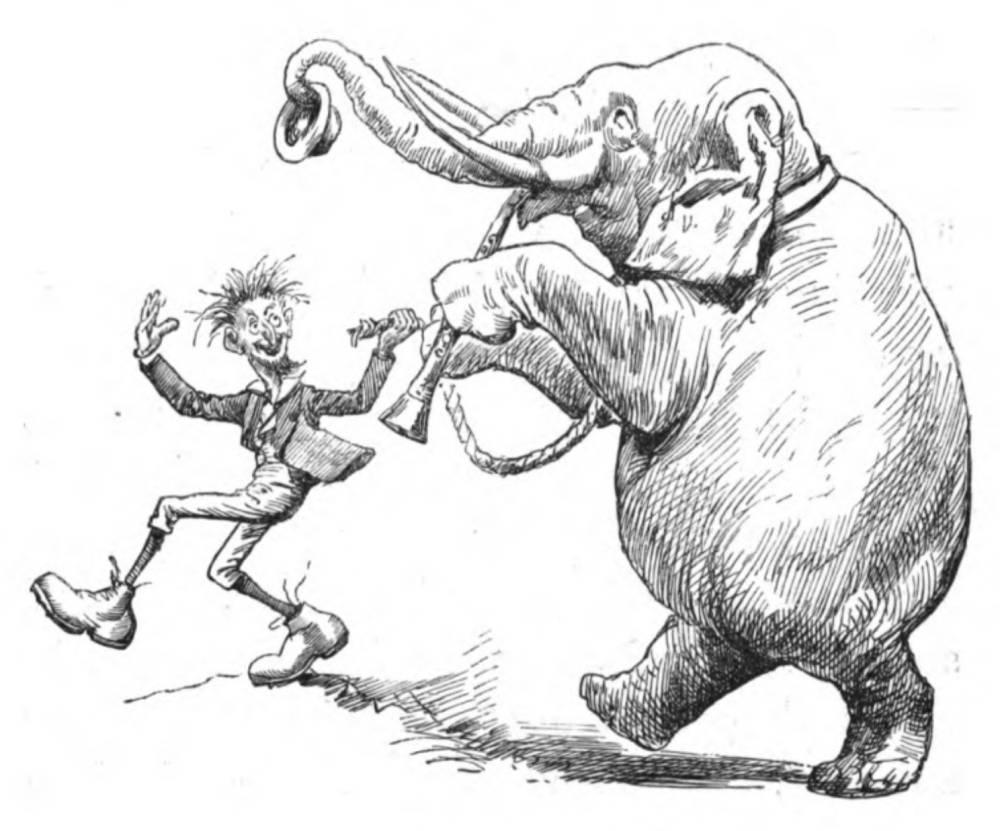

"And in marched an elephant," by Harry Furniss, an illustration for Lewis Carroll's Sylvia and Bruno (1889).

Circuses

Circuses were another place to see exotic animals. With their roots in traditional local fairs (some of which still flourished) and the fabulous riding exploits of performers at Astley's Ampitheatre in London, some circuses still travelled, while some had settled homes in the bigger cities (see Assael 7). Wherever they were, they drew crowds of spectators for their human and animals stars alike. Equestrian displays now jostled with costumed monkeys, trained elephants and "big cats," as well as with the more homely pirouetting dogs, and pigs trained to "count" with their trotters. The appetite for watching exotic animals continued unabated throughout the period, and again drew people of all classes. Caging and taming these imported animals undoubtedly reflected Britain's fascination with its vast overseas empire — and its feeling of superiority over it. Brenda Ayres points out that the constant debate in parliament about the treatment of animals "indicates that neither humane treatment nor the conviction that humane treatment should be shown to animals was universal," and that this reflected the continuing "ambivalence that the Victorians had about animals and what constitutes civilization and superiority" (10).

The Lion Queen. c. 1874. Chromolithograph. Library of Congress, reproduction no. LC-DIG-pga-03215, in the public domain.

Not unexpectedly, like parts of the empire itself, the animals sometimes struck back. Jamrach's Bengal tiger was not the only one to escape and run amok "to the intense terror" of those around ("Frightful Occurrence," 12). Most spectacularly, there were several incidents involving the female lion-tamers, the "Lion-Queens" who were the star turns at these attractions. These performers' very vulnerability was compelling, linked as it was with their feminine attractions, and perhaps also with the transgressive nature of their bravado (see Cowie 188-90). But in January 1850 George Wombwell's own niece, Ellen Bright, was ferociously attacked and killed by a tiger in front of the spectators, and at the trial which followed, the jury "expressed a strong opinion against the practice of allowing persons to perform in a den with animals" (qtd. in Ward, Ch.7). In fact, the Lord Chamberlain intervened to ban women from performing in this way, although men continued to do so for many years afterwards. Whatever the issues raised in parliament, at this point the unnaturalness of the animals' situation, and the constraints they endured, were not the main considerations.

Related Material

- The Victorians and Animals: An Introduction

- Part I: Animals as Part of the Household

- Part III: Studying Animals

- Part IV: Working Animals

- Part V: Animal Rescue

- At Astley's (scene of the audience, by Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz))

Bibliography

Ackermann, Rudolph. The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions, and Politics . Vol. 9 (1813). Internet Archive, from a copy in the library of the Piladelphia Museum of Art. Web. 5 October 2020.

Assael, Brenda. The Circus and Victorian Society. Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2005.

Ayres, Brenda. Victorians and Their Animals: Beast on a Leash. London: Routledge, 2019.

Cornish, C. J. Life at the Zoo; Notes and Traditions of the Regent's Park Gardens. London: Seeley & Co., 1895. Internet Archive, from a copy in the Smithsonian. Web. 5 October 2020.

Cowie, Helen. Exhibiting Animals in Nineteenth-Century Britain: Empathy, Education, Entertainment. London: Pagrave Macmillan, 2014.

"Frightful Occurrence." The Times. 27 October 1857: 12. Times Digital Archive. Web. 5 October 2020.

"The Good Hippopotamus." The Times. 15 October 1850: 4. Times Digital Archive. Web. 5 October 2020.

Queen Victoria's Journals: Information site (with search facility).

Tait, Peta. Fighting Animals: Travelling Menageries, Animal Acts and War Shows. Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2016.

Ward, Steve. Sawdust Sisterhood: How Circus Empowered Women. Stroud, Glos.: Fonthill Media, 2016.

Created 5 October 2020