In 1867 at the annual Literary Fund dinner Philip Stanhope, the society's president praised Anthony Trollope for his recurring characters, “an invention” Stanhope attributed to Balzac. Trollope then counter-toasted Balzac's achievement using a different term, “[Balzac] was the man who invented that style of fiction in which I have attempted to work,” and Trollope went on to imply many readers do not follow a character's development sequentially over a cycle of novels: “the carrying on of a character from one book to another is very pleasant to the author; but I am not sure that all readers will participate in that pleasure” (Mullen, AT, Victorian 177; Hall, Trollope 302). By Balzac's “style of fiction” Trollope was (I suggest) calling attention to the whole mode Balzac has become famous for: the creation or, if you will, mapping of what seems to be a consistent & variously peopled world with a cast of psychologically complex recurring characters (Wall 123-24).1

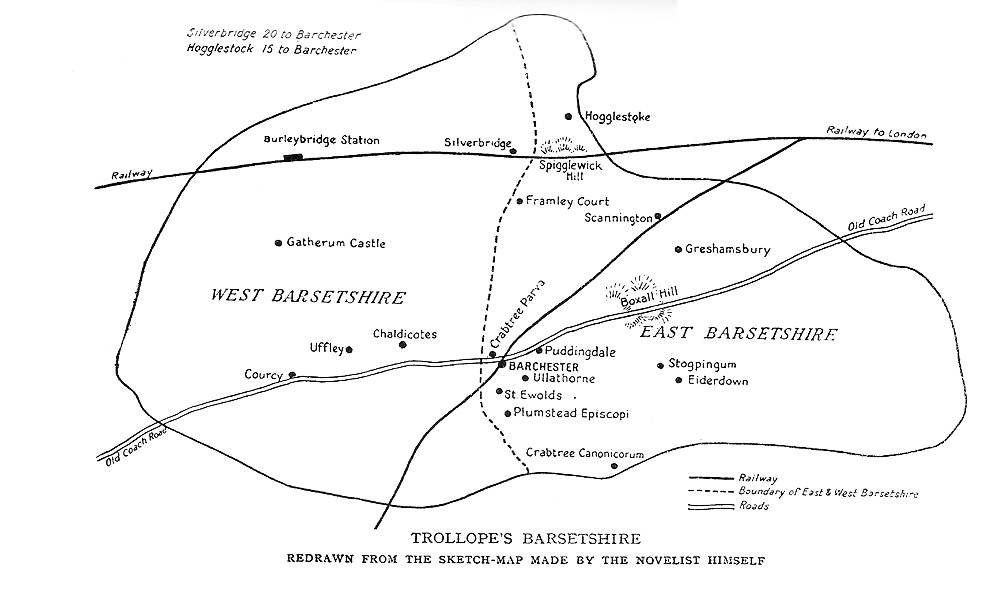

Like Balzac, Trollope created continuously sustained worlds for such characters to exist in, worlds which seem co-terminus with larger real terrains we experience, but are filled in with imagined places to the point that Trollope’s worlds require re-drawing of non-fictional maps (Hamer, CR introd, n.p.). Trollope's readers have assumed he worked out his maps carefully and he wrote twice of Framley Parsonage that since it was the fourth novel he had set in Barsetshire, he “found it necessary … to provide a map … for the due explanation of all these localities” (FP 14:184; A 154).1

This is Trollope's drawing of Barsetshire first printed in Sadleir's Trollope: A Commentary (1927)

Fervent fans have tried to prove the Barsetshire map is internally consistent while others have created walks in London from Trollope's novels (Sadleir 162-64; 397 see Tingay Bedside, Mapping). When in 1999 I attended a London Trollope Society annual general meeting, I experienced physically how Trollope is a selective and literal topographer of eighteenth-century London by walking with a group of Trollopians through one of six detailed London Walks which our guide, Bill Streeten, had drawn from the Pallisers, other Trollope novels and Trollope's life history. I have brought with me today, the map we followed:

2: This is the map drawn by Bill Streeten; it follows the course Mr. Bonteen and after him Mr Emilius took the night of the murder in Phineas Redux.

It's taken mostly from Phineas Redux: the bold lines include the route followed by a Mr Emilius, the character who murders Phineas Finn's rival and enemy, Mr Bonteen.3

My argument is that Trollope's visualized maps are a central means by which he organizes and expresses the social, political and psychological relationships of his characters and themes (Harvie 1-27), that they name places important to him personally; and that through his Irish maps he aimed to put Ireland into his English readers' imagined consciousness. In October 1859 he found himself pressured to put aside Castle Richmond, a tale set in Ireland in a famine year 1847, to write Framley Parsonage for the Cornhill, an imagined English county, Barsetshire book, as a successful career move. Trollope's Framley Parsonage has been looked at as the crucial novel which transformed his career; we will look at it as one of two novels4 that taken together reveal Trollope's evolution of a method for writing novels. I will show he visualized the intersection of hierarchy with social behavior and individual psychology in both Castle Richmond and Framley Parsonage by plotting their stories through movements of characters from site to site on a coherent map.

We will then turn to two mid-career to late novels, Phineas Redux, (written 1870-71), a dark “double” of the earlier Phineas Finn (Godfrey 94, Polhemus 178);5 and The American Senator (1875), set in Dillsborough county, a place that, together with its genealogies, is so minutely detailed, that readers regularly complain about what scholars defend as a novel to be “read for the sake of its opening chapters, which set before the reader in a few pages, the whole geographical and social pattern of an English county” (Sadleir, 397). Trollope's use of maps had changed; his later books set forth “geographies of power” which include new terrains and project a sceptical outlook.6 In Phineas Redux Trollope takes the reader into dangerous city streets to experience a Balzacian story where a change of site causes gains and losses of safety or respect (Moretti, Atlas, 108-14). In The American Senator the battle is to settle down at all. The struggle is aggravated because it must be hidden and yet all respond to one another by where and how much you are known to have settled down with; yet money helps only in certain places to ignore not to supersede rank or customs, all three of which (money, rank, custom) are rejected as a measure of someone's worth by the American Senator Gotobed (Tracy 210).7

Mapping Ireland

Until very recently Trollope's Anglo-Irish novels were ignored by the published apparatuses of literary criticism,8 and his two Phineas novels whose hero is a young man from western Ireland whose votes on Irish political issues are crucial turning points in the novels not even admitted to be Anglo-Irish.9 Yet during the first thirteen years of his published writing life (1847-60), in the face of mockery, near silence and total financial failure as a writer, Trollope mapped Ireland thoroughly, and later returned to Ireland to deal with class, ethnic, religious and political conflicts between the Irish and English.10

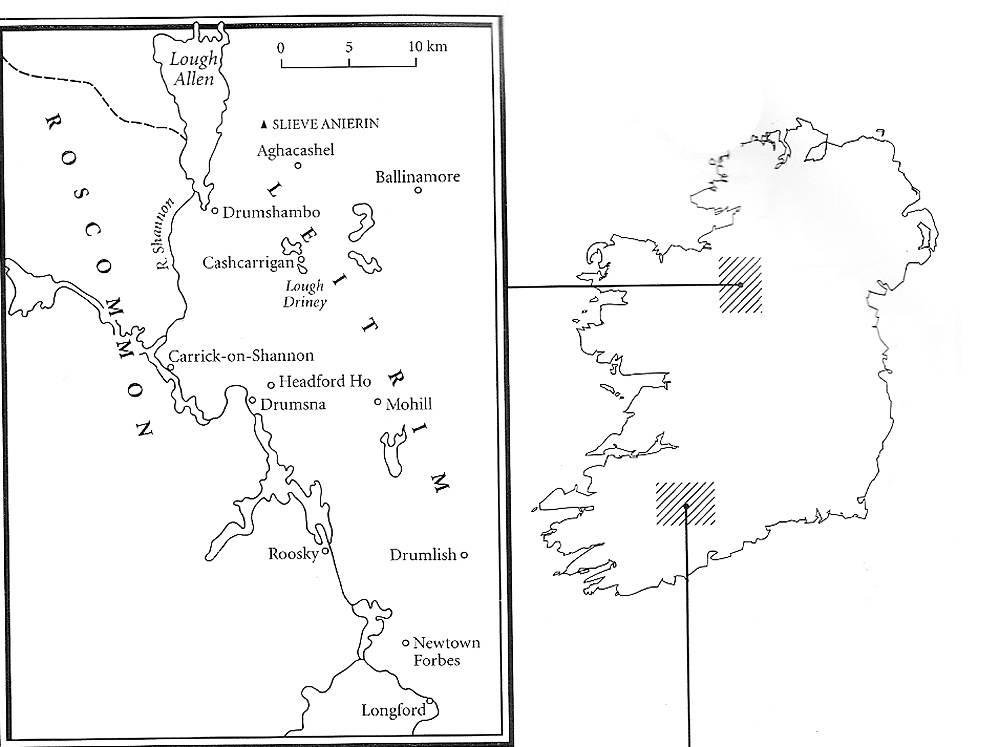

Trollope's mapping of Ireland follows his own movements as he lived in different residences to oversee and map postal routes. In 1841 he first came to live in Banagher, a south mid-lands town “permeated by a sense of history” from nearby ruins and ring-forts, and traveled across the province of Connacht, east of Leitrim; the immediate prompting for his first published novel, Macdermots of Ballycloran (written 1843-45) was a mansion in an “unnaturally ruined state” that Trollope came upon while walking in Drumsna, a Leitrim village alongside the river Carrick-on-Shannon (Macdermots 1-3)..

3: This map encompasses the main action of The Macdermots of Ballycloran and indicates one of the central areas in which The Land-leaguers takes place.

By 1844 he had moved to lodgings in the borough market town, Clonmel and its nearby mountainous landscape is central to the novel's denouement, which exposes the colonialist paranoia of the Anglo-Irish establishment (Moody, Trollope on the 'Net 6-29). His second novel, The Kellys and Okellys encompasses imagined and real places in counties Galway, Mayo, Kildare, and Dublin, where the action begins with a mass meeting and includes accurate observations on Daniel O'Connell's state trial. Illegal bars and hunting tracks, assizes, and fairs, shops and courthouses, are described with a seeming actuality by use of contemporary events and are precisely enough located so we can know where we are using non-fictional contemporary maps and thus judge the status of the place and characters' activities in the novels' scheme of things. He then labored for months on something like a third of a large travel book on Ireland where he “did the city of Dublin, and the county of Kerry, in which lies the lake scenery of Killarney; and ... the route from Dublin to Killarney” (A 87).

He then had to put aside his pen. Even he could not write much from 1851 for about two years, when he moved to the southwest corner of Ireland, Mallow (county Cork), where, with nearby Kerry, he set Castle Richmond, and with Mallow as his base, literally rode and drew what he thought were doable mail routes for postmen to traverse across south, west and mid-Ireland, so successfully and efficiently that he was sent to do the same over a wide swath of southwestern England and Wales (A 88).a href="#11">11 In 1853, he returned to Ireland to live first in Belfast, then Donbrook, a Dublin suburb (A 88), and surveyed the Irish northern counties (A 95-96).a href="#12">12 The sites for his last novel, The Land-leaguers include Ulster, Dublin, and Galway, where political murders had just occurred, and he describes houses near and like recognizable ones described in the press at the time (Tracy “Instant Replay” 35-39).13 It was around the time of Trollope's return to Ireland that he conceived Barsetshire while walking near Salisbury Cathedral – I suggest out of thwarted longing for the English countryside. Three years later Trollope visited the cliffs of Mohair, at the extreme western edge of county Clare; when first married he and his wife had visited the cliffs; he made the romantic isolated place central to An Eye for an Eye, the novel of a young English officer's betrayal of a Catholic Irish girl (Sutherland Introd., Eye x).14 Phineas Finn, hails from Killaloe, county Clare, and first stands for Loughshane, imaginary but placed on the confines of Clare, Limerick, Tipperary and Galway (McCourt).

Here I can only suggest how just one patch of Cork and Kerry in Castle Richmond works analogously to what we find in Framley Parsonage:

4: Sadleir regularized Trollope's Barsetshire map so as to make it more consistent with what's found in the Barsetshire books (Commentary)

In Framley Parsonage we literally move from one group of characters and their place to another as we read each chapter. Bill Overton easily sums up the novel's action and themes by describing its map:

Six forces are active in the county. The Proudies live in Barchester itself, the Grantleys to the south, Sowerby and the Duke of Omnium to the west, the Luftons to the north [and further north yet the Crawleys at Hogglestock], with the Greshams to the east [as well as the Ullathornes]. When the novel opens, the balance of power is precarious. There is an alliance between the Grantlys and Luftons, countered by another between the Duke of Omnium and Sowerby. But the latter's estate is heavily mortgaged to the Duke, and if (as seems likely) it is absorbed by him, the Duke who is already by far the richest landowner in the county, will become dangerously powerful ... [Overton 61-64; see also Polhemus 65-76]

Mark Robarts, Trollope's hero, makes the mistake of thinking he can rise by allying himself to Mrs Proudie and the Duke in the west (respectively shown to be power-hungry or a liar). Trollope's older heroine, Lady Lufton in the east fails to understand the inner nature of someone must be taken into account: she rejects Trollope's heroine, Lucy Robarts because Lucy lacks presence as the unmarried sister of Lady Lufton's vicar living in a parsonage. Miss Martha Dunstable, a single woman of no rank or estate, but with large sums of money from sales of a quack remedy, outbids the ever-encroaching Duke for Sowerby's Chaldicotes in the west and thus “restores” a balance of power while Lucy saves the Crawleys in northeast Hogglestock by going there unostentatiously and without regard to what this does to her status to nurse the wife of the impoverished curate, Josiah Crawley. These acts contrast to Mrs Proudie's pretenses she is helping Papua, the Philippines, Borneo, the Moluccas which places in the “Southern Ocean,” Sowerby, the novel's corrupt politician maps in a political speech as part of England's active concern (FP 95-96; Overton 62-63).

Castle Richmond relies similarly on a chapter by chapter emerging topographical allegorical description. As the book begins three houses are contrasted symbolically: Desmond Park is ancient Ireland with wooded meadows, but now without funds; its proud Countess of Desmond must marry her daughter, Clara, to a wealthy heir. The solvent Castle Richmond has such an heir, the upright Herbert Fitzgerald, who may however be illegitimate. While the barony of Desmond is “a figment of Trollope's imagination,” the name Desmond is “well-grounded in history” (Godfrey, “Castle Richmond”). Desmond Court is north of Ballvourney and Macroom "in a bleak unadorned region, almost at the foothills of the Boggergah Mountain, and south of Kanturk.

5: This is south-west Ireland where Castle Richmond is set and includes the actual place-names in Ireland in the 1840s, to which Trollope's text calls attention.

This is a fully-described real town fallen into desuetude where we meet the corrupt men blackmailing Castle Richmond from Kanturk's less then reputable chief hotel. To the north is Hap House where Owen Fitzgerald, the romantic hero lives on the banks of Blackwater. Castle Richmond and Hap House are both half-way between Kanturk and Mallow where Trollope lived.15 Trollope's political purpose was to demonstrate the descriptions of devastation in Ireland were exaggerated (Examiner 3rd Letter, 6 April 1850:14), as we can see from one of his smaller topographies, the Kantuck hotel itself, on an unfashionable street, poor and derelict but far from crazed with starvation:

There was but one window to the ['sitting, or coffee'] room, which looked into the street and was always clouded by a dingy-red curtain … A strong smell of hot whisky and water always prevailed, and the straggling mahogany table in the centre of the room, whose rickety legs gave way and came off whenever the attempt was made to move it, was covered by small greasy circles … [in] the kitchen … lived a cook, who, together with Tom the waiter, did all that servants had to do … From this kitchen lumps of beef, mutton chops, and potatoes did occasionally emanate, all perfumed with plenteous onions; as also did fried eggs, with bacon an inch thick and other culinary messes too horrible to be thought of … [CR, Ch 6, 54-56].

Outside the Corridors of Power

Twelve years and eighteen novels later in Phineas Redux, Phineas's party's club located in central London on a street near where Bonteen's murder was perpetrated may seem worlds away from the Kantuck. For this novel Trollope appropriated a contemporary London street paranoia: his hero, Phineas, carries a deadly knobstick-cudgel (Godfrey 61-76, 101-7), which weapon Phineas brandishes to show how he would hit Bonteen if they should come to blows and is part of the evidence used to accuse Phineas of the murder.16 The configuration of these streets form a key bone of contention during Phineas' trial. But the methodology, atmosphere of the lodgings where Bonteen's murderer, Mr Emilius resides, and Macpherson's Hotel where Mr Kennedy, another man jealous of Phineas, stays when in London, are used as plot points and treated in an allegorical manner similar to Framley Parsonage and Castle Richmond. What's new and different is the movement out into the streets, the novel's insistence that low status milieus where life is desperate shape its hero's destiny.17

In the novel the defense, prosecuting attorney and witnesses suggest what did or did not happen in these streets, and what the one witness on the dark night, Lord Fawn, saw or thought he saw (e.g., PR 49:79-84; 50:94; 62:197-201; 63:208-9). In the manner of crime stories, to exonerate Phineas someone has to challenge the assertion that a gray overcoat seen on the presumed murderer from afar by Fawn is the one Phineas was wearing that night, and the deduction that therefore the murderer is Phineas. Mr Emilius's alibi depends upon his assertion that he was inside his room inside a boarding house all night because in the general way of such places, the doors were all locked and he lacked a key. One of Trollope's heroines, Madame Max, in love with Phineas, goes on a quest to find a second key. A comparison of her visit to Mr Emilius's landlady, Mrs Meager, and Phineas's obsessive return to the streets in the dawn hours of the night he was declared not guilty as presented in Trollope's novel and the 1974-75 BBC Pallisers mini-series, scripted by Simon Raven,< a href="#18">18 will bring out clearly how status-inflected geography, gender, and streets well outside the corridors of power and upper middle class lives influence the outcome of the trial for the novel's hero and make visible a painful truth he realizes as a result of his ordeal.

In the novel Madame Max hires a cab to drive her well out of her usual Park Lane area to visit Mrs Meager, in her “uninviting” lodgings on Northumberland Street, “just opposite to the deadest part of the dead wall of Marylebone Workhouse,” which Trollope as a young man saw from his window in London in the first years of his employment in the London post-office (PR 66:141-47 and Pallisers 9:18, Episode 3, scene 12). The min-series, true to costume drama's aesthetic preferences seats them in Madame Max's luxurious be-flowered apartment, but the visibilia of filmed scene includes a piling up of clinking gold coins19 as the desperate Mrs Meager tells yet another memory from that night in the lodgings

6: Madame Max (Barbara Murray) and Mrs Meager (Sheila Fay), Part 9, Episode 18. from the 1974-75 BBC Pallisers, for which Simon Raven wrote the script.

Trollope shows us women with no recognized offices reach needed truths that powerful men could not find because the men ([as Phineas's mentor Monk's (Brian Pringle) dismissive words suggest]) could not be bothered to come to such a low place to look for information nor would Mrs Meager have spoken to such men frankly had they come.20 Raven's dialogue makes explicit Trollope's text's inferences: Madame Max (Barbara Murray) projects real sympathy for the wary-eyed tense landlady (Sheila Fay): “Poor Mrs Meager what a very difficult life you must have.” And thus the existence of an extra key and, unexpectedly, a second gray coat now in the pawnshop, is told of.

In the book and mini-series Phineas in a sort of trance obsessively walks the walk Mr Bonteen, after him Mr Emilius and then our Trollopian group in 1999 followed.

7: What Lord Fawn (Derek Jacobi) Saw, Part 8, Episode 17 from Pallisers, for which Simon Raven wrote the script.

In book and mini-series Phineas was shocked and made desolate when he realized just about all his friends were prepared to believe he could murder a man treacherously, in such cowardly manner “to obtain advancement.” Mr Bonteen was murdered by a blow from the back, an ambush in which someone crushed Mr Bonteen's scull (Pallisers 9:18 and 9:19). Unlike Trollope's text, Raven's script calls for Bonteen's ghost (Peter Sallis) to appear, producing a televisual psychodrama of Phineas (Donal McCann) looking at these strange streets and then admitting aloud he does not regret Bonteen's murder and the suspicion was understandable. Trollope's narrator suggests this by yet another site topography:

. . . he went on till he came to the end of Clarges Street, and looked to the mews opposite to it, – the mews from which the man had been seen to hurry. The place was altogether unknown to him. He had never thought whither it had led when passing it on his way up from Piccadilly to the club. But now he entered the mews so as to test the evidence that had been given, and found that it brought him by a close turn close up to the spot at which he had been described as having been last seen by Erle and Fitzgibbon.

Phineas breaks out into verses from a poem by Barrett Browning where the speaker looks at the social world from a permanently estranged perspective (PR 67:245-56; Pallisers 9:19, Episode 7, scene 6).21

In The American Senator Trollope dramatizes repeated estrangements, within families as well as from communities; emigration of sons, threatened homelessness for daughters, and business failures of males responsible for a family. Trollope's mapping is minute and continual: where you sit at a dinner table, where you stand in an estate tells how you are rated:

8: This is the map of Dillsborough, the central county of The American Senator (one of 9 maps published in Geroulds, drawings Florence Ewing, 1948)

His characters now self-consciously manipulate in accordance with where they literally are, and some – the American senator is not alone – see social life as basically ironically often dysfunctional except for the very powerful and careful.22

Trollope's double-edged defense of his memorable heroine, Arabella Trefoil has often been quoted:

“The critics will tell me that she is … the creation of a morbid imagination … I have known the woman … all the traits, all the cleverness, all the patience, all the courage, all the self- abnegation, – and all the failure … Think of her virtues; how she works, how true she is to her vocation [to acquire a rich and exciting titled husband], how little there is of self indulgence, or of idleness. I think that she will go to a kind of third-class heaven in which she will always be getting third-class husbands. [Hall, Letters, 2:710-11]

At the novel's close Arabella is relieved to emigrate to Patagonia (AS 76:530) with a husband who is an upper clerk in the foreign office whose name, Mounser Green, is a version of Trollope's own surrogate in some short stories. Amid the many stages of her trajectory, I single out a crucial one where Arabella unflinchingly breaks through all barriers surrounding and within the estate of Lord Rufford, a rich landowner and aristocrat whom she insists has asked her to marry him. She accosts Rufford in his park (AS 66-67:457-68), accuses him of treating her cruelly and challenges him to deny he asked her to marry him. In fact, he had only kissed her and allowed her to imply that he loved her (cf AS 39:266-68 and 67:464-67). The narrator dubs her “a kind of Medea” to Rufford's “Jason” (AS 66:457). She wins Rufford's admiration, but Lady Penwether, Lord Rufford's sister, standing just inside the house by the door Arabella went through, interferes by sending Lord Penwether whose presence stops Rufford and Arabella's debate with an invitation to a dinner Arabella rightly refuses to be tempted by. Arabella's final ejection is expressed as a site: “It seemed to her as she stood by the lodge gate, having obstinately refused to enter the house, to be an eternity before the fly came to her” (67:467).

I have written elsewhere about the brilliance of the individual interwoven correspondences placed throughout this novel: these expose the economic and social antagonisms of the human communities from which each is sent.23 Characters' natures as seen by others change as these games of ambition work out. Once one of the novel's heroes, Reginald Morton, hitherto apparently solitary, even bookish (AS 27:181), inherits the beautiful Bragdon Estate.

9: The Bragton Estate, fought over by the Morton family, where Mary Masters grew up, and at the end of The American Senator inherited by Reginald Morton (another of the 9 maps).

Reginald takes up hunting and participates in the community life as is required of a squire (AS 79:546). The novel's exemplary heroine, Mary Masters, has grown up to be lady-like since she was brought up at Bragton by Reginald's aunt; all novel long Mary's jealous stepmother will not allow her a private space in her father's house secure from harassment because the stepmother wants Mary to marry a farmer and tries to prevent her from visiting Cheltenham where Reginald's aunt lives genteely. The theme is given good-natured comic rendition in a chapter about a parrot on a train who echoes the characters in his carriage area pointedly and has to be silenced by a cage cover (AS 27:180-87).

Geographies of Places into Novels

Places, their visibilia, and spatial arrangements provide Trollope's novels with their structure (Thrale, Cadbury). Arguably as Balzac is said by some to have “turned a city [Paris] into a novel” (Calvino 141) so Trollope turned Barsetshire and attempted to turn all Ireland into novels.24 His map of London is selective:

10: A diagrammatic outline of the places in London Trollope's novels encompass (probably by Bill Streeten); comparable to the outlines Moretti draws of Balzac's Paris and Dickens's London (Atlas).

Here he branches out to include places where the privileged find they must cope with the people they find there. In his last books habitual social arrangements and status protections attached to places are shown to be fragile but all the more clung to by the characters who can manage it. And he never forgets his own involvement. Trollope's maps reveal a powerful political, psychological and autobiographical imagination at work making the Trollopian imagined worlds his readers react to as true and which some scholars have argued accurately represent his 19th century worlds.

Last modified 30 July 2013.