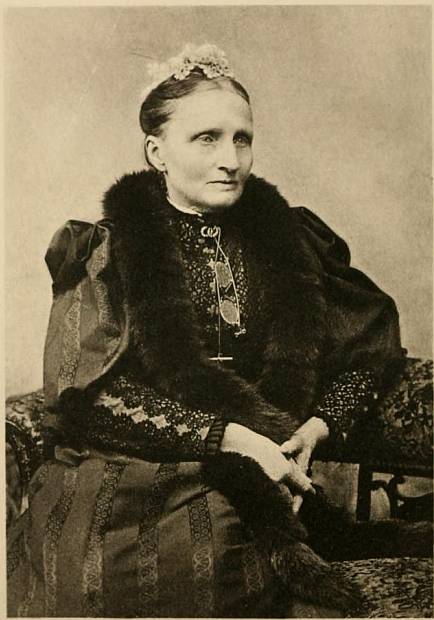

Emma Marshall, from the frontispiece of Beatrice Marshall's biography of her mother. [Click on the thumbnail for a larger image.]

Emma Marshall (1830-1899) was immensely prolific and popular in her own times, especially as a children's author; Sidney Gottlieb's essay on her appears in a collection of essays on George Herbert because the metaphysical poet/priest features prominently in two of her historical novels: Under Salisbury Spire in the Days of George Herbert: The Recollections of Magdalene Wydville (1889), and A Haunt of Ancient Peace: A Story of Nicholas Ferrar's House (1896). Gottlieb focuses on the former, in which Herbert plays the more central part. His essay raises some interesting questions both about minor authors of the Victorian period, and about Victorian historical fiction in general.

Since Marshall is so little remembered now, Gottlieb has to introduce her in some detail. Born Emma Martin, near Cromer in Norfolk, the future writer had a Quaker background, something, Gottlieb feels, that helps to account for

her sense of individuality and independence; her calm but determined outspokenness on a variety of controversial topics; her model of spirituality as personal, not highly formalized or institutionalized; her commitment to communal living, beginning with the extended family; and her dedication to a life of energetic activity, public service and charity, personal responsibility and morality, education, and peace.

This certainly rings true, reminding us of an earlier Quaker woman with such qualities, the strong-minded reformist and philanthropist Elizabeth Fry (1780-1845), who was also from Norfolk. More questionable perhaps is Gottlieb's suggestion that Marshall's love of nature and the arts was rather less "Quaker-like" (256). As far as nature is concerned, at least, Mary Howitt (1799-1880), a similarly unflagging author with a Quaker upbringing, loved to pass on her intimate knowledge of nature in her children's books.

Marriage to a banker in 1854, after a move to Clifton, near Bristol, brought Marshall one of her most important roles in life, as the mother of nine children; she also took in schoolchildren as boarders. Her other important task was writing. From 1861 onwards until close to her death in 1899, she wrote around 200 novels and tales, mostly for children and young women but including many painstakingly researched historical novels. One spur to all this activity was the collapse of her husband's bank in 1879, which saddled him with enormous debts. Her efforts must have helped: Gottlieb quotes one recent source as saying that "during her lifetime she had more fiction titles on the shelves of Mudie's subscription library than any of her contemporaries, including popular writers for boys and Charlotte Yonge herself" (257).

By the time Marshall came to write about George Herbert she had for many years (since 1852) been a member of the Anglican church, and clearly felt a deep affinity to her subject. Examining Under Salisbury Spire in detail, Gottlieb admires her for "mixing outright fiction and reported history, and making George Herbert a complex and dynamic figure rather than an unimaginative embodiment of a via media and a vehicle of knee-jerk nostalgia and dull hagiography" (270). What is most surprising about Marshall's version of him is the incorporation of a romantic courtship and marriage into his last years. Following Izaak Walton's Life of 1675, the poet is generally thought to have made a match largely for practical reasons. But happy domesticity was part of Emma Marshall's and the age's credo.

The important point for Gottlieb, as a Herbert scholar, is Marshall's "role in the late nineteenth-century reevaluation of Herbert" (270). But his essay is also valuable for bringing to our attention not only Marshall herself but the whole sweep of historical fiction that was so successful at that time, whether primarily for children or, like this one, for adults. It also raises questions for students of the Victorian period. Historical fiction might be expected to date well, and the genre itself continues to thrive: the Man Booker Prize of 2009 was won by Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall, about Thomas Cromwell. Note also our current rewriting of the Victorian period. But most Victorian historical fiction has faded from the literary landscape, along with the work of Sir Walter Scott himself, who did so much to popularise it for the Victorians. Of course, each age brings its own preoccupations and style to the rewriting of history. What other reasons could there be for the precipitous decline in popularity of works like Marshall's? Which historical novels of this period have survived, and why?

Sources

Gottlieb, Sidney. “Under Salisbury Spire with the Fictional George Herbert.” George Herbert’s Pastoral: New Essays on the Poet and Priest of Bemerton. Ed. Christopher Hodgkins. Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 2010. 255-272.

Marshall, Beatrice. Emma Marshall: A Biographical Sketch. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1901. Web. 6 May 2010

Sutherland, John. The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction. London: Longman, 1988.

Last modified 6 May 2010