The third and fourth parts of Hogarth's The Humours of an Election (1755). Click on the images to enlarge them and obtain more information.

The young radical Charles Dickens sums up his derisive attitude towards electioneering even in the name of the fictitious East Anglian borough holding the bye-election: Eatanswill (eat-and-swill). The twenty-year-old former parliamentary reporter's take on the nation's much trumped up representative democracy involves underscoring its follies, rather than, like Hogarth's scathingly satirical scenes in The Humours of an Election (1754-55), exposing its hypocrisy and immorality. As Bruce Kinzer states regarding the continuity of dubious election practices after the passage of the Great Reform Bill in 1832, "Heightened party conflict and the persistence of bribery and treating (plying electors with food and drink) meant that the cost of contesting elections remained high" (254), ensuring that the wealthy (the traditional aristocracy and the newly rich industrial capitalists) would continue to control election outcomes.

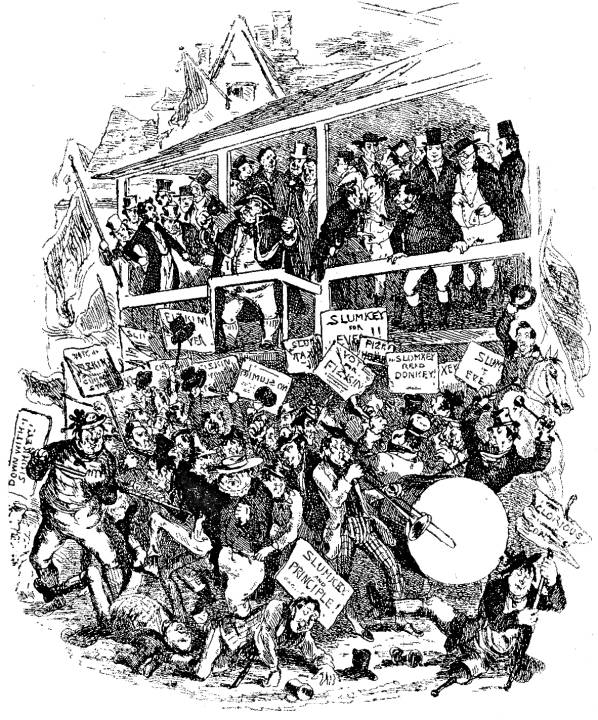

Left: Phiz's August 1836 Pickwick illustration, The Election at Eatanswill. Click on the image to enlarge it and obtain more information.

When Dickens wrote the thirteenth chapter of The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club in mid-1836, the Great Reform Bill of 1832 was still recent history, and the extended franchise undoubtedly impacted the subsequent bye-elections that the young shorthand reporter had covered, including the local election at Bury St. Edmunds, which seems to have inspired Dickens to create Eatanswill, Essex, with its twin campaign headquarters, The Town Arms for the Blues (the Tories or Conservatives) and The White Hart for the Buffs (Whigs or Liberals). In all likelihood, Dickens's collaborator on most of the project, Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'), developed the anarchic election scene by incorporating Dickens's suggestions and the text of "Some account of Eatanswill; of the state of the parties therein; and of the election of a Member to serve in Parliament for that ancient, loyal, and patriotic borough" in the Hogarthian engraving The Election at Eatanswill. The subject of Thomas Nast in the American Household Edition (1873) and Phiz (1836, 1874) is not old "Blue" (Tory or Conservative) Samuel Pickwick, retired capitalist and opponent of wide-scale social change; rather, the illustrators focus on the candidate whom Pickwick supports, "the Honourable Samuel Slumkey himself, in top-boots, and a blue neckerchief," who is playing to the multitude assembled in front of The Town Arms Inn. The competing bands and banners appear in the original Phiz illustration, but in neither Household Edition volume:

Left: Phiz's 1873 plate: He has come put . . . . Right: Thomas Nast's He's kissing 'em all!. Click on the images to enlarge them.

There were bodies of constables with blue staves, twenty committee-men with blue scarfs, and a mob of voters with blue cockades. There were electors on horseback and electors afoot. There was an open carriage-and-four, for the Honourable Samuel Slumkey; and there were four carriage-and-pair, for his friends and supporters; and the flags were rustling, and the band was playing, and the constables were swearing, and the twenty committee-men were squabbling, and the mob were shouting, and the horses were backing, and the post-boys perspiring; and everybody, and everything, then and there assembled, was for the special use, behoof, honour, and renown, of the Honourable Samuel Slumkey, of Slumkey Hall, one of the candidates for the representation of the borough of Eatanswill, in the Commons House of Parliament of the United Kingdom. [Chapter XIII]

Although the nature of elections in support of British parliamentary democracy must have become somewhat less adversarial, corrupt, and raucous between 1834 (the date of the Sudbury bye-election covered by young reporter Charles Dickens) and the 1870s, Phiz merely reprised his 1836 engraving The Election at Eatanswill (Part 5: August 1836) for his 1874 woodcut for the British Household Edition. Whereas Phiz's baby-kissing Tory candidate seems to have some tender regard for the infant he is about to kiss (centre), Nast's great-coated politician holds aloft a seemingly paralyzed toddler. The comparable juxtaposition of the candidates, the crowd — more raucous in the American version, more benign in the British — as a backdrop, and in particular an almost identical positioning of the sign "Slumkey for ever" (left rear) suggests that the later artist was responding to the earlier's work. In the crowd in the British illustration, the young mothers and their infants predominate — Phiz includes eleven young women and nine children, six of them babes in arms. In contrast, Nast has included only three children and one baby; and his Slumkey supporters are largely male, underscoring the fact that, even in the 1870-s, adult females were still disenfranchised, and would remain so until universal female suffrage was legislated in two separate twentieth-century bills (1918 and 1928) and in the United States nationally in that same decade.

The instigator of this electoral strategy for Samuel Slumkey in Chapter XXIII of Pickwick is none other than Mr. Pickwick's and Mr. Wardle's solicitor, Mr. Perker, who had earlier negotiated with the rapscallion Alfred Jingle at The White Hart in the Borough (Southwark) on behalf of Wardle and his sister. We may assume that, since neither Pickwick nor his comrades appear in either Phiz's or Nast's illustrations, the perspective from which we regard each scene is theirs. Significantly, Dickens arranges for Mr. Tupman and Mr. Snodgrass, his disciples, to stay at a third inn, The Peacock, suggesting that they are relatively non-aligned observers of the election fray. To underscore Pickwick's Tory affiliations, Dickens makes him the house guest of Mr. Pott, editor of the local Conservation organ, The Gazette. The vociferous supporters whom both Phiz and Nast describe, a labourer in linen smock-frock and a butcher in a cotton bib, would not seem to be traditional Tory enthusiasts; in fact, these are the very proletarians whom Conservatives in 1832 sought to exclude from the electorate. Consequently, Nast seems to be implying that they have been suborned or bribed into rallying enthusiastically for the establishmentarian candidate. Thus, both Dickens and his illustrators seem to be implying that the goals of electoral reform enshrined in the Reform Act of 1832 are yet to be achieved, despite the modest extension of male suffrage to include adults who owned or occupied property worth a minimum of ten pounds per year. The size of the electorate might have shifted from 11 per cent of the overall adult male population in 1831 to 18 per cent in 1833, and even extinguished a number of rotten and pocket boroughs, rendering the Commons more representative, but old political usages, implies Dickens, die hard.

Related Material

- An introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

- Illustrators of Dickens's Pickwick Papers in the 1873 Household Edition

References

Dickens, Charles. The Pickwick Papers. Illustrated by Robert Seymour and Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman & Hall, 1836-37; rpt., 1896.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. The Household Edition. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. New York: Harper and Brothers 1873.

Dickens, Charles. Pickwick Papers. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

Kinzer, Bruce L. "Elections and the Franchise." Victoria Britain: An Encyclopedia. Edited by Sally Mitchell. Garland Reference Library of Social Science (Vol. 438). New York and London: Garland, 1988. Pp. 253-54.

Last modified 15 November 2019