In June 1851, the year of the Great Exhibition, Dickens's Household Words discussed another aspect of international commercial activity not included in this first great international fair — the opium trade. Henry Morley, the writer on staff who covered foreign affairs, takes a disturbingly exhuberant approach to what today we see as drug addiction:

Opium pipes, bring us! Ha! a hollow cane, closed at one end, with a mouthpiece at the other; near the centre is the bowl, of ample size, but with an outward opening no bigger than a pin's head. We recline luxuriously — looking down on the gay colours of the Chinese crowd, we take our long stilettos, prick off a little pill of opium from its ivory reservoir, and burn it, dexterously, in the spirit lamp; then twist it, judiciously, about the pin's head orifice. Three whiffs and it is out, and we are more than half deprived of active consciousness. Let us repeat the operation. Practised smokers will go on for hours; a few whiffs are enough for us. Another languid gaze at the pagodas, and the flowers, and the water, and the Chinamen; now some more opium to smoke! [Morley, p. 331]

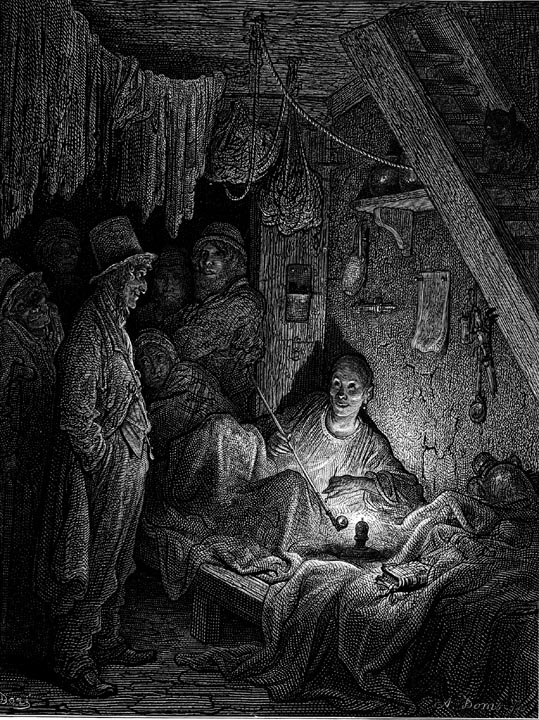

Opium Smoking — The Lascar's Room in "Edwin Drood" by Gustave Doré (1872).

Morley's exuberant style belies the social and medical evils of opium-smoking experienced by China and other nations during the nineteenth century, to say nothing of the disastrous economic, political, and military impacts. To locate the issues behind the First and Second Opium Wars as these are reflected in the narrative of Dickens's 1870 novel is complicated by the fact that The Mystery of Edwin Drood encompasses not merely two different scenes of action — London, especially disreputable Shadwell in the East End, where the story opens, and clerical, traditional Cloisterham — but also two different times. The time of writing is reflected in the opium den setting and references to engineering projects in Egypt (The Suez Canal having just opened), but the time of the action (probably the mid-1840s) is evident in the lack of direct rail service between London and Rochester. The time of writing is closer to the Second Opium War (1856-1860), while the time of the action is closer to the First Opium War (1839-1842).

As early as the seventh century A. D. Arab traders had introduced opium to China as an anodyne and palliative, and indeed for these purposes it remained perfectly legal even in Great Britain until the Pharmacy Act of 1868 restricted its use as "laudanum," the narcotic suspended in an alcohol solution used in a wide variety of patent medicines. As Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "Kubla Khan" (1797), Thomas De Quincey's Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821; text) and Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone (serially published in 1868 in Dickens's All the Year Round) make clear, however, the English like their Chinese contemporaries began to take note of the drug's less benign effects, especially when pleasure-seekers deliberately abused the drug to seek the delightful oblivion that Henry Morley describes above. When Dickens began writing Drood, opium dens were not merely limited to the Treaty Ports of contemporary China, for two entrepreneurs were driving a thriving trade in both Whitechapel and Shadwell Basin. One of these Charles Dickens almost certainly visited in writing the novel, and he probably had read about opium-smoking in an article in London Society in 1868 and "In An Opium-Den" in The Ragged School Union Magazine that same year. Moreover, Dickens was probably familiar about the social consequences for China of opium importation as a result of Henry Morley's Household Words review of John F. Davis's China, During the War and Since the Peace, a piece that Morley wittily entitled "China with a Flaw in It" (HW 5, 3 July 1852). Dickens as the "Conductor" of Household Words undoubtedly read with editorial care George Dodd's "Opium: Chapter the First. India" and "Opium: Chapter the Second. China" in August, 1857. All of this readily available material would have given Dickens reliable information about Anglo-Chinese Opium Wars.

References

Morley, Henry. "Our Phantom Ship: China." Household Words 66 (Saturday, 28 June 1851): 331.

Last modified 25 June 2005