eir’s work for adults took the form of closely observed representations of an extraordinary menagerie. He excelled at drawing dogs and poultry, but his range extended across all species; his images record appearances while also capturing the subject’s vitality, and contemporaries noted his capacity to register ‘life’. Though journalistic in approach he has an innate, naturalist’s sensitivity that goes beyond verisimilitude.

This approach closely reflects the complex dynamics of Pre-Raphaelitism, ‘copying from nature’ while embodying an interpretation or poetic perception of his subjects’ inner character. It also reflects the artist’s status as an autodidact, allowing him to work within his chosen genre while never adopting the conventionalities of Landseer and others such as John Frederick Herring (who was briefly Weir’s father in law). In Weir’s observational art there is always a sense of the subject being re-discovered each time; his illustrations rarely degenerate into formula or conventionality, and always preserve the aesthetic balance between realism and expression.

Some of the best of his observations appear in The Illustrated London News; the first appeared in 1847, and the final ones, almost sixty years later, in the period after 1900. A newspaper might not seem an obvious venue for animal pictures, but Weir was given opportunities in the form of illustrations for articles on new breeds – notably livestock and poultry – and in images representing the exhibits at country shows, amateur breeders’ clubs, and new acquisitions for London Zoo. Everything from bulls to cats, from dogs to parrots, appear in these pages. Usually in the form of broadsheet engravings, Weir’s images are models of versimilitude while achieving an intense, dream-like beauty; finely cut, sometimes by the artist himself, they are poetic versions of the Darwinian catalogue in which scientific exactitude is half-eclipsed by the artist’s playful inventiveness, fusing ‘fact’ and visual pleasure.

Two illustrations by Harrison Weir: Left: Praise of Country Life. Right: The Only One — The Earth. [Click on these images to enlarge them.]

Weir intensifies his effects by combining several species within one frame. In his designs for The Illustrated London News he typically arranges his subjects into a hierarchical series of tableaux, essentially a column with a frieze placed at the top of the page and the others below it. This procedure is exemplified by his reportage of ‘Birds from the Crystal Palace’ (December 4, 1858, p.522), and in an image (somewhat bizarrely) combining dogs and poultry from ‘The Prize Poultry, Pigeons, and Dogs at the Birmingham Show’ (Supplement, December 8, 1866, p.557). The second of these typifies Weir’s versatility – but its emphasis on the swelling plumpness of both species makes a half-joking, half-poetic connection between them. George Levine has noted how Darwin’s ‘project’ was not only a matter of stressing variety; it also posited the idea that ‘all living things constituted a commonality’ (p.170), and there are numerous occasions where the artist makes visual and structural connections between the apparently dissimilar.

Left: Birds from the Crystal Palace Show. Right: Prize Poultry, Pigeons, and Dogs at the Birmingham Show. [Click on these images to enlarge them.]

His anatomical and behavioural observations of animals is continued in many other publications for adult consumption. Some of these are textbooks with a practical application, notably Our Cats and All About Them (1889), which models the ‘standard of excellence and beauty’ required for showing prize felines, and The Sheep and Pigs of Great Britain, a picture book offering information and hints on the beasts’ ‘history and management’ (1877).

Some of these practical studies contain chromolithographic designs in imitation of early work for Baxter, and Weir maintained an interest in colour throughout his career. Many of his books appeared in black and white and in colour; sometimes chromolithography is used, but his work more often took the form of wood-engravings ‘plain’, or coloured in, usually in lurid tones, and applied by hand. Others, engraved by Edmund Evans, were coloured wood-blocks in which the tints were applied using the relief process that was otherwise used in the production of Richard Doyle’s In Fairyland (1869–70) and Walter Crane’s ‘Toy books’ of the 1880s.

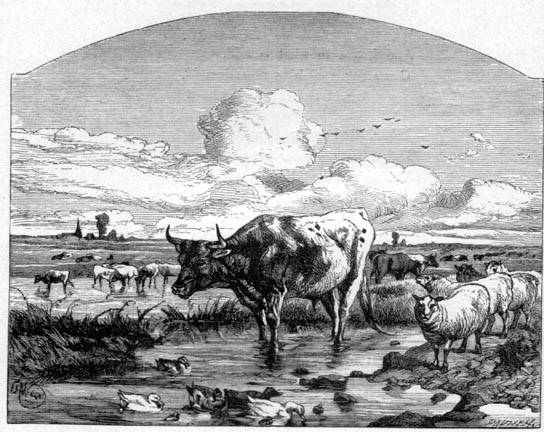

Weir also produced illustrations to accompany rustic literature, this time putting the emphasis on ‘poetic interpretation’. These images embellished several collections of poetry and prose, and provided a logical accompaniment to landscape designs by Myles Birket Foster. He drew serene illustrations for Robert Aris Willmot’s Summer Time in the Country (1858), in which the author presents rambling anecdotes from his diary of rural life. Sensitive to Wilmott’s interest in ‘naturalness’ (p.94), Weir’s ‘Cattle in shade’ (p.93) exemplifies his capacity to combine anatomical exactitude with an evocative representation of the animals’ element. Significantly, the cows wander randomly; the composition seems realistic, as if glimpsed in passing, and Weir avoids the conventional representations of cattle in the composed groups that are found, in imitation of Dutch models, throughout painting of rural life. He similarly provides an intensely atmospheric illustration of a swooping owl dropping out of the branches (p.18). This tellingly compares with an unknown contemporary’s version of the same event in the frontispiece to Stories about Birds (circa 1880). Weir’s is full of life; the other, while charming in the manner of folk-art, is a collection of observed details rather than a representation of the living creature.

However, his most accomplished designs for verse appear in The Poetry of Nature (1861). This book allowed him to play to his strengths: he contributed some lines of his own, edited and selected the verse, and was able to choose the poems that furnished him with the best subjects. The Poetry of Nature contains the usual blend of observation and feeling, but it also points to his interest in anthropomorphism. Some (though not all) of the poems accord with this purpose; he illustrates Wordsworth’s ‘Fidelity’ (pp. 36–9) in which the faithful dog stands guard over his fallen master, and he finds lessons in the eagle’s imperious cruelty, as it is described by Mrs. Barbauld (pp. 86–7). This focus is important, and is considered in detail in the next section.

Related Material

- Weir, anthropomorphism, and moralizing books for children and adults

- Animals and Victorian art

- Weir’s influence: Disney and American cartoons

Primary Works Cited and Sources of Information

Blatty, Joseph. Harrison Weir: Artist, Author and Poultryman. Beech Publishing House, 2003.

Brothers Dalziel, The. A Record of Work: 1840–1900. 1901; rpt. London: Batsford, 1978.

Elwes, Alfred. The Adventures of a Bear. London: Addey & Co., 1853.

Elwes, Alfred. The Adventures of a Dog. London: Addey & Co., 1857.

Funny Dogs with Funny Tales. London: Addey & Co., 1852.

George Cruikshank’s Table Book. London: Punch Office, 1845.

Grandville, J. J. Scenès de La Vie Privée et Publique des Animaux. Paris: Hetzel et Paulin, 1842.

Graves, Algernon. The Royal Academy of Arts: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors from its Foundation in 1769 to 1904. Vol. 3. London: Bell, 1905.

Hibberd, Shirley. Clever Dogs, Horses, etc. London: Partridge, n. d. [1867].

Houfe, Simon. The Dictionary of 19th Century Illustrators and Caricaturists. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Antique Collectors’ Club, 1978; revised ed., 1996.

Illustrated London News, The. 1843–66.

Ingpen, Roger. ‘Harrison Weir’. Oxford DNB. www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/36817, accessed 9 March 2013.

Kingston, W. H. G. Stories of the Sagacity of Animals. London: Nelson, 1892.

Levine, George. Darwin Loves You: Natural Selection and the the Re-Enchantment of the World. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006.

Maas, Jeremy. Victorian Painters. London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1978.

Pictorial Cabinet of Marvels, The. London: James Sangster, n.d. [1878].

Poetry of Nature, The.Selected & Illustrated by Harrison Weir. London: Sampson Low, 1861.

Redfield, James.Comparative Physiognomy; or Resemblances between Men and Animals. New York: for the author, 1852.

Stories about Birds. London: Cassell, Petter, & Galpin, n.d. [1880].

Summer Time in the Country. Ed. R. A. Willmott. London: Routledge, 1858.

Turner, Catherine Ann [Mrs Dorset].The Peacock at Home.London: Grant & Griffith, 1854.

Victorian Animal Dreams: Representations of Animals in Victorian Literature and Culture. Eds. Deborah Denenholz Morse and Martin A. Danahay. Burlington VT: Ashgate, 2007.

Weir, Harrison. Animal Stories Old and New. London: Sampson Low, n.d. [1885].

Last modified 1 April 2013