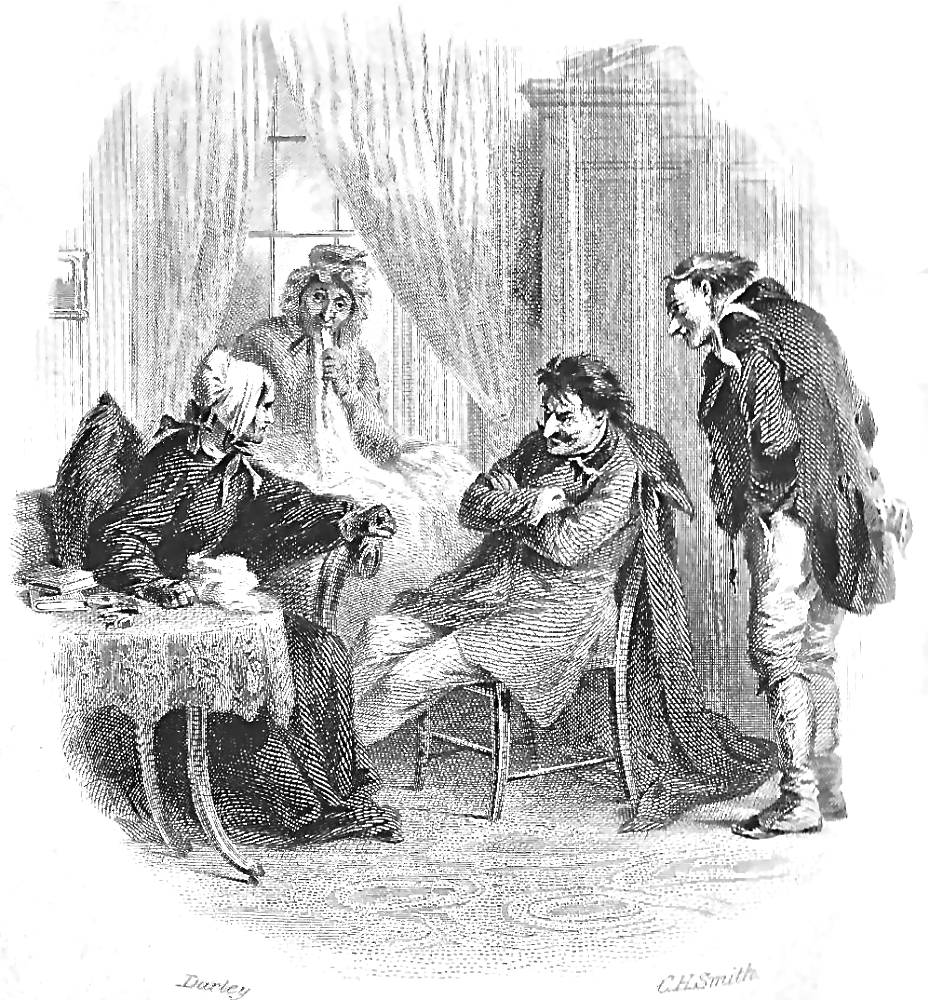

"But what — hey? — Lord forgive us!" — Mrs. Flintwinch muttered some ejaculation to this effect, and turned giddy — for Mr. Flintwinch awake, was watching Mr. Flintwinch asleep (See page 22), — Book I, chap. 4, in the Harper and Brothers Household Edition volume is the full title for Mrs. Flintwinch has a Dream, the short title as given in the Chapman and Hall printing. Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's fifth illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 10.6 cm high by 13.7 cm wide, framed. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

Mrs. Flintwinch crossed the hall, feeling its pavement cold to her stockingless feet, and peeped in between the rusty hinges on the door, which stood a little open. She expected to see Jeremiah fast asleep or in a fit, but he was calmly seated in a chair, awake, and in his usual health. But what — hey? — Lord forgive us! — Mrs. Flintwinch muttered some ejaculation to this effect, and turned giddy.

For, Mr. Flintwinch awake, was watching Mr. Flintwinch asleep. He sat on one side of the small table, looking keenly at himself on the other side with his chin sunk on his breast, snoring. The waking Flintwinch had his full front face presented to his wife; the sleeping Flintwinch was in profile. The waking Flintwinch was the old original; the sleeping Flintwinch was the double, just as she might have distinguished between a tangible object and its reflection in a glass, Affery made out this difference with her head going round and round. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 4, "Mrs. Flintwinch has a Dream," p. 22.

Commentary

The Clennam maid Affery, Flintwinch's wife, dreams (or apprehends while only half-awake) that she sees her husband with his double in the middle of the night. That Jeremiah Flintwinch has a double gives him the preternatural power of seeming to be in two places at once, and the double has the added advantage for Jeremiah of terrifying Affery and making her believe that she is delusional. Moreover, while Jeremiah can remain at his post in London, he can dispatch his twin brother, Ephraim to take papers concerning Little Dorrit's suppressed inheritance to the Continent for safe-keeping.

In this dark plate, reminiscent of the style of Phiz in Bleak House Mahoney captures Affery's fugue state, using chiaroscuro to suggest that the light from the room occupied by the evil twins is illuminating both her face and her understanding, as she attempts to observe them and overhear their conversation. Whereas Dickens is deliberately vague about the nature of Affery's "dreaming," the illustrator affirms what the reader has begun to suspect, that there are two Flinwinches. Mahoney here is also far more sympathetic to Affery as his rendition of her is neither distorted nor awkward: we are to take her character seriously here, and trust her perception, even if in the illustration she is looking through an open door rather than through "the rusty hinges on the door," as in the text, from her perch at the bottom of the solid staircase, its magnitude and solidity suggested by the oversized newel post.

Affery and Jeremiah Flintwinch in the original serial, Diamond, earlier "Household," and Charles Dickens Library Editions, 1856-1910

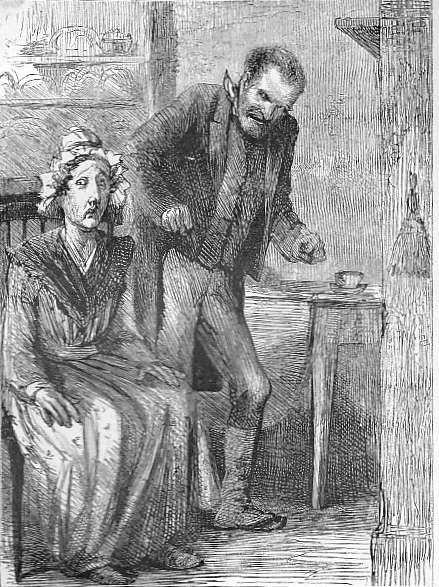

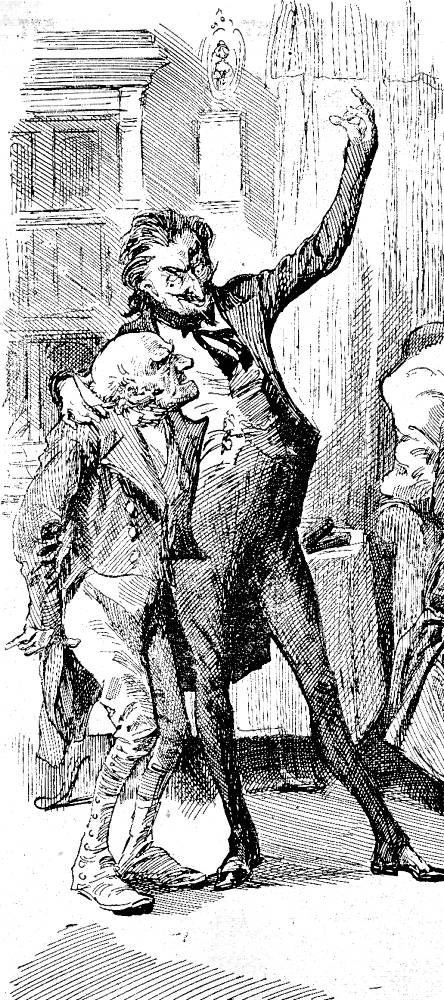

Left: Felix Octavius Carr Darley's frontispiece for the fourth volume of the novel, Closing In — Book II, Chapter XXX. Centre: Sol Eytinge, Junior's study of the anxious Affery and her calculating husband, Mr. and Mrs. Flintwinch (1867). Right: a detail of the English and French villains, short Flintwinch and tall Blandois, Mrs. Clennam and the Plotters — left half of the 1910 lithograph. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: Phiz's study of the original odd-couple, the hectoring, irascible Jeremiah and the constantly apprehensive Affery, Mr.and Mrs. Flintwinch (Book 1, Chapter 15; Part 5, April 1856). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1868 volume, based on the 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 28 May 2016