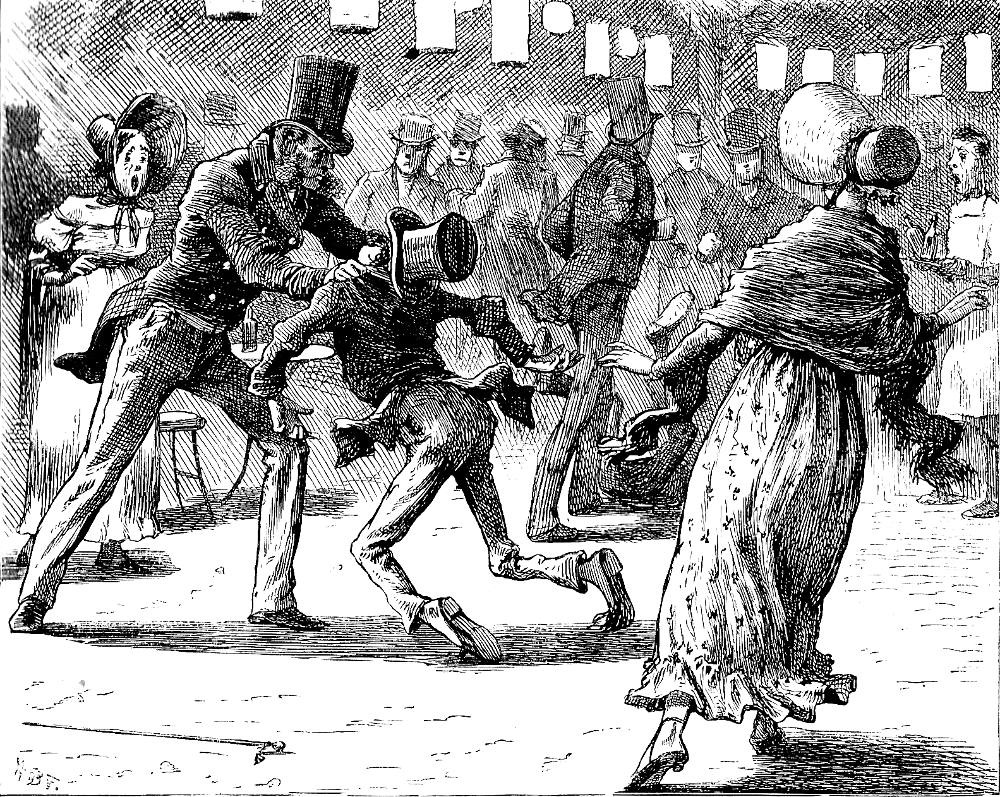

"Horfficer!" screamed the ladies by A. B. Frost, in Charles Dickens's Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day People and Every-day Life, Pictures from Italy, and American Notes (1877), III. "Characters," Chapter IV: "Miss Evans and The Eagle," p. 177. Wood-engraving, 4 ⅛ by 5 ¼ inches (10.5 cm high by 13.3 cm wide), framed. Whereas George Cruikshank in the original anthology merely used the illustrations Miss Jemima Evans (1839) to introduce the principal characters, Miss Jemima Evans and her beau, the illustrators of the Household Edition, Barnard and Frost, have taken this opportunity to depict young Wilkins' confronting the bully at the dance-hall. However, Frost's treatment is far more dynamic than Barnard's, focussing not upon the characters but on the action which makes the diminutive Wilkins look like an oversized rag-doll. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliographical Information

Originally published as "Scenes and Characters No. 2" in Bell's Life in London for 4 October 1835, this early Dickens sketch approaches the condition of a short story with exposition, rising action, and climax. The Second Series contains the original Cruikshank illustration (see below) Miss Jemima Evans, which the artist had to re-engrave for the 1839 Chapman and Hall edition. The 1876 and 1877 Household Editions of Dickens's Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People contain only a single wood-engraving, namely the scene of the altercation at The Eagle.

Passage Illustrated: Wilkins squares off against The Waistcoat and The Whiskers

At length, not satisfied with these numerous atrocities, they actually came up and asked Miss J’mima Ivins, and Miss J’mima Ivins’s friend, to dance, without taking no more notice of Mr. Samuel Wilkins, and Miss J’mima Ivins’s friend’s young man, than if they was nobody!

"What do you mean by that, scoundrel!" exclaimed Mr. Samuel Wilkins, grasping the gilt-knobbed dress-cane firmly in his right hand. "What’s the matter with you, you little humbug?" replied the whiskers. "How dare you insult me and my friend?" inquired the friend’s young man. "You and your friend be hanged!" responded the waistcoat. "Take that," exclaimed Mr. Samuel Wilkins. The ferrule of the gilt-knobbed dress-cane was visible for an instant, and then the light of the variegated lamps shone brightly upon it as it whirled into the air, cane and all. "Give it him," said the waistcoat. "Horficer!" screamed the ladies. Miss J’mima Ivins’s beau, and the friend’s young man, lay gasping on the gravel, and the waistcoat and whiskers were seen no more. [III. "Characters," Chapter IV: "Miss Evans and The Eagle," p. 178]

Commentary

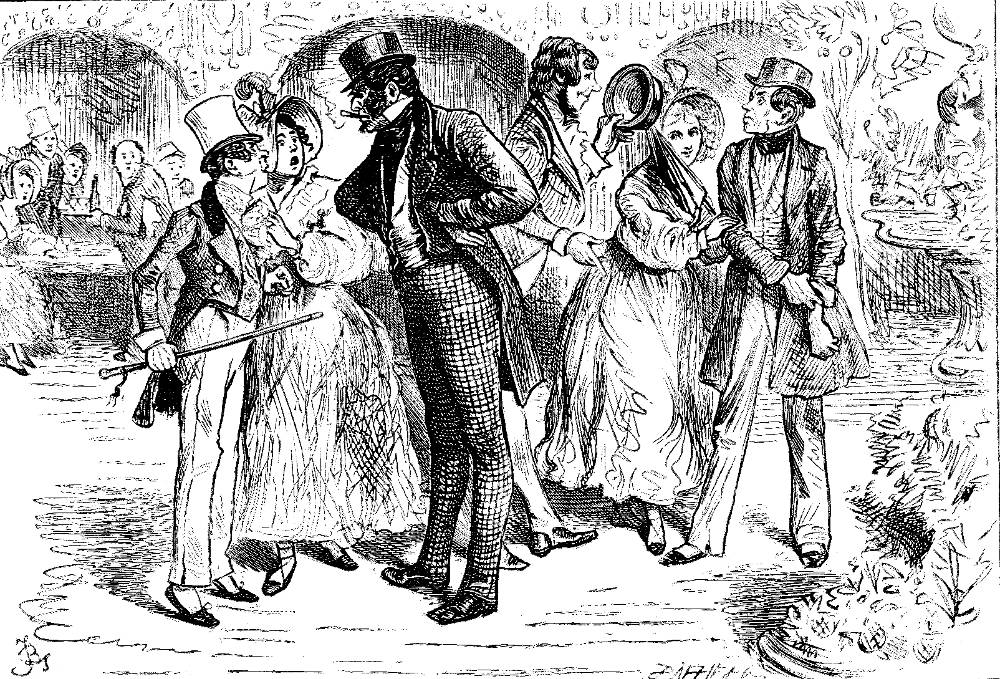

The only precedent that the Household Edition illustrators Barnard and Frost had, George Cruikshank's Miss Jemima Evans (1836), proved of little use since both realistic artists of the 1870s much preferred dynanmic to static scenes. Both, in fact, move directly to the climactic confrontation between The Whiskers and Samuel Wilkins. Now Chapter 4 in "Characters," the sketch (true to its genre) does not develop character much beyond the surface, but finishes upon a point of conflict in a day typical of the life of the titular protagonist and of her class, denizens of Camden Town, a suburb several miles north of The City familiar to Dickens from youth. Since the sketch is as much a verbal portrait as a tale, the reader can appreciate George Cruikshank's strategy of merely describing the young couple as they appear at the outset — Samuel Wilkins, dressed for an evening out, and Jemima Evans in her white muslin dress that shows her shoulders to advantage. Frost, unlike Barnard, has chosen to retain the details of the muslin dress worm by Jemima Evans in the original illustration, and positioned upper left in the Frost; both later illustrators have retained the large straw bonnet to humorous effect. However, whereas Barnard sets the scene up as if it were on stage, Frost draws the eye of the viewer to the central figures, the gigantic but fashionably-dressed Whiskers as he vigorously shakes his adversary. Frost captures the very moment in which little Wilkins is about to lose his hat as the other figures in the dance-hall view the assault beneath the decorative lanterns with shock and revulsion. In the middle of the scene, Frost has placed the masher's companion, who has taken an agressive stance, and apparently knocked to the ground the hapless boyfriend who has accompanied Jemima's friend to the tavern, although all wer can see of him is a foot in the air.

Having consumed alcoholic beverages at The Crown previously and now at The Eagle, Samuel Wilkins has called out a man much larger and physically powerful than he to defend his fiancée's honour, to say nothing of his own. Frost focuses on the masher, "Whiskers," as a formidable figure, and relegates his less menacing companion ("plaid waistcoat") to the background; in contrast, he figures prominently in the Barnard version, "What do you mean by that, scoundrel?" exclaimed Mr. Samuel Wilkins, grasping the gilt-knobbed dress cane. Dominating the left-hand register of Frost's composition, the dark, kinetic figure of the masher" in black looms over a diminutive Wilkins, whose tail-coat flares out, as if he were about to fly. Meantime, Jemima's friend, sounds the alarm (right); Frost has her stretch her hands out and puts her figure on a diagonal, as if she is losing her balance, but he leaves the completion of her character, her facial expression, up to the reader to complete. Although Barnard uses the background to give a fragmentary notion of The Eagle itself, with greenery and a fountain (right) and refreshment tables (upper left), Frost merely presents the dozen lanterns and eight respectably-hatted gentlemen in the background. Only through the open-mouthed waiter (extreme right) does Frost suggest the consternation at the eruption of such violence in a social context. Executing this drawing in 1877, after he had probably seen the Barnard illustration, and as yet unfamiliar personally with London scenes and characters, Frost would have known only what Dickens indicates about The Eagle. Barnard, on the other hand, communicates a Londoner's sense of the physical setting; he probably remembered what The Eagle would have looked like before it became the Grecian Theatre in 1858, although evidently the later building retained the original rotunda Bentley et al. note that The Eagle, located at the busy junction of City Road and Shepherdess Walk, Hackney, served as more than a mere public house, for it originated as a tea garden, and then in 1825 was transformed into the music hall which serves as the backdrop for both Household Edition illustrations:

Eagle, the (dem.), famous tavern and pleasure garden in the City Road, east London, a popular resort of the lower middle-class. The rotunda, where the concerts were held, was demolished in 1901 after being turned into the Grecian Theatre. Inside the gardens were 'beautifully gravelled and planted' walks with a 'place for dancing', 'variegated lamps', 'a Moorish band . . . and an opposition military band'. [The Dickens Index, p. 84]

The famous drinking establishment is obliquely commemorated in the children's rhyme "Pop Goes the Weasel": "Up and down the City Road / In and out the Eagle" ("Notable Pubs #1: The Eagle Tavern, London"). An alternative meaning of "Pop Goes the Weasle" involves a middle-class clerk who is down on his luck having to pawn his business attire in order to buy food and drink: in Cockney rhyming slang, "weasel" stands for "coat" and "pop" for "pawn."

As Dickens's sketch on the subject (perhaps based direct experience of the place, although the tea-gardens at Jack Straw's Castle, Hampstead, were his favourite haunt) makes plain, the 19th century British tea-garden was a popular resort on Sunday afternoons. The rejuvenated Eagle, with its grassy walks and fountains (which Frost has sketched in the backdrop of the present illustration) was perhaps one of the few entertainment venues open on a Sunday afternoon as a consequence of the restrictive Lord's Day Act. Going to the gardens involved strolling around ponds and garden statues, and taking light (non-alcoholic) refreshment. Think of the tea-garden which Dickens describes as the Vauxhall or Ranelagh Gardens for the rising middle-classes in the nineteenth century. In Chapter 46 of the Pickwick Papers (August 1837: Part 16), Dickens stages the arrest of the litigious Mrs. Bardell (for not paying her lawyers' fees) while on excursion with her friends in the pleasure gardens at The Spaniards in Hampstead. From 1840, shortly after Dickens wrote this sketch, music and dancing were licensed at several inns with tea-gardens, such as The Bell in Kilburn High Road.

The character of these places have, with the habits of the people, experienced a very considerable change, and tea, formerly the chief article of consumption here, has been supplanted by liquors of a more stimulating character. At some of these, concerts, of an inferior description, are performed; and other attractions are added that generally detain the company, always of a miscellaneous character, till the approach of midnight. The following are the principal in the vicinity of the metropolis: — New Bagnigge Wells, Bayswater; New Bayswater Tea Gardens; Bull and Bush, Hampstead; Camberwell Grove House; Canonbury House, Islington; Chalk Farm, Primrose Hill; Copenhagen House, Holloway Fields; Eel-pie House, or Sluice House, on the New River, near Hornsey: St. Helena Gardens, near the Lower Road, Deptford; Highbury Barn; Hornsey Wood House, the grounds of which include a fine wood and an extensive piece of water; Jack Straw's Castle, Hampstead Heath; Kilburn Wells, Edgeware Road; Mermaid, Hackney; Montpelier, Walworth; Mount Pleasant, Clapton; the Eagle, City Road; the Red House, Battersea Fields; Southampton Arms, Camden Town; Union Gardens, Chelsea; White Conduit House, Islington; and Yorkshire Stingo, Lisson Green. [Mogg's New Picture of London and Visitor's Guide to it Sights, 1844; cited in Jackson]

See also "The Development of Leisure in Britain, 1700-1850:

- The Development of Leisure in Britain, 1700-1850

- The Development of Leisure in Britain after 1850

- Technology and Leisure in Britain after 1850

Parallel Illustrations from Other Editions

Above: Fred Barnard's realistic interpretation of the conflict at the dancehall, "What do you mean by that, scoundrel?" exclaimed Mr. Samuel Wilkins, grasping the gilt-knobbed dress cane. (1876).

Bibliography

""18th & 19th Century Pleasure and Tea Gardens in London." Jane Austen's World. Web. March 1, 2009 by Vic. Accessed 12 April 2019.

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicholas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens: Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Part One, "Dickens and His Early Illustrators: 1. George Cruikshank. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z. The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1846.

Dickens, Charles. "London Recreations," Chapter 9 in "Scenes," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 67-71.

Dickens, Charles. "London Recreations," Chapter 9 in "Scenes," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Pp. 43-45.

Dickens, Charles. "London Recreations," Chapter 9 in "Scenes," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. I, 86-91.

Dickens, Charles. "Miss Evans and The Eagle," Chapter 4 in "Characters," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 170-74.

Dickens, Charles. "Miss Evans and The Eagle," "Characters," Chapter 4, Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875 [rpt. of 1867 Ticknor & Fields edition]. Pp. 353-55.

Dickens, Charles. "Miss Evans and The Eagle," Chapter IV in "Characters," Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day People and Every-day Life, Pictures from Italy, and American Notes. Illustrated by A. B. Frost and Thomas Nast. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1877. Pp. 176-78.

Dickens, Charles. "Miss Evans and The Eagle," Chapter 4 in "Characters," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Pp. 108-10.

Dickens, Charles. "Miss Evans and The Eagle," Chapter 4 in "Characters," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. I, 219-23.

Hawksley, Lucinda Dickens. Chapter 3, "Sketches by Boz." Dickens Bicentenary 1812-2012: Charles Dickens. San Rafael, California: Insight, 2011. Pp. 12-15.

Jackson, Lee. Victorian London - Entertainment and Recreation - Gardens - Tea Gardens." Dirty Old London. New Haven: Yale UP, 2014. Web. Accessed 11 April 2019.

Meaning and interpretations." "Pop Goes the Weasel," Wikipedia. Web. Accessed 11 April 2019.

"Notable Pubs #1: The Eagle Tavern, London." Boak and Bailey's Beer Blog. Web. Accessed 11 April 2019.

Schlicke, Paul. "Sketches by Boz." Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999. Pp. 530-35.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Last modified 12 April 2019