Author and artist visited the Tower each month to study carefully the scene for the next instalment, and then dined convivially together at Ainsworth's house. It was this arrangement, whereby text and illustrations were produced separately, after discussion, that gave Cruikshank an excuse for exaggerating the nature and importance of his own share in the work. [McLean, p. 31]

Throughout much of 1840, William Harrison Ainsworth was working simultaneously on the serial versions of The Tower of London and Guy Fawkes while planning the inaugural number of Ainsworth's Magazine. Ainsworth published both novels beginning in January 1840 in monthly instalments (thirteen parts). He then published The Tower of London in volume form simultaneously with the appearance of the thirteenth and final instalment in the December 1840 number, while Guy Fawkes continued its serial run until November 1841. Ainsworth celebrated the conclusion of the serial and volume forms of The Tower of London with a grand banquet near the offices of his printers, Bradbury and Evans, at the Sussex Hotel.

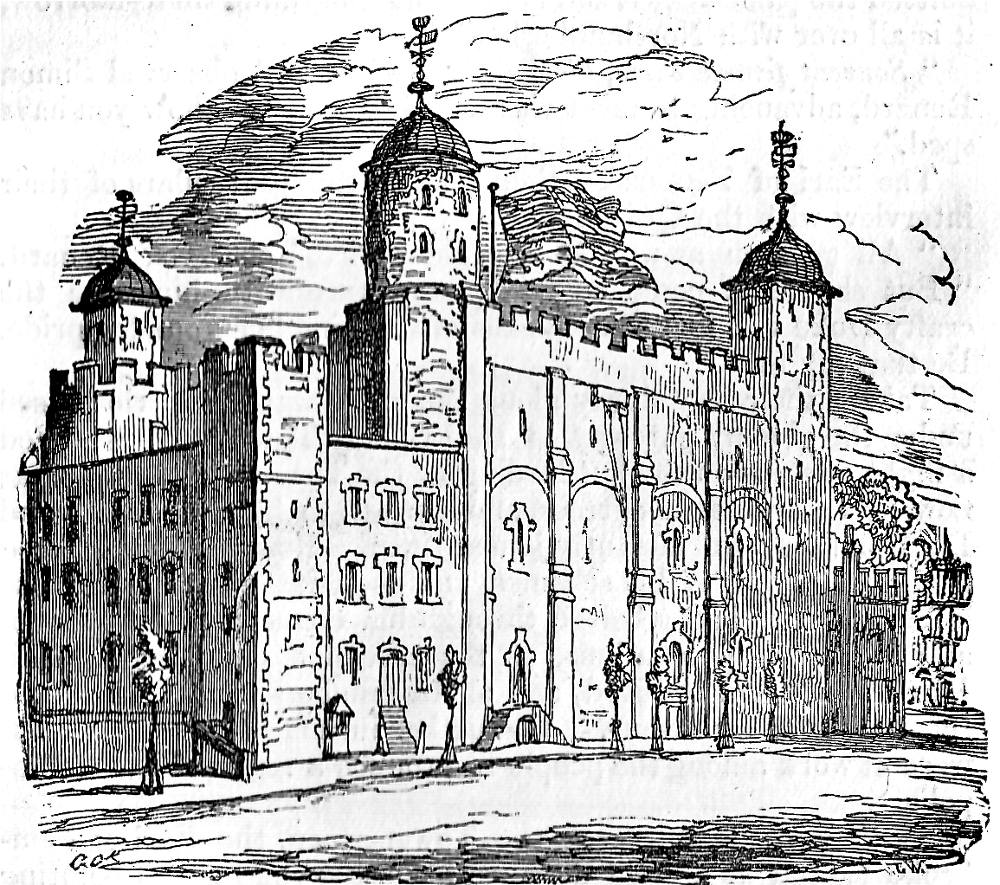

Over the many months of writing these historical pot-boilers, Ainsworth would often walk through the Tower of London with his illustrator, George Cruikshank, and then return to Kensal Lodge for a discussion of the day's research. This arrangement later led Cruikshank to claim authorship over The Tower of London, which, emulating Scott's Kenilworth, covers the period of July 1553 through February 1554, and therefore required the kind of historical research which Ainsworth had conducted for Jack Sheppard, studying London in an earlier era. Cruikshank did not need to conduct such research for his illustrations since he had the actual architecture of The Tower of London, somewhat changed since the seventeenth century, before him whenever he needed it. Although he found that his tendencies towards situational comedy and caricature had little opportunity for expression in Ainsworth's historical novel, his penchant for the grotesque is highly effective in his illustration of the death of the melodramatic villain Lawrence Nightgall, Keeper of the Tower. The illustration when combined with Ainsworth's vivid description satisfied the contemporary taste for a neat closure with poetic justice.

Routinely over the first days of a month the partners would meet at the Tower, and explore those regions in which the next instalment's action would be set. They would then go their separate ways: Ainsworth to his library at Kensal Green to consult historical sources and draft the text of the next number; Cruikshank back to the Tower repeatedly to draft sketches for the wood-engravers. In his studio, the illustrator created the tracings needed to etch the steels, which he would then dispatch to Ainsworth for any last-minute instructions about details depicted in the action drawings, which were necessarily the subject of many of the extant thirty-three letters between the two that survive from these months of 1840. According to Robert L. Patten, Cruikshank either produced or tightened up many of the titles of the steels.

The minute particulars of the Tower's architecture and history were obsessively researched by both Ainsworth and Cruikshank. As the author constructed a parallel narrative of romance and antiquarian detail, the artist produced forty atmospheric engravings of events in the story and a further fifty-eight woodcuts devoted to purely architectural features, while both pestered The Governor of the Tower and the Keeper of the Regalia to visit areas that were then closed to the public while researching. As always, the author has excelled at hybridisation. Fact and fiction are skilfully blended here, resulting in a cohesive whole so complete in detail that its reputation as an authority on the history of the Tower endured as late as the 1950s. The Tower of London is also one of the few novels to be equipped with a full index. When Ainsworth began this project, the Tower was an abandoned garrison, closed in most part to the public and mutilated by modern alteration in some areas while practically falling down in others, but as the romance progressed thousands of people visited the monument to trace the places and events depicted by Ainsworth’s pen and Cruikshank's pencil. Demolition ceased due to renewed public interest, and the Tower was restored, both as one of the first Victorian museums and as a patriotic symbol in the national psyche. The novel was therefore extravagantly dedicated to Queen Victoria. The Tower of London set the standard for Ainsworth's history of England. Forty years on he was still turning national landmarks into gothic castles and populating them with fated monarchs, paupers of noble birth, gothic villains and gory ghosts. [Stephen Carver, "Ainsworth & Friends."]

The fifty-eight wood-engravings of the environs of the Tower of London and the forty etchings of scenes in The Tower of London. A Historical Romance represent the acme of the Cruikshank-Ainsworth five-year artistic collaboration. However, just a year later, the relationship between the literary heir to the mantle of historical novelist Sir Walter Scott and the redoubtable illustrator of Oliver Twist suffered a rupture. Ainsworth and Cruikshank enjoyed a productive artistic collaboration across eight novels, although there was a temporary rift in 1841. Having developed jointly notions for Old St. Paul's, A Tale Of The Plague And The Fire (1841) with Cruikshank, who designed the monthly wrapper, Ainsworth then elected to have its monthly serial parts illustrated by John Franklin instead. The partnership between Cruikshank and Ainsworth began with the rogue novel Jack Sheppard in 1839 lasted until 1845:

Cruikshank did not illustrate Old St. Paul's (which came out in monthly parts in 1841), but rejoined Ainsworth when the latter, having resigned the editorship of Bentley's Miscellany in 1841, started his own miscellany, Ainsworth's Magazine (Cohn 22), of which the first number appeared in February 1842. In this Cruikshank illustrated The Miser's Daughter (February to November 1842), Windsor Castle (July 1842 to June 1843; the first few parts were illustrated by [French graphic artist] Tony Johannot) and St. James's, or the Court of QueenAnne (January to December 1844). [Burton, p. 1-9]

However, the 1840 novel is not merely a monument to a highly productive partnership:

Ainsworth's The Tower of London is the first successful English exploitation of London topography along the lines of Eugène Sue's Mysteries of Paris and, pre-eminently, Victor Hugo's Notre Dame de Paris. [Sutherland, p. 633]

Of the eight Ainsworth novels upon which Cruikshank worked in the late 1830s and early 1840s, with a total production of 218 plates on steel and wood, nearly half occur in the lengthy program of forty etchings and fifty-eight wood-engravings that he designed for the twelve-part serialisation of The Tower of London.

The technical excellence of the best of these plates in their fidelity to historical detail suggests that during these years [working with Ainsworth, 1836-41] Cruikshank had adopted an altogether more ambitious view if the illustrators's role. He shared Ainsworth's concern for minute accuracy in the rendering of architectural setting, period costume, and so forth; and as their correspondence shows, the two conferred at length about such matters and together conducted a good deal of on-the-spot research. In preparing the designs Cruikshank clearly found some measure of compensation for the career as an historical painter from which his lack of academic training debarred him. [E. D. H.Johnson, p. 18-19]

Nevertheless, W. H. Chesson and others have criticized Cruikshank's performance in this novel in terms of such matters as the unrealistic darkness of Simon Renard's skin, Lady Jane's impossibly slender waist, and his defective figure-drawing generally. The anonymous reviewer in the Athenaeum pronounced Cruikshank's depiction of the three female principals (Queens Jane, Mary Tudor, and Eklizabeth) as "Mere skeletons in farthingales" (cited in Chesson, p. 82).

Related material

- The 98 Plates

- William Blanchard Jerrold on Cruikshank's illustrations for W. H. Ainsworth's The Tower of London (1840)

- Paintings, drawings, illustrations, and photographs of the Tower of London

- Frank Brangwyn's title-page for Gibbings' two-volume edition (1901)

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank and Frank Brangwyn. The Novels of William Harrison Ainsworth, vol. 3. The Windsor Edition. London: Gibbings; Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott; Edinburgh: Ballantyne and Hanson, July, 1901.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. Accessed 1 October 2017. https://ainsworthandfriends.wordpress.com/2013/01/16/william-harrison-ainsworth-the-life-and-adventures-of-the-lancashire-novelist/

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882)." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Jerrold, William Blanchard. Chapter 9, "Illustrations to Harrison Ainsworth's Romances." The Life of George Cruikshank. New York: Scribner and Welford, 1882. 2 vols. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/44741/44741-h/44741-h.htm

Johnson, E. D. H. "The George Cruikshank Collection at Princeton." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 1-34.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Patten, Robert L. "Phase 3: "Immortal George," 1835–1851." Chapter 29. "The Tower! Is the Word — Forward to the Tower!" George Cruikshank's Life, Times, and Art, vol. 2: 1835-1878. Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers U. P., 1991; London: The Lutterworth Press, 1996. Pp. 129-152.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993. P. 633.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 21 November 2017